Nov 03, 2021

It Takes a Village: Rural Recruitment and Retention

by Allee Mead

Benjamin Anderson, former CEO of Kearny County

Hospital in Lakin, Kansas, remembers when his hospital

and five or six others in the area decided to work

together to recruit family medicine physicians finishing

up their residencies. They collectively approached

residency programs “and we said we want to

recruit 15 or 20 primary care doctors out

here,” Anderson said. “We are not as

concerned with who goes where. We're not going to fight

over this doctor or that doctor.”

Benjamin Anderson, former CEO of Kearny County

Hospital in Lakin, Kansas, remembers when his hospital

and five or six others in the area decided to work

together to recruit family medicine physicians finishing

up their residencies. They collectively approached

residency programs “and we said we want to

recruit 15 or 20 primary care doctors out

here,” Anderson said. “We are not as

concerned with who goes where. We're not going to fight

over this doctor or that doctor.”

Working collaboratively also allowed these hospitals to pool resources and host what they called “focus weekends” or “fly-in weekends.” The hospitals shared the costs of hotel rooms for the potential recruits and conference rooms for meetings, and hospital CEOs personally provided ground transportation. Wealthy farmers and other business owners lent private planes to fly recruits to the area and a state farm bureau funded a steak dinner. A local zoo held a private event where the recruits and their families could feed some of the animals. Immigrant and refugee community members hosted meals to showcase the cultural diversity in the area.

The hospitals hosted three focus weekends, resulting in a total of 20 physicians signing contracts with a participating hospital. Anderson said the recruitment effort was so successful his hospital stood to lose its Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) status and needed a governor's exemption in order to keep its Rural Health Clinic status.

When we pooled all those resources together, we figured out we have the resources of a more urban area. There was a compounding effect, a realization that we're better together.

“When we pooled all those resources together, we figured out we have the resources of a more urban area,” Anderson said. “There was a compounding effect, a realization that we're better together.”

“We're better together” is an excellent approach for recruitment efforts. Whether or not rural healthcare facilities are able to partner with nearby hospitals and clinics, they can partner with community organizations and local businesses and individuals to improve the job interview experience and help new employees quickly become and remain engaged in the community.

First Impressions

It can be difficult to recruit healthcare professionals to rural areas for a variety of reasons. Job candidates might worry about a heavy workload or isolation, while rural facilities may struggle to compete with urban facilities in terms of salary or benefits.

Mark Barclay is director of member services at 3RNET, a national membership association. Barclay provides technical assistance, training, and other resources to 3RNET's national network of coordinators. “I work a lot with the employers that are using 3RNET to post their jobs and then the healthcare professionals that are trying to connect to those jobs,” he said. His organization helps job candidates understand what it's like to work in rural and underserved areas and find employment opportunities while also helping healthcare facilities improve their recruitment and retention efforts.

“A lot of rural employers struggle with the capacity to have dedicated staffing and resources to do recruitment well, so we try to help build their capacity,” Barclay said. He explained that many rural facilities do not have staff members solely dedicated to recruitment or marketing; these employees often fulfill multiple roles and don't have the time or resources to improve hiring efforts.

This lack of a dedicated recruiting/marketing person can affect job candidates' first impressions of a rural healthcare facility. “A lot of the first impressions of rural and underserved communities for the last 10 or so years have been happening virtually,” Barclay said, adding that a job candidate may have a negative impression of a facility whose website “looks like it was built in 2001.”

Addressing the Challenge of Rural Housing

Housing is a huge concern in rural areas, as a community may face a shortage of available or affordable housing for new providers. Mark Barclay from 3RNET shared that some healthcare organizations are buying rental properties in their communities so that housing is available for locum tenens, medical students completing rotations, or new employees who need temporary housing while they look for a home that best fits their needs. “For an organization to have temporary housing that they can provide as an incentive really takes a lot of the pressure off the healthcare provider coming in,” Barclay said. Healthcare organizations can also reach out to the local bank and landowners to come up with housing solutions.

First impressions are also crucial when

a healthcare professional visits a rural community during

the job interview, as Pat Bertagnolli can attest to. He

is the Community Enhancement Director for the Rough Rider

Center (a community center) in Watford City, North

Dakota, but he works closely with McKenzie County Healthcare

Systems and its 24-bed Critical Access Hospital to

welcome job candidates and new hires into the community.

First impressions are also crucial when

a healthcare professional visits a rural community during

the job interview, as Pat Bertagnolli can attest to. He

is the Community Enhancement Director for the Rough Rider

Center (a community center) in Watford City, North

Dakota, but he works closely with McKenzie County Healthcare

Systems and its 24-bed Critical Access Hospital to

welcome job candidates and new hires into the community.

Bertagnolli, who grew up in rural Montana, worked for a delivery service company for 22 years until a friend of his said he was moving back to Watford City and wanted to hire Bertagnolli in a human resources position. Bertagnolli went to Watford City for a job interview and met some locals. When he was leaving a restaurant, the owner said, “Hey, Pat, it was really nice meeting you. And I certainly hope you'll consider joining our community. We'd love to have you.” Bertagnolli said that gesture alone sold him on moving to North Dakota.

He remembers one success story at the hospital that demonstrates the power of first impressions. A hospitalist from Florida applying for a job at McKenzie County Healthcare Systems visited North Dakota when it was -25 degrees outside (-40 degrees with wind chill) and still took the job because she was so impressed by the hospitality and community spirit. “It can be done,” Sam Perry, former Senior Director of Operations & Ancillary Services at the hospital, said, “but it can only be done by having confidence in your organization and confidence in those around you.”

Focusing on Families

Barclay said that a healthcare organization needs recruiters within the facility but also in the larger community, including the school board, the chamber of commerce, and the banking industry. “What makes the community's role different in rural and underserved areas is that you're really trying to sell somebody on the entire community as opposed to just a job,” he said. “If you take a job in Chicago, you can assume that you're going to have access to essentially all of the services and resources that you would need. If you take a job in a community of 750 people, it's not as clear-cut that you'll have options for schooling and for grocery stores.”

What makes the community's role different in rural and underserved areas is that you're really trying to sell somebody on the entire community as opposed to just a job.

Just as a healthcare professional needs to consider the larger community before taking a new job, a rural healthcare facility needs to consider the needs of a job candidate's family, not just the individual. Chrysanne Grund has worked for Greeley County Health Services (GCHS), an integrated health system in Tribune, Kansas, in different roles for 28 years. Her current role as project director includes assisting with recruitment efforts.

“We believe very much that we're recruiting not only the individual, but their family when they come,” Grund said. During GCHS's recruitment efforts, she and her team pair job candidates with individuals who have similar needs and interests. For example, if a job candidate has young children, her team will pair the candidate with a healthcare employee or community member who has insight into the community's child care and schools. Grund said that her own children are in their twenties: “I don't know what a person with a six- and a four-year-old is looking for in the rural community right now.”

During a visit for a job interview, local businesses offer food or provide fun activities for the family members. These same businesses also agree to help integrate the job candidate and their family into the community if the candidate accepts the job. Recently, a physician came to GCHS for a job interview. He, his wife, and their teenage boys had lunch at the bowling alley and later played disc golf. Then the family had dinner at a GCHS employee's home with all the professional staff. The wife, a teacher, also had a chance to visit the area schools and discussed job opportunities.

“It was a wonderful experience,” Grund said. “He and his family have been out to visit several times and are in the final stages of buying a house. He will come to us summer of 2022. They were able to stay at a house next door to the hospital, loaned to us by a board member.”

National Health Service Corps (NHSC) Sites

Greeley County Health Services is an NHSC-approved site. NHSC-approved status helps healthcare clinics recruit and retain clinicians by offering loan repayment as an incentive. Clinicians at NHSC-approved sites like Greeley are eligible for NHSC loan repayment programs, which offer loan repayment assistance in exchange for 2 or 3 years of service. NHSC sites can also increase their job openings' visibility by sharing their jobs on HRSA's Health Workforce Connector and participating in HRSA's virtual job fairs.

McKenzie County Healