Apr 08, 2020

Concussion in Rural America: Experts Detail Injury and Recovery of Traumatic Brain Injury

“After the blood and stitches are gone, you're still living with an injured brain for the rest of your life,” Judy Nichelson said.

Nichelson, who lives in rural North Platte, Nebraska, serves as chair of the Nebraska Brain Injury Advisory Council. As a rural Nebraskan with a traumatic brain injury (TBI) herself, she felt driven to make sure the organization's resources reached the state's rural regions outside of Lincoln and Omaha.

“There are over 77,000

square miles out here with people who have brain

injuries,” she said. “I was a little

noisy and thought it was important to keep advocating for

local resources in the rest of the state.”

“There are over 77,000

square miles out here with people who have brain

injuries,” she said. “I was a little

noisy and thought it was important to keep advocating for

local resources in the rest of the state.”

Nichelson's TBI occurred in 2005 in a car accident when she tried to outmaneuver a vehicle coming towards her head-on. Over the last fifteen years, she said that she's learned a lot about how to maneuver through daily activities with an injured brain. Since she is a registered nurse, one barrier she overcame was the stigma and perception that she had too much education and was therefore “faking it.”

“Of course, I remember a lot from my training, yet sometimes I couldn't remember to take my own pills,” she said. “I was working with a cognitive therapist and distinctly remember the day she looked at me and said, 'You really don't remember, do you?' Getting involved with brain injury resource groups gives me the chance to help others when they face the same issues I have. It's important for people with injured brains to know that, though their life is different, it can still be good when they better understand their symptoms and what can be done to manage their life with these symptoms.”

Nichelson said that she believes support networks have great value in rural areas. Since clinicians are so busy managing acute medical issues that, even if the chronic issues associated with brain-injured patients are recognized, they often have to be set aside due to higher-acuity issues. More often, she said, she thinks the post-injury problems aren't recognized since the majority of clinicians haven't had specific training in brain injuries. She said statewide rural support networks can help bridge these gaps, not only for TBI patients who self-recognize they need assistance, but also in getting the word out to those who might not yet recognize their symptoms are related to TBI. Nichelson said the state's newly formed Nebraska Injured Brain Network currently has three rural areas formally engaged and three additional areas completing their applications. Nichelson is chair of North Platte's chapter.

Brain Injury: Clinical Basics and Severity Categories

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a concussion, or traumatic brain injury (TBI), is defined as a “disruption in the normal function of the brain that can be caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head, or penetrating head injury.”

Because the brain is not rigidly attached to the inside of the skull and instead “floats” around in the skull to some degree, any significant force that causes the head to move quickly in any direction can cause the brain to strike against the skull. Not only do injuries result from a “direct hit” to the head, but from any event that can cause a fast motion in any direction, as seen in this 30-second video:

Researchers also point out that, because the brain is actually a collection of nerves that send signals and make chemicals that control physical and emotional body functions, these injuries can negatively alter those signals and chemical production processes.

|

TBI Severity Criteria |

|||

| Criteria | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Loss of consciousness | < 30 minutes | 30 minutes to 24 hours | >24 hours |

|

Post-traumatic amnesia/memory loss |

0 – 1 day | >1 day to < 7 days | > 7 days |

| Alteration of Consciousness/ Mental State | A moment to 24 hours | >24 hours | >24 hours |

| Radiographic imaging (CT or MRI) | Normal | Normal or abnormal | Normal or abnormal |

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 13 – 15 | 9 – 12 | 3 – 8 |

| Abbreviated Injury Scale | 1 – 2 | 3 | 4 – 6 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Multidisciplinary Postacute Rehabilitation for Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Adults

Experts separate brain injury into three categories: mild, moderate, and severe. The loss of consciousness, along with memory loss, referred to as traumatic amnesia, are two of several indicators that help determine an injury's severity. Typically, for a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), the loss of consciousness will be less than 30 minutes and memory loss for around 24 hours or less. Brain injury can also occur even if there was no loss of consciousness.

Experts said it's also important to know that skull X-rays, which evaluate only bone and not brain tissue, are only needed if a skull fracture is suspected. If actual brain tissue injury is suspected, either a CT scan is performed or — even less often — an MRI is needed, the decision depending on the clinical provider's assessment. However, even moderate or severe brain injury can have a normal scan.

