Dec 13, 2023

Housing Shortages Are Making Recruitment and Retention Even More Challenging for Some Rural Healthcare Providers

In late 2021, as the most chaotic, early stages of the pandemic receded and vaccines proliferated, Jennifer Riley was looking forward to a return to some semblance of normalcy at Memorial Regional Health in Craig, a small town of around 9,000 in northwest Colorado. After over 10 years with the organization, she had recently been appointed CEO, and recruitment was at the top of her list of priorities. However, as Riley and her staff worked to attract new providers to their 25-bed Critical Access Hospital and affiliated clinics, they began to feel the acute effects of another crisis impacting communities across the country — one for which there is no quick, easy, widely-available solution: a severe local housing shortage.

“We had a lot of travelers [during the pandemic],” said Riley. “We were finally sourcing permanent employees, but we'd make an offer and they'd either be looking for housing on the internet or they'd come out and not find anything — and they'd have to rescind their acceptance.”

Riley recalled a long list of promising candidates lost to the housing crunch: physicians, lab techs, nurses, ENTs. “It just goes on and on,” she said. “I would say it's probably coming up [in the hiring process] one to two times a month.”

Candidates who do accept positions are often forced to make do with imperfect living arrangements. Memorial's chief nursing officer and a former maintenance director both lived out of their campers for the better part of a year while they searched for a suitable place to live. A physician assistant is currently living in a camper south of town. Others become impatient with such precarity: a “really fantastic” physical therapist recruited from out of state recently left town after nine months of unsuccessful house hunting.

According to Craig City Manager Peter Brixius, the local shortage runs the gamut from low-income rentals to middle- and even upper-income single-family homes. Until recently, he said, there had been no major development in Craig since the 1980s. Then, during the pandemic, the migration of urban remote workers to nearby resort towns like Steamboat Springs — paired with a boom in the short-term rental (for example, Airbnb) market — created ripple effects that raised prices even in less-touristed, farther-flung communities like Craig.

The same challenges Riley is facing at the hospital are shared by employers across the community: the school district, the business sector, and the City of Craig itself. Brixius, who is working closely with Riley and others to address the shortage, understands the issue on a personal level. “I just bought a house recently, but I've been here for five years looking for a home that I felt fit our needs,” he said. “It's been a problem for a long time, but the pandemic exacerbated the problem beyond anything we could have imagined.”

Every single hospital that I know of is in a community where there are housing needs.

Though it's little consolation, at least Riley and Brixius know they are not alone. “Every single hospital that I know of is in a community where there are housing needs,” said Riley. “They are struggling with how to make housing available for their workforce — and Colorado, I'm certain, is not unique.”

Many stories have emerged recently of hospitals and other employers across the country building their own employee housing to address local shortages. But such arrangements have their pitfalls and complexities, and most rural healthcare providers — already short on cash and staff — lack the resources to reinvent themselves as landlords and housing development firms. Instead, some are forging creative partnerships to chip away at the issue while they wait for more comprehensive, policy-level solutions to emerge.

Such is the case in Craig. Back in 2021, after relocating across town and demolishing their original 1950 hospital building, the Memorial Regional Health Board of Trustees began exploring housing possibilities for the newly vacant land. Initially, a few developers expressed interest in purchasing the land for a housing project. But the size of the parcel and the cost of the project were prohibitive, and the developers soon lost interest.

Meanwhile, the City of Craig had recently formed a municipal housing authority on the recommendation of a local housing assessment. Eventually, after much discussion, the Memorial Board moved to donate their land to the new Craig Housing Authority, which was able to leverage the donation to secure several million dollars in state and federal grant funding.

Since the deed was officially transferred in January 2023, the project has progressed rapidly: a complex of 20 two- and three-bedroom townhomes is expected to be completed by mid-summer. The homes will be available for purchase by households making up to 120% of the area median income (AMI), with five units initially reserved for employees of Memorial Regional Health. The units must be the owner's primary residence and may not be used as a short- or long-term rental property; additionally, the units “will likely have a limit on upward appreciation” as “future buyers will need to be income qualified,” according to a statement from the Craig Housing Authority. In other words: “The units will remain affordable,” said Brixius.

