Apr 10, 2024

Facing Disproportionate Danger, Rural Communities Take a Grassroots Approach to Road Safety

Country roads take millions of Americans home each day — and are host to a disproportionate number of fatal crashes in the process.

While an estimated 20% of people in the U.S. live in rural areas, 40% of traffic deaths occur on rural roads, according to the most recent data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). In rural areas, the fatality rate per vehicle miles traveled was 1.5 times higher than in urban areas.

Public transportation and walkability are limited in many rural communities, making the people who live there reliant on cars and roads to get around — and making traffic safety especially important. But rural roadways — which tend to have higher speed limits, less lighting, narrower lanes, and more unmarked intersections than city streets — can pose unique environmental challenges to drivers. Research also suggests that rural drivers may engage in some riskier behaviors behind the wheel than their non-rural counterparts: They've historically tended to be less likely to wear seat belts than urban drivers, and studies show higher rates of child restraint misuse in rural locations.

…for most people, there's not much more dangerous that they're going to do in a single day.

“When we live in a rural area like this, we're so callous to the amount of time we spend driving, let alone the fact that we're flying down the road at 70-plus miles an hour in an aluminum tube,” said Noel Cooper, Executive Director of Injury Prevention Resources (IPR), a traffic safety nonprofit in Fremont County, Wyoming. “But for most people, there's not much more dangerous that they're going to do in a single day.”

Fundamental Differences

Kevin Elliott, spokesman for the National Center for Rural Road Safety (Safety Center), describes rural communities as “fundamentally different” from urban communities when it comes to traffic safety: “The human beings aren't fundamentally different,” he said, “but their environment is.”

The most common type of crash in rural areas — roadway departures — account for roughly one-third of rural traffic deaths, according to Safety Center data. These crashes include people who leave their lanes and enter another lane, where they may collide with another car, as well as people whose cars go off the road entirely.

“You've got a lot of space [on rural roads] for people to speed and go off the road or out of their lane,” Elliott said.

The design and condition of rural roads themselves can also contribute to risk, Safety Center Director Jamie Sullivan noted in a 2022 webinar hosted by the National Safety Council's Road to Zero Coalition: Rural areas tend to have more unpaved roads, intersections without traffic signals or stop signs, narrower lanes, a lack of shoulders, open ditches near roadways, and less lighting to see by. Speed limits also tend to be higher on rural roads than city streets.

Many rural vehicle accidents involve only one car, while others might involve two or three cars at most; pile-up crashes involving a large number of cars, as often seen on major highways or in cities, are rarer in rural areas, Elliott said.

Collisions involving more than one type of vehicle going vastly different speeds — such as a car and a tractor, horse and buggy, or recreational vehicle like an ATV — are also “some particularly rural types of crashes that you aren't going to see in urban areas,” Elliott added. “If you're somewhere hilly and you're hauling over that hill and there's a combine just on the other side, that's a problem.”

If a problem does arise, it may take longer for help to arrive. Rural EMS agencies often cover much broader swaths of land than urban agencies, leading to significantly longer response times.

Buckling Up

In the event of a crash, proper seat belt use can be the difference between life and death, or minor and severe injury. Roughly half of all people killed in car crashes in 2021 were unrestrained, according to NHTSA data.

While research shows that seat belt use has historically been lower among rural drivers than non-rural drivers — one study based on data from 2014 found a self-reported seat belt use rate of about 75% in rural counties, compared to about 89% in urban counties — more recent data suggests this may be changing. A 2021 national daytime observational survey showed similar rates of about 90% among front-seat passengers traveling in rural and urban areas.

Another study published in 2021, however, found that rural drivers were more likely to have an unfavorable attitude toward seat belt use, and that drivers who held these negative beliefs were less likely to consistently wear their seat belt. The study's authors concluded that rural drivers “should be treated as a distinct market segment for seat belt messaging and public awareness campaigns,” and that changing rural drivers' beliefs about seat belts “may help reduce the disparity between rural and urban traffic fatality rates.”

