Jan 11, 2023

'A Life-Changing Partnership': First Tribally-Affiliated Medical School in the U.S. Builds Workforce Pipeline to Underserved Communities

From a young age, Cassie McCoy was keenly aware of two things: her citizenship in the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, and her ambition to work as a doctor someday.

As a child, McCoy watched her grandfather play multiple roles within the Peoria Tribe, an experience that instilled in her the importance of her family's heritage. And when doctors helped her father get back on his feet after congestive heart failure, “bringing him back to being my normal, playful dad,” McCoy saw the impact that medicine had, and knew it was what she wanted to do.

So when she heard that Oklahoma State University (OSU) had partnered with the Cherokee Nation to open the country's first tribally-affiliated medical school in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, applying was an easy decision.

“It was just a perfect fit and a way to really honor my heritage, the Native American community, and my family,” McCoy said.

Now a second-year student at the OSU College of Osteopathic Medicine at the Cherokee Nation (COM-CN), McCoy is one of 159 students who make up the school's first three cohorts. The college, which welcomed its inaugural class in 2020, prepares future doctors to work in rural and tribal settings through a curriculum emphasizing cultural competency and daily immersion in the local community of Tahlequah, the capital city of the Cherokee Nation.

By recruiting rural and indigenous students — two historically underrepresented populations in medical schools — and exposing all of its students to rural medicine and life, the college aims to create a new workforce pipeline to communities where healthcare workers are in short supply. Behind the effort is a first-of-its-kind collaboration that Chuck Hoskin, Jr., Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, describes as a “life-changing partnership.”

Now students can attend medical school, complete their residencies in training, and practice medicine all in the same community.

“Together, Cherokee Nation and OSU are advancing quality healthcare for all by teaching a new generation of medical professionals to serve the healthcare needs of our underserved rural communities and Native populations,” Hoskin said. “Now students can attend medical school, complete their residencies in training, and practice medicine all in the same community.”

'Building Trust and Improving Care'

The 84,000 square foot facility in Tahlequah officially opened its doors in early 2021, following half a year of virtual classes for the college's first cohort of students. The facility itself was paid for by the Cherokee Nation, while OSU staffed the college and provided the educational technology. The school had been nearly a decade in the making, with conversations between OSU and the Cherokee Nation starting in 2012.

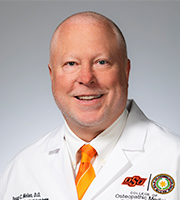

Oklahoma has one of the most severe doctor shortages in the nation, ranking 48th for number of active physicians per capita in 2022. In rural parts of the state, it isn't uncommon for a county to have one primary care provider, said Natasha Bray, DO, Dean of the College of Osteopathic Medicine at the Cherokee Nation. While telehealth has proven to be a helpful tool for some communities, it isn't a reliable alternative for patients who lack access to high-speed internet, Bray said — and isn't a direct substitute for in-person care.

“All people deserve a healthcare provider who's going to be able to be their partner and be present with them,” Bray said. “The development of that relationship is so critical to building trust and improving care in our rural communities.”

Doctors who are already familiar with rural life often find it easier to comfortably live and work in rural communities, making them more likely to stick around those communities for the long run, she added.

“They understand all that is amazing about living in a rural community and they understand what the challenges are,” Bray said. “They're able to successfully build a practice and care for their community, because they have an understanding of what's involved in it.”

Young people from rural and tribal communities who go into medicine often attend medical school and complete their residencies in larger metropolitan areas, where the majority of opportunities are located, noted Douglas Nolan, DO, Associate Dean of Tribal Health Affairs for the college. Nolan, who himself grew up in Tahlequah, returned home after medical school to practice family medicine, later going on to serve as medical director for the Cherokee Nation's W.W. Hastings Hospital in his hometown. But Nolan is something of an outlier among doctors with rural Oklahoman roots.

Once they leave those rural areas, they don't return.

