Nov 16, 2022

Increasing Knowledge of Palliative Care in South Dakota

by Allee Mead

In November 2020,

South Dakota resident Charlene Berke's husband was

admitted to the hospital with COVID. When he was moved

from the emergency room to the intensive care unit, Berke

was sent home and was only able to see him on a video

phone call twice. During her time at home, Berke had

multiple doctors calling with updates on her husband's

health and with healthcare decisions she had to make.

In November 2020,

South Dakota resident Charlene Berke's husband was

admitted to the hospital with COVID. When he was moved

from the emergency room to the intensive care unit, Berke

was sent home and was only able to see him on a video

phone call twice. During her time at home, Berke had

multiple doctors calling with updates on her husband's

health and with healthcare decisions she had to make.

“With 30+ years in healthcare, I thought I knew some things,” Berke said. “But when you have different specialists calling you — pulmonologist, nephrologist, and hospitalists — all telling you about their specific piece, while trying to absorb this information when your emotions are extremely high is a lot. Let alone trying to relay it to other family members, who want to know what's going on.”

And it just gave me such a huge relief and comfort because [the palliative care physician] was taking that information in and synthesizing it for me and bringing it to a level that I could understand emotionally and at that time.

But then she got a call from a palliative care physician, who told her, “Okay, let's look at this from a wider perspective,” Berke said. “And it just gave me such a huge relief and comfort because she was taking that information in and synthesizing it for me and bringing it to a level that I could understand emotionally and at that time.”

The palliative care physician also helped Berke communicate medical information to family members and coordinate times to talk about healthcare decisions as well as helped Berke connect with her pastor.

In addition, since 2009, Berke and her husband had had conversations about advance care planning, so she knew what type of care her husband did and did not want. In 2020, when doctors asked Berke about putting her husband on a ventilator, she decided against it, “because I knew I would be the one in that nursing home seeing the anger in his eyes saying, 'What in the heck did you do to me? I can't be out on my boat. This is not what I want or what we talked about.'”

Knowing what her husband didn't want helped bring Berke comfort in her husband's final days. Those past conversations were important, she said, because “you don't know, is it going to be a car accident? Is it going to be something like a national pandemic? You don't know. But having those background pieces really helped with giving that peace of mind as you went forward in making those decisions and having a provider walking alongside you.”

Palliative care is often confused with hospice, which includes elements of palliative care but is for people with a terminal illness and a life expectancy of six months or less. In contrast, palliative care is designed to treat the symptoms of a serious illness at any stage of diagnosis.

While palliative care is associated with better outcomes like higher patient satisfaction and improved symptom management, people in rural areas often have limited access to these services, and many people don't understand what palliative care is.

Creating the South Dakota Palliative Care Network

While South Dakota has an “A” rating in the 2019 State-by-State Report Card on Access to Palliative Care in Our Nation's Hospitals, the specialty palliative care services that its three major health systems provide are only available in four communities. Telehealth can be an option for rural facilities associated with these health systems, but many rural and frontier communities — both in South Dakota and nationwide — do not have access to specialty palliative care services.

The South Dakota Palliative Care Network (SDPCN) began in 2018 as a way to increase access to palliative care services by increasing knowledge of palliative care among healthcare professionals, nursing students, and community members.

The work stemmed from a 2018-2019 Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP) Rural Health Network Development Planning Grant that Avera Sacred Heart Hospital received, partnering with Monument Health Rapid City Hospital and the American Cancer Society. Avera Sacred Heart Hospital, in rural Yankton, was developing its own specialty palliative care program at the time.

By the end of the grant cycle, the different components of the grant work became part of the SDPCN Strategic Plan so that the SDPCN could transition into implementing different activities. SDPCN, along with nursing programs from three academic institutions, then received a 2020-2023 FORHP Rural Health Network Development Program grant. The primary goal of this grant is the education and training about palliative care.

Focus Groups Discussing Training, Stigma, and a Statewide Model

“We did six focus groups across the state,” Berke, co-project director of SDPCN, said, “and one of the things that really came to the top was education around palliative care.” For example, even healthcare professionals were conflating palliative care with hospice. Focus groups also discussed the disparities that rural communities face in accessing palliative care as well as the need for a statewide palliative care model.

The 2021 article Perceptions of Palliative Care: Voices From Rural South Dakota discusses the six focus groups that the SDPCN held over the course of two months in two urban and three rural communities. Participants included interprofessional healthcare team members (including physicians, nurses, social workers, and spiritual personnel like chaplains) and patients and their families and caregivers.

Focus groups discussed the need for more healthcare professionals — including primary care providers — trained to provide palliative care, especially in rural areas, and recommended training professionals where they work. Participants discussed the lack of resources available in rural communities; one person told the focus group, “In a tiny little town, you're lucky to find a realtor, let alone resources to help someone like that to be assisted.”

Participants also discussed the stigma behind palliative care: If a patient and their family didn't understand what palliative care entailed, they might think that a provider was giving up on the patient. If a provider didn't understand palliative care, they might not refer patients to available specialists or services. The article's authors saw a correlation between this misconception and areas with the least access to services.

Participants said a statewide palliative care model should include elements like telehealth, education, flexibility for rural areas, a clear payment and reimbursement structure, and emotional support for patients and providers. Participants also said they wanted to see palliative care offered in settings like emergency departments, nursing homes, outpatient settings, and patients' homes and believed that offering palliative care sooner might allow patients to receive care in their own communities and not be automatically transferred somewhere else.

Reaching Healthcare Professionals and Community Members

Increasing care in the community is an important part of the SDPCN's work. “Our whole goal with educating nursing students, healthcare professionals, and the community is to get it out into all areas,” Sarah Mollman, PhD, co-project director of SDPCN, said, “not just for the persons living in our urban areas.”