Brain Injuries: The Rural Clinician's Perspective

In its 2018 report to Congress on TBI in children, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) highlighted a 1996 journal article focused on the rural primary care of patients with disabilities. The CDC report stated, “Primary care physicians are more likely to be the single source of care for persons with TBI-related disability in rural areas, and they are unlikely to have received advanced training in the management of a TBI.”

“Nearly 25 years later, sadly, I think that's still true,” Dr. Heith Waddell said.

Waddell, a family medicine physician and fifth-generation member of a Wyoming homestead family, practices in Sundance. As the only full-time physician in Crook County, home to nearly 7,500 people in an area the size of Delaware, he cares for patients with TBI on a regular basis.

“Aside from the usual sports injuries,

head injuries are part of many ranching- and farm-related

accidents when people are working their cattle, getting

bucked off their horses,” he said.

“We're not great about using seatbelts in our

county, so we also see our fair share of brain injuries

from vehicle accidents. Head injuries from slipping on

the ice during winter are also pretty common.”

“Aside from the usual sports injuries,

head injuries are part of many ranching- and farm-related

accidents when people are working their cattle, getting

bucked off their horses,” he said.

“We're not great about using seatbelts in our

county, so we also see our fair share of brain injuries

from vehicle accidents. Head injuries from slipping on

the ice during winter are also pretty common.”

Likely due to his non-traditional medical training pathway, Waddell said he might have TBI management skills other family medicine physicians do not. After research experience in New York City that confirmed his desire to practice medicine and live in a rural area, his research mentor convinced him that rural and remote medicine might best be studied in Australia. Waddell took that advice. Though he also completed a U.S. family medicine residency, he said his training in the Australian system provided many experiences he didn't get here.

Waddell has taken special sports concussion training and familiarized himself with the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines on the topic. While practicing in rural South Dakota in a group of six family physicians, he was the only clinician with formal concussion training. In addition to a training gap, he pointed to another problem: difficulty accessing needed specialty care.

“When I need to talk to a specialist to get some advice, I'm often told, 'Just have them make an appointment,'” Waddell said. “That doesn't help the patient at all in the six to eight weeks it takes to get that appointment.”

Waddell, like many rural physicians who serve their communities in a variety of leadership roles, is also on the local school board. This gives him another perspective on rural TBI issues, both locally and around the region. With the restrictions and requirements for school-based sports activities, he said many schools have relationships with orthopedists who provide athletic trainers who are ultimately in charge of concussion follow-up.

“Though these providers are overseeing return to play, I'm aware of situations with common TBI-linked medical conditions like anxiety, depression, and problems with schoolwork that don't get addressed,” he said. “This is just not the expertise of orthopedists.”

Regarding future educational opportunities for TBI, Waddell shared his preference.

“The best training actually happens when I can ask questions of a TBI expert and they can ask questions of us,” Waddell said, stating that experts could also learn from a site visit to Crook County Medical Services District and see up-close the quality, strengths, and limitations of their organization's medical services.

mTBI: Injury with So Many Consequences

The rural perspectives and needs expressed

by Nichelson and Waddell align with the advocacy

service-related work of the Brain Injury Alliance of Iowa.

June Klein-Bacon, a project manager with the

organization, said it supports people with brain

injuries, family members, caregivers, and any individual

or group that has a focus on brain injuries. Its core

service is referred to as “neuro

resource facilitation,” a no-fee service

providing assistance for navigating not just the medical

challenges that arise after a brain injury, but also

challenges in the activities of daily living. For

example, the organization offers support in coping with

the brain injury, connecting individuals and families to

available services and supports, as well as assisting

with transition back into the workforce.

The rural perspectives and needs expressed

by Nichelson and Waddell align with the advocacy

service-related work of the Brain Injury Alliance of Iowa.

June Klein-Bacon, a project manager with the

organization, said it supports people with brain

injuries, family members, caregivers, and any individual

or group that has a focus on brain injuries. Its core

service is referred to as “neuro

resource facilitation,” a no-fee service

providing assistance for navigating not just the medical

challenges that arise after a brain injury, but also

challenges in the activities of daily living. For

example, the organization offers support in coping with

the brain injury, connecting individuals and families to

available services and supports, as well as assisting

with transition back into the workforce.

“We know that there are 95,000 to 100,000 Iowans with long-term disability due to brain injury,” she said. “Yet in terms of rurality, we don't have clear data that tell us where they're living or how they were injured. This would also be very helpful, especially in terms of our injury prevention work.”

From her work around the state, she said she has growing concern about the true numbers of the state's rural citizens with brain injury.