“Once they leave those rural areas, they don't return,” Nolan said. “By putting the medical school here, they're staying in a rural environment, making it easier to recruit them back to the areas they came from.”

For the students at the college who don't come from a rural background, the school's leadership hopes that the small town setting provides positive exposure to rural life — and sparks a newfound interest in rural care.

“Hopefully they fall in love with Tahlequah and see that it is possible to live in a rural community and be happy, and be really effective in the care they provide,” Bray said.

Many of Oklahoma's tribal health systems already stand as “shining examples” for providing wraparound care and services, Bray said. Since 2021, the Cherokee Nation alone has invested upwards of $440 million into projects to improve and grow the tribe's healthcare infrastructure in Oklahoma, including the construction and expansion of facilities and services in rural communities across the state.

“Most of the tribal nations have robust health centers,” Nolan said. “But they're in rural areas, so recruiting physicians can be difficult.”

Weaving In Cultural Competency

Recruiting physicians who are already familiar with the cultural nuances and history of rural and tribal communities — allowing them to build trust and rapport with patients with relative ease — can be doubly difficult.

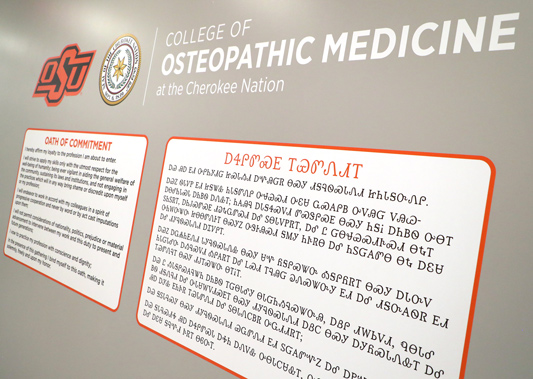

Cultural competency is “woven through everything we do” at the Cherokee Nation campus, according to Bray, from curriculum to training to residency opportunities.

The school shares a curriculum with OSU's College of Osteopathic Medicine in Tulsa, with lecture-based content exchanged between the two locations, and there is some overlap between full-time faculty members on both campuses. But while the two locations share resources, “environment shapes a lot of the learning that happens,” Bray said.

All students at the college take a course on rural healthcare, with an additional course on culture in medicine offered as well. Students also choose between four different tracks when it comes time to train through clinical rotations: a rural track, in which students work in rural communities or Critical Access Hospitals; a tribal track, in which students work in tribal healthcare centers throughout Oklahoma; an urban underserved track, in which students work at Federally Qualified Health Centers in urban environments; and a traditional track, in which students spend most of their time working at larger healthcare centers in Tulsa or Oklahoma City.

Students at the Cherokee Nation campus who don't choose the rural or tribal track will still experience working in a rural or tribal setting at some point during medical school: Each student completes a family medicine clinical rotation with the Cherokee Nation in Tahlequah, and all students must complete at least one rural rotation.

Nolan, in his role as Associate Dean of Tribal Health Affairs, is now working to grow OSU's residency programs in partnership with the Cherokee Nation and other tribal nations. With several family medicine residency programs already established through collaboration with the Cherokee Nation, Choctaw Nation and Chickasaw Nation, Nolan is now in conversation with tribal leaders throughout the state to gauge the need for potential residency opportunities in specialty fields, such as obstetrics and gynecology.

A Sense of Belonging

Of the students currently enrolled at the college, 1 in 5 students are Native American. Roughly half hail from rural Oklahoma.

Those percentages are in stark contrast to other medical schools across the U.S., where less than 5 percent of students come from rural backgrounds; that percentage drops to less than 0.5 percent for rural students from underrepresented racial or ethnic minority groups. Meanwhile, American Indian and Alaska Native students account for less than 1 percent of medical students nationwide.

The white coat ceremony for the school's first class, which included 12 Native American students, was “a particularly proud moment for me as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation,” Hoskin said.