Our whole goal with educating nursing students, healthcare professionals, and the community is really to get [palliative care] out into all areas, not just for the persons living in our urban areas.

The SDPCN currently has about 300 individuals from 30 organizations. Members receive updates in a quarterly e-newsletter and can connect and collaborate with one another. In addition, the SDPCN has educated over 1,500 students, 122 healthcare professionals (including physicians, nurses, advanced practice providers, social workers, and others), and 182 community members.

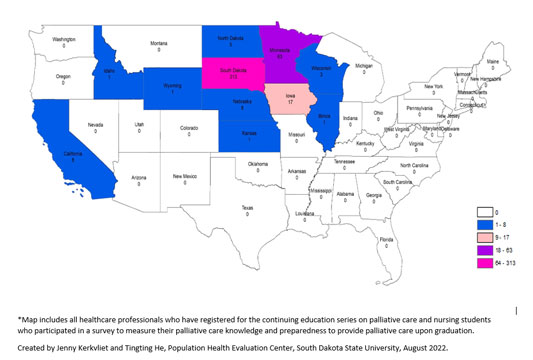

SDPCN leaders have traveled to 15 communities in the state to provide education to the public, and their online education component for healthcare professionals (11 continuing education sessions) has expanded beyond South Dakota, to 11 U.S. states and even Vietnam.

Mollman said that the goal in educating rural primary care providers is for these providers to be able to provide palliative care as part of their primary care and, if referrals are needed, know where the specialty palliative care providers are located.

“In those communities, we've been able to really provide that education around 'What is palliative care?'” Berke said. “It's really hard for people to get their head wrapped around that because in those communities they're struggling to even have home health or hospice.” When communities lack these types of services, the conversation can shift to things like advance care planning, living wills, powers of attorney, and available community resources.

Community presentations tend to be 20-30 minutes long, and attendees will stay an hour or longer after the presentation to ask questions. Berke said a one-on-one conversation is not “the most efficient way to educate, but it is pretty impactful.”

I learned over several sessions to talk less and open up for questions more and just let the community lead the conversation.

Mari Perrenoud, SDPCN director, speaks at these community presentations. The hour-long conversations afterward are also a time for community members to share their own experiences with palliative care. “Everybody has a story,” Perrenoud said, “and it may be their parent, it may be their spouse, it may be a sibling. Heaven forbid, it's a child.” Because these conversations take place in rural communities, many of the other attendees know the person involved. “I learned over several sessions to talk less and open up for questions more and just let the community lead the conversation,” Perrenoud added.

Berke shared that healthcare professionals benefit from these educational sessions as well: “They used to really hesitate on sending a patient to a specialist, but now they have a better understanding of what that specialty is in palliative care and when to refer.”

“We're showing that we can increase their knowledge and preparedness to provide primary palliative care,” Mollman said.

One key component of SDPCN's work is a common vocabulary and consistent messaging. In conjunction with other grant teams focused on palliative care education, Mollman said, “We've created the statewide definition of palliative care. We have that consistent messaging when we're doing our education. We all based our education off the national clinical practice guidelines. When we all work together, it creates a consistent message and furthers the work so that we're not duplicating anything.”

South Dakota Statewide Definition of Palliative Care

The statewide definition of palliative care is a modified version of the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) definition and is as follows: “Palliative care is medical care for people living with a serious illness. This type of care is focused on providing relief from the symptoms and stress of illness with the goal to improve quality of life for both the patient and family. Effective palliative care is delivered by a trained team of doctors, advanced practice providers, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and other health professionals who collaborate to provide an extra layer of support. Based on the needs of the patient, not on prognosis, palliative care is appropriate at any age and any stage of serious illness and may be provided alongside curative treatments in primary and specialty settings.”

Challenges and (Grant) Opportunities

The Rural Health Network funding has allowed the SDPCN to bring its different palliative care projects together, Berke said: “We have three funded projects from outside funders in regard to palliative care education. And the HRSA funds have helped us pull all of those groups together.” In addition, the grant funding allows for two full-time positions to implement its work.

The SDPCN is holding a palliative care symposium in rural Yankton this November — a hybrid event so healthcare professionals, students, clergy, and others can attend online or in person. “We're really, really excited about that,” Mollman said. “This is just above and beyond what we thought we could do.” Topics for the symposium include maternal-fetal palliative care, medical cannabis, symptom management, and family meetings.

One challenge the SDPCN faced in its grant-funded work was the COVID-19 pandemic, as leaders had to shift planned in-person events to a virtual format and learn how to build trust and relationships through webcams. “The good part about [the pandemic] is it really heightened awareness of the need for palliative care education,” Berke said, especially the need for conversations about advance care planning and goals of care.

Mollman said that different clinicians, organizations, and others have “competing priorities” and limited time to attend educational sessions, so it's important to explain why palliative care education is important to these different groups.

Mollman credited SDPCN's success with administrative buy-in as well as the FORHP funding. For organizations looking to create a similar network, she suggested investigating whether your state has legislation or funding to support palliative care and education. Berke had additional advice: Stay flexible and make sure to listen to partners in order to understand their needs and priorities.

Looking to the future, SDPCN leaders want to incorporate conversations about advance care planning into the primary care setting, explaining that patients and family members want to have these conversations but don't know how to bring up the topic. SDPCN leaders want to take an interprofessional approach, since “you never know where those conversations are going to resonate most with patients or families,” Berke said, “whether it's at the front desk when they're checking somebody in or when that patient is visiting with the nurse or the provider.”