“Taking Stock” of Rural Housing

A phrase often repeated in rural policy circles — “if you've seen one rural community, you've seen one rural community” — holds especially true in relation to rural housing markets. While it is possible to speak broadly of national trends, “there are a lot of market dynamics that are very different regionally,” said Lance George, Director of Research at the Housing Assistance Council (HAC), a D.C.-based nonprofit that supports affordable rural development.

For instance, according to Taking Stock — a high-level overview of the latest rural housing data published by HAC in October — between 2010 and 2020 “states in the West saw the highest rates of rural housing growth while those in the Midwest, Southeast, and industrial North witnessed paltry growth or declines in their occupied rural housing stock.” Whatever new development took place in the rural West, however, was outpaced in many communities by population gains.

Regional vacancy rates — and their causes — also vary widely. Taking Stock notes that approximately 20% of rural housing units are vacant, compared to 11% nationally. So, what rural housing shortage? The report goes on: “Much of the vacancy rate in rural areas is due to the number of homes unoccupied for seasonal, recreational, or occasional use. Often referred to as ‘vacation homes,’ these units comprise nearly half — 47 percent — of all rural home vacancies.” In some coastal regions and other “amenity rich rural locales,” this percentage may be even higher, leading to very few available units. In other rural areas, a greater number of vacancies may be attributable to severe dilapidation.

There's just a lack of supply that we are seeing increasingly in rural areas, and that was not as much the case before.

Regional variations aside, there is a “fundamental issue around what is being built” in every part of the country, said George — namely, a lack of new affordable rental properties and single-family “starter” homes. According to Freddie Mac, “the share of entry-level homes in overall construction declined from 40% in the early 1980s to around 7% in 2019.” Additionally, Taking Stock notes that federal Section 515 Rural Rental Housing Loan maturities will “remove thousands of affordable apartments from rural America every year” throughout the coming decades. “There's just a lack of supply that we are seeing increasingly in rural areas,” said George, “and that was not as much the case before.”

One barrier to ramping up affordable rural development is that — in the absence of significant public funding and incentives — there is more money to be made in the upper-income urban market. But that is just the tip of the iceberg, according to a policy brief published in October by the University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center. After conversations with 27 housing experts representing organizations across the country, researchers noted:

“…the lack of existing homes is related to the availability of housing for a workforce to build new homes, which can also lead to a lack of services available for building, as well as making repairs to additional housing stock…Additionally, the high cost of building (including supply chain costs) combined with the infrastructure issues (lack of roads, adequate utilities, and broadband) also contribute to challenges for contractors and organizations that may otherwise consider building in a rural community.”

In Craig, the Housing Authority circumvented some of these challenges by purchasing factory-built “modular” homes — a strategy detailed in Taking Stock — which will be transported from a manufacturing plant across the state. Some of the grant funding for the project had to be used within a short timeframe, and “for a local contractor to take on a project of that magnitude within that timeframe, it looked unlikely that that was going to happen without looking at modular construction,” said Brixius. The homes will also meet “high-end energy efficiency challenges that a lot of construction doesn't” for roughly the same cost as a traditional, stick-built home.

Both Brixius and Riley are aware of the additional need for more affordable rental options in Craig. According to Brixius, the Housing Authority has plans for a 96-unit complex in the middle-income price range as well as the renovation of an existing, 120-unit low-income complex. Both developments could help further mitigate housing-related recruitment and retention issues at Memorial Regional Health. After all, essential positions in any health system span a wide range of incomes — from food service workers and custodians to specialists and surgeons.

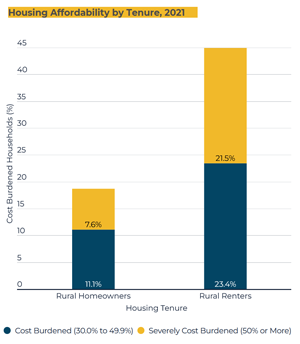

The Housing Assistance Council's decennial Taking Stock report, released in October, highlights the impact of rising housing costs on rural populations. The report notes, “Over 5.6 million — or one quarter of rural households — pay more than 30 percent of their monthly income toward housing costs and are considered cost-burdened. The incidence of housing cost burden has increased markedly for rural households over the past few decades. Housing affordability problems are especially problematic for rural renters.”