“When considering the rural ethos around mild injuries — that rural toughness that we see and attitude of 'I'll go to the doctor when the work's done' — we also understand the likelihood that many concussions are going undiagnosed,” she said.

Rurality aside, Klein-Bacon brought up additional issues.

“Fifty percent of people who experience brain injury also experience depression,” she said. “Additionally, the CDC tells us that anywhere between 25% and 87% of people who experience incarceration also experienced a traumatic brain injury prior to the incarceration. Not only is that fact sometimes a missing history element when caring for incarcerated individuals, we've learned it's sometimes an important part of understanding a patient's mental illness and other conditions like depression and substance misuse.”

Klein-Bacon shared that the importance around this “missing history” element is prompting her organization to promote brain injury screening, an activity she said more and more state brain injury groups are advocating.

“Screening is not something that a treating clinician needs to do,” she said. “It can be done by the nurse or medical assistant who's doing the appointment intake.”

From her work in rural Iowa, she said one important message concerning concussions, also known as “mild TBI” or mTBI, is that they are by far the most common of brain injuries, in contrast to moderate or severe brain injury. Other experts noted this fact has additional financial consequences as reported in a 2015 public health journal study looking at pediatric brain injury costs: “at the population level, the health care costs after mild TBI far exceeded those of moderate and severe TBI…This was simply a product of the extremely high population burden of mild TBI.”

Klein-Bacon went on to further explain additional nuances related to severity.

It's important for us to understand and maybe elevate the idea that a mild injury doesn't necessarily equal a mild outcome.

“It's important for us to understand and maybe elevate the idea that a mild injury doesn't necessarily equal a mild outcome,” Klein-Bacon said. “When we're doing training, we talk about what a mild, moderate, and severe injury looks like in terms of loss of consciousness. And because a mild injury is less severe, we also know there's a higher percentage of individuals who heal and get back to 100% baseline. But we also know from the literature that there are 15% to 20% who have moderate to severe outcomes as a result of that mild injury. They need resources and assistance, especially in rural areas where distance to specialized care is a barrier.”

mTBI: Differences Between Kids and Grownups

In its 2015 report to Congress, CDC authors wrote that “TBI is being recognized more as a disease process, rather than a discrete event, because of the potential it presents for non-reversible and chronic health effects.” Experts said that this holds true for all age groups and brain injury severity.

The CDC experts also focused on differences between adult and pediatric mild traumatic brain injury. In their 2018 report to Congress that focused on mTBI in children, the experts highlighted that any injury — even a concussion — can have a negative impact on a developing brain. The authors further emphasized that brain injury triggers changes in how children and adolescents think and in their ability to learn, socialize, and control impulses. Other issues, such as disrupted sleep patterns, depression, and anxiety, can also be triggered by an injury. The report also emphasized that “these post-TBI health problems emerge over time and are associated with significant financial and social challenges for adults having sustained a TBI as a child.”

Rural TBI Data: A Researcher's Perspective

Most recent academic reports reviewing rural TBI focus on severity of injuries in the pediatric population, including a 2020 review paper that revealed a “higher risk of dangerous injury mechanisms, trauma severity, and TBI severity compared to urban.” Yet there is a dearth of clear data around the rural causes of injury. Though experts and researchers can provide anecdotal lists of causes that include farm injuries, motor vehicle accidents, and falls, no study has focused on delineating the specific causes of rural mTBI. Therefore, current prevention efforts are based almost exclusively on urban data.

However, reviewing healthcare costs is another way to understand the impact of concussions in rural areas. In a recent paper, Washington State University researcher Dr. Janessa Graves and her co-authors used commercial insurance claims data to examine mTBI costs. In addition to noting that children with mTBI in rural areas more frequently had “polytrauma” — injuries in areas other than the head and neck — one of the paper's main findings was that healthcare costs following mTBI were significantly higher for rural children despite having lower overall healthcare utilization.

Graves said another finding from the paper raised concern: “The lower rate of psychiatry/psychology service utilization among rural children following mTBI warrants further examination, particularly given that brain injury is associated with elevated impulsivity and that youth in rural areas complete suicide at a higher rate than urban children.”

Graves explained further.

“I think that decreased mental health access is sometimes in response to stigma, also mentioned in the paper,” she said. “In my experience, it's something that parents keep mentioning over and over. Even if mental health services are present in a community, taking advantage of services is avoided because there's no anonymity in rural communities.”