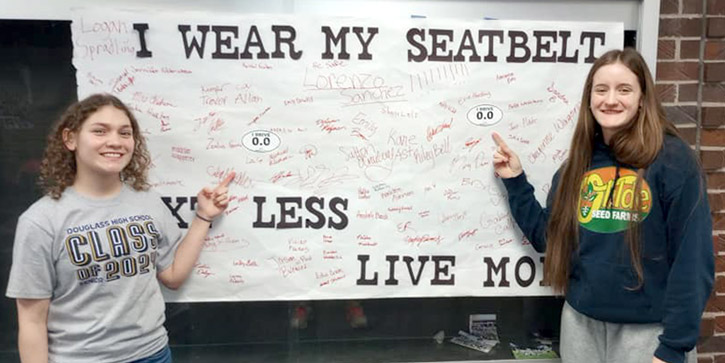

Grassroots community-led programs may be more effective at encouraging seat belt use in rural areas than national or government-led campaigns, experts suggest. One such program, the Seatbelts Are For Everyone (SAFE) program, formed in rural Crawford County, Kansas, in 2008. At the time, Crawford County had one of the lowest rates of seat belt use among teen drivers in the state.

To encourage young people — and, by extension, the adults in their lives — to buckle up, the Crawford County Sheriff's Office teamed up with local high school students, teachers, and community members to create the multi-pronged SAFE program, with seat belt surveys conducted by students at the beginning and end of the school year and a student-led campaign — which includes public messaging, educational events, guest speakers, visible enforcement, and prizes — taking place throughout the year. The SAFE program has since expanded into more than 170 schools across Kansas, a number of which are also rural, as well as schools in Oklahoma and Iowa.

In its first year, one of the six Crawford County high schools that piloted the program went from a 57% seat belt compliance rate to an 82% compliance rate, according to the beginning-of-year and end-of-year surveys. Across all the schools that participated in 2008, there was an average 16 percentage point increase.

“The goal was to build up recognition of the importance of wearing your seat belt, but it also gave the teens in that area a sense of empowerment,” said Chase Hobart, who oversees SAFE in Kansas. “The program is designed to empower them to make smart choices, and then they go home and educate their own families.”

Other rural schools that have since adopted the program have reported similar numbers. Typically, rural schools start with a lower baseline for seat belt use than non-rural schools, Hobart said.

“There's a mentality [in rural Kansas communities] where people think less traffic means less risk of getting into a crash,” Hobart said. “Then you've got the generation that grew up without seat belts or seat belt laws, and they get into a mindset of, ‘Well, I don't need to wear my seat belt. I grew up and I'm just fine.’ And of course, teen drivers specifically, whether rural or not, have that invincibility syndrome where they think that nothing bad can happen to them.”

Many of the teens who participate in the program have personal reasons for doing so, Hobart said, whether they've been in a crash themselves or have lost a loved one. At one school, a former SAFE student lost her own life in a car crash, leading her classmates to campaign for better signage and a public awareness campaign in their community.

“We hate hearing about the tragedies, but if there's anything beautiful that can come from something so horrendous, it's that,” Hobart said. “These kids are a lot more influential than us adults give them credit for.”

Car Seat Safety

For very young children, seat belts aren't enough: Proper car seat or booster seat use is crucial to preventing serious injury or death in a crash. Car seat use can reduce injury risk by between 70 and 80% compared to seat belt use alone, and booster seat use reduces serious injury risk for slightly older children by 45%.

Like rural adults, rural children are also less likely to be properly restrained than their non-rural peers. One study found that child restraint misuse was more common in rural locations, with 9 out of 10 children buckled in insufficiently or not at all.

Safe Start, a nonprofit based out of Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, is aiming to change those statistics locally with its Rural Education Outreach (REO) program. The REO program, which officially launched in 2021, brings a mobile safety lab to rural communities in northern Idaho and western Washington to conduct car seat checks and promote car seat education.

The 24 rural and tribal communities served by the program are all a significant distance from the nearest place to buy a car seat and typically even farther from the nearest place offering car seat installation or education, said Liz Montgomery and Brian Rauscher, who serve as Executive Director and Director of Operations for Safe Start, respectively. Community members often don't have the time or resources to travel and may not be able to afford to purchase a new car seat even if they could make the drive. As a result, Montgomery and Rauscher say they often see car seats that are old, improperly sized, or used incorrectly.

“Not many people know that using a used car seat that you don't know where it came from is dangerous,” Montgomery said. “People don't really understand expiration dates and why car seats expire. And oftentimes they're too small, so the child is over the weight limit for that car seat.”

Using a trailer donated by the national organization Buckle Up for Life, the REO team visits each of the 24 communities twice a year, setting up shop in a public space where anybody can approach for a car seat check, a demonstration, or to have their questions answered. In some cases, the REO team has distributed new car seats to people when needed and has taken old or unsafe seats to dispose of.