A Housing “Experiment,” Driven by Necessity

An innovative project in rural Oregon will soon house an unlikely mix of renters within an equally unlikely building. When it reopens this spring, the former Red Lion Inn & Suites in Seaside will offer 38 market-rate rentals reserved for local healthcare workers in addition to 17 permanent supportive housing units for individuals with behavioral health conditions who have been, or are at high risk for becoming, homeless. The project is led by Columbia Pacific CCO — a coordinated care organization serving northwest Oregon — which will contract with external agencies for property management and housing support services.

According to Columbia Pacific Executive Director Mimi Haley, the housing shortage in northwest Oregon long predates the pandemic era. “It's a very beautiful spot and therefore generates a lot of interest from wealth outside of the community — and that creates a shortage of homes for the workforce, the people who are serving those tourists who like to spend time on the coast,” said Haley. Additional factors contributing to the shortage include a lack of developable land — the region is home to protected state and national forests — and municipal policies that restrict and discourage new development.

In many ways, the resulting recruitment and retention challenges Haley has observed in Seaside closely mirror the challenges in Craig — only worse. For example, an expensive new dental clinic opened in town, but “they could only keep it open four hours a week because they could not find dentists, dental hygienists, and other staff who could find a place to live,” said Haley. In a press release, a local behavioral health provider reported losing “about 30% of the applicants in our job pipeline because of a lack of housing.”

Meanwhile, the per capita rate of homelessness has soared: Clatsop County, where Seaside is located, has the highest rate in Oregon — which has one of the highest rates in the nation. “The need for both kinds of housing [workforce and permanent supportive housing] is just critical,” said Leslie Ford, Columbia Pacific's Housing Strategy and Development Advisor. For several years, she and Haley had been looking for opportunities to address both crises in the Seaside area. When the Red Lion building emerged as a potential project site, they struggled to decide which type of housing to prioritize — so they designed a model that will offer both.

Plus, the Red Lion building “lent itself to this kind of experiment,” said Ford. The building is divided into two distinct sections: the units reserved for healthcare workers are accessible via external stairways and corridors, whereas the permanent supportive housing units have interior entrances. Clatsop Behavioral Health will manage referrals, placement, and 24/7 staffing for the permanent supportive housing units. Columbia Pacific is currently soliciting applicants for a property manager for the healthcare workforce side.

Work is currently underway at the site in preparation for late spring lease-ups. An official groundbreaking ceremony — involving golden sledgehammers “because we're not actually turning the earth” — was held on November 9. Converting the hotel rooms into studio apartments will require the installation of kitchenettes and the addition of walls to section off bedrooms, among other, smaller renovations. Ford estimates that the process will be “half the price of construction and much faster.”

So far, the response from the community has been “overwhelmingly positive,” said Ford. The project “sailed through” the conditional use permitting process, and interest from potential future tenants has been strong. “One of the challenges has been people walking in off the street, wanting to be able to rent an apartment, thinking that it will be available to the general public — and we've actually had to develop some one-pagers that the front desk of the hotel can hand out to let them know the limitations of the units, who they are going to be for,” said Haley.

We had a nurse camping in the woods one year.

As for the two local populations who will qualify for the units, the distinctions are sometimes blurry. “We had a nurse camping in the woods one year,” said Pam Cooper, Director of Finance at Providence Seaside Hospital and Columbia Pacific board member. She suspects there are current staff who are couch surfing. Others are driving long distances to work each day. She hopes a few of the hospital's employees will find a home in the renovated hotel.

“This project is a beautiful example of community partners working together to serve all, especially the poor and vulnerable — which just happens to be the mission of the Sisters of Providence,” said Cooper, referring to the Catholic sisters who founded the first Providence hospitals.

Since 2020, Columbia Pacific has provided funding and support to numerous additional housing initiatives in northwest Oregon — including permanent supportive housing, recovery housing, and affordable housing for seniors. The Red Lion project is their first foray into healthcare workforce housing — but, perhaps, not their last. Columbia Pacific has retained a research organization to conduct a formal evaluation of resident satisfaction and the building's impact on healthcare recruitment and retention. “We can always drop back and do a different model if we need to, but we want to see if this works,” said Ford.

At the groundbreaking in November, Columbia Pacific leadership announced one additional change beyond the interior renovations: the building will be renamed The Hawk's Eye Apartments. “A hawk's eye is a blue gemstone, used for centuries to heal the mind, body, and spirit. And blue is a color that resonates in terms of calmness and stress reduction,” said Haley. “We do think that the name is fitting given what the use of the building will be.”