Graves pointed to other research confirming the established association between TBI and suicide. Given the higher youth suicide rates in rural areas, Graves said she believes that their paper's finding of a lower rate of psychiatry/psychology service utilization for mTBI highlighted in the paper needs further examination.

“Primary data collection that includes talking directly to families regarding their needs would be very helpful, particularly for rural research on this topic,” Graves said, sharing data from another of her recent publications on hardships facing families following a concussion. Because she lives in a rural community where youth suicide is of great concern, she said that fully understanding the needs of parents and youth can better guide future injury research in rural areas.

The Practicing Psychologist's Perspective: Managing Rural mTBI

Experts recognize that rural Americans are always dealing with healthcare access issues, either due to seemingly unlimited miles to reach a specialty provider or the limited numbers of local providers, be they primary care clinicians or physical or occupational therapists. As Wyoming's Waddell noted, even urban providers will sometimes have limited timely appointment availability.

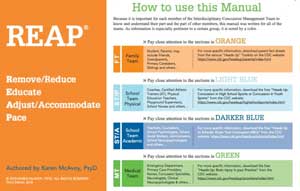

In 2009, Dr. Karen McAvoy, a pediatric psychologist, brain injury expert, and researcher who also serves on federal agency workgroups, created a tool to navigate brain injury recovery. Called REAP — for Remove/Reduce, Educate, Adjust/Accommodate, Pace — McAvoy said she originally conceptualized the tool for use in communities with scarce resources, especially rural areas. The tool, first used in Colorado, can be modified and has been adapted for use in 12 states by brain injury advocacy-service groups, schools, healthcare organizations, and others.

More about REAP

REAP provides color-coded information and guidance to 4 essential teams involved with managing a student with mTBI: family, school physical, school academic, and the medical. It provides links to additional free CDC HEADS UP resources.

Currently in private practice in Colorado seeing clients several days a week, McAvoy also travels the country providing training to hundreds of schools and interested organizations, many in rural areas or in largely rural states. She said when she wrote REAP, there was not well-defined concussion care.

“REAP was originally intended to support a student coming back to school after a sports-related concussion within a couple of days or a week of the injury with everybody pulling together in a small community to support this kid for up to a month's time,” she said.

McAvoy said she understands that in rural areas the coach might also be the science teacher and there may not even be a school nurse. REAP helps meet those challenges by describing team duties that can also be performed by other educators, school counselors, or social workers.

“I was in an urban area when we first put it to use because there was no such thing as a concussion clinic,” she said. “But, rural, urban, no matter where you are, everyone needs to have information about concussion recovery and understand that it requires a collaborative approach. With REAP, every team understands their roles and the other teams' roles.”

Like Iowa's Klein-Bacon, McAvoy said she has several important messages for rural healthcare organizations and communities. First, recognize that 40% of concussions are not related to sports, especially in rural areas. Second, that students with non-sports-related mTBI might not even be seen by a clinician. Last, even though the large majority of people with mTBI will have a very favorable outcome, there are still those outside of that statistical range that either don't get better or will have symptoms that significantly impact their life.

Symptom Wheel: Aligning Symptoms With Potential Interventions

McAvoy has also created a “symptom wheel.” Based on the premise that academic interventions are not part of a “medical clearance,” the symptom wheel helps match a student's symptoms to a suggested academic intervention. It takes into account concentration, memory, sleep, energy, emotions such as irritability and anxiousness, and physical symptoms like dizziness and balance problems.

“You can't predict who won't

recover,” she said. “It's best to

start the recovery period being cautious and using a

standardized approach, which REAP provides. We want to be

optimistic, but we also need to be prepared. Giving

people the right kind of information in the beginning

gives them hope that they're going to be in that 80% to

90%, but also gives them guidance as to when things

aren't progressing.”

Though REAP has met with great success across the country, McAvoy said its critics point to either too much information or too little information. Overall, she said it has proved a useful tool that continually gains new users. For example, two more states are in the process of adapting REAP. In addition to being included in published academic studies, McAvoy said there are also direct indicators of parental support.

“On occasion, I'll hear from parents,” McAvoy said. “They'll call me to share their story about how their child was diagnosed with a concussion and the emergency room gave them my REAP book. They make that call to thank me. It's great to know it's helping people.”

Additional Resources

- Administration for Community Living: Traumatic Brain Injury

- BrainLine

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Traumatic Brain Injury & Concussion

- Mayo Clinic: Understanding Brain Injury: A Guide for Employers

- National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke: Traumatic Brain Injury Information Page