At the team's first REO event, Rauscher recalls, they served a 17-year-old expectant mother. The teenager was “terrified,” Rauscher said, and overwhelmed at the prospect of preparing for motherhood while finishing school and living on her own. An hour later, the girl “left with a brand-new car seat and the knowledge to install it, and she gave us the biggest hugs we've ever gotten.”

To promote and organize their events, Safe Start partners with local organizations in each of the rural communities it serves; volunteers from the community also help to staff the car seat checks.

Building trust with each community is incredibly important in reaching families.

“Building trust with each community is incredibly important in reaching families,” Montgomery said. “When they see the local fire department logo on the event posters, they realize we are partnering with a trusted agency, and they are much more likely to stop by.”

Ultimately, Montgomery and Rauscher said, they hope to hand off the events to these local organizations — which include Head Starts, tribal authorities, hospitals, and fire departments — entirely.

“Our goal is to serve these communities for the next few years and then train new local partners that can really take this on and be a local resource,” Rauscher said. “So really what we're trying to do is take these communities where you had very little, if any, access to any kind of car seat education, and create and cultivate local safety experts who can serve their own communities.”

Under the Influence

Across both urban and rural demographics, about one-third of all traffic deaths involve alcohol impairment. While driving under the influence is by no means a uniquely rural occurrence, some uniquely rural factors may contribute to someone's decision to drink and drive in a rural area, said Kaylin Greene, PhD, an associate professor of sociology at Montana State University who has studied rural drinking and driving patterns.

Even though we think about driving after substance use as being an individual problem, it shouldn't be thought of as an individual issue at all.

“Even though we think about driving after substance use as being an individual problem, it shouldn't be thought of as an individual issue at all,” Greene said. “It's influenced by all sorts of things, including community norms, excessive drinking at community events, family, socialization, and the visibility of drinking and driving.”

In Montana, where Greene lives and works, a disproportionately large share of fatal crashes — more than 40% — involve alcohol impairment. In her research examining why young people choose to drive after drinking in Montana, Greene found that influencing factors included social pressure from peers and rural values of independence and self-control.

“Rural people are fiercely independent: They want to drive themselves and they don't want to be dependent on anybody else, even if it's a friend,” Greene said. “And this is made way worse by the intersection of cultural factors with environmental factors. If you're in a town or city, there might be public transportation, or you could walk. And even if your friend drove you, they wouldn't have to drive that far. But if you live 20 miles from the bar, it's just too big of an ask.”

Young people surveyed in the study also tended to share “a perception that it was very unlikely that they would get caught,” Greene noted. “There were young people who thought, ‘There's one sheriff in this whole county, and we know where that sheriff lives and where they patrol, so there's no concern.’”

A Community Approach

In neighboring Wyoming, IPR is taking a community-centered approach to combating impaired and distracted driving from its home base in rural Fremont County. With the support of the Wyoming Department of Transportation's Highway Safety office, the nonprofit has implemented several grassroots initiatives to build on state-level public awareness efforts.

“It's very, very important to be able to have a person in front of you having those conversations with you, your family, and your kids to reinforce messages from state-level campaigns,” Cooper said. “We hope to help break through that barrier of just seeing another billboard or hearing another radio ad.”

IPR's #RoadWarriors program recruits community volunteers to hold public events encouraging seat belt use and educating people on the dangers of impaired and distracted driving, while also promoting traffic safety through social media messaging. The program uses county data on local traffic fatalities to, quite literally, drive its point home.

“Most people are going to have a connection to [at least one of the crashes], whether it happened right near their home, or it was a family member or friend,” Cooper said. “People can see and understand, ‘Wow, all these crashes occurred right here in our backyard, right in our own home.’ When you ask a room full of people how many of them have been in a crash or been impacted by one, you start to realize how widespread the issue really is.”

IPR's Adult Alcohol Education program, which is primarily aimed at people who have been convicted of driving under the influence, takes a similar face-to-face approach. A panel of local people whose lives have been affected by impaired drivers share their stories with an audience of court-ordered offenders and any members of the public who want to attend. While the focus of these panels is impaired driving, topics such as seat belt use and distracted driving have been incorporated as well.

“It's big in rural areas that they know that somebody in the community, a familiar face, is linked to this,” Cooper said. “You have that person in front of you, and it's just undeniable when you get to have those real conversations with people. The goal is to either change a behavior in that moment or just to plant a seed that they can take with them that will hopefully grow as they live in our communities.”