Bray describes students at the Tahlequah campus as generally falling into one of three categories: those who enroll already passionate about working in rural or tribal healthcare, those with an interest in medicine generally, and those who come from a rural or tribal background and feel that the college offers a more comfortable environment than that of a typical medical school.

“When we look at success in medical education, one of the important components for avoiding burnout is your sense of belonging within a community,” Bray said. “Having people who share your mission, your values, and your goals is extremely important — and that translates not only to individual wellbeing, but also to academic success.”

The comfort of a familiar environment may also allow some students to better engage with the curriculum, Bray said, without the distractions of having to learn to navigate a new setting.

“Just driving to get your oil changed in a big city can be quite overwhelming if you grew up in a small community, and they don't have time to worry about those things because they're busy with medical school,” Bray said. “Having the predictability of knowing how to do things in that environment can really support them in their success.”

The school's administration takes an “open door” approach when it comes to communication between students and staff, Nolan said, to ensure that students feel comfortable asking for guidance or support when needed.

“You can be with them and help them through difficult times, and also make sure that they have someone who they can ask questions,” Nolan said. “Because unless they have a family member who has been through it before, many of them are not aware of things like who they need to contact when it comes to rotations, or how they can make themselves the best candidate for getting into a specific residency that they want.”

For McCoy, the supportive environment of the Tahlequah has been a highlight of her medical school experience.

“There is just this natural sense of family, and I think OSU does a really good job of promoting that and creating a culture where we can ask each other for help,” McCoy said. “You just feel that community, that sense of pride and belonging.”

That feeling “radiates into the community” beyond campus as well, she said, recalling that the Tahlequah City Council held a welcome party for her class and distributed gift cards from local restaurants.

“When we go out to dinner, people have said, 'Are you the medical students? We're so happy that you're here!'” McCoy said. “Everyone is just so kind and welcoming.”

Another highlight for McCoy: the nearly 200 pieces of Native American art displayed throughout the facility, from a hand-beaded cane to the statue she passes by each day when she enters the school.

“I think that's something so special, seeing those little pieces of culture in every aspect of your day,” McCoy said. “It just sets the tone for every day.”

Looking To The Future

The OSU COM-CN has had no trouble attracting applicants from the start, with “a lot of interest” from potential students, Nolan said. The school has also begun to offer shadowing opportunities to undergraduate students, something that wasn't possible in the first few years of the COVID-19 pandemic, and holds workshops at small universities across the state to help pre-med students prepare for the medical school application process. Some of these workshops are targeted at underrepresented populations, including Native American students.

But OSU's outreach to future medical students from rural and tribal communities begins much earlier, with programs aimed at children as young as elementary age.

We want a child growing up in a rural Oklahoma town to look around and say, 'I have opportunities to become a doctor, and I can come back and serve this community.'

“We want a child growing up in a rural Oklahoma town to look around and say, 'I have opportunities to become a doctor, and I can come back and serve this community,'” Bray said.

“Teddy bear clinics” held in rural schools teach young students about the importance of seeing the doctor, while other science-based activities — such as learning about forensics through studying fingerprints — aim to make science feel “fun and exciting,” Bray said.

OSU also operates two programs targeting high school students in rural and underserved parts of the state: the Blue Coat to White Coat program, a partnership with the Oklahoma chapter of Future Farmers of America, and Operation Orange, a free one-day camp that travels to six communities across the state to simulate a day in the life of a medical student for middle and high school students interested in working in medicine.

At one Operation Orange camp site last summer, Hoskin welcomed an estimated 75 middle school students to the facility, Nolan recalled, and asked the students to raise their hands if they were Cherokee. Over half of the hands in the room went up.

“To see that many middle school students that are giving up a day of their summer to come learn what it might be like to be a physician, it was encouraging,” Nolan said. “I think you're going to see it pay off in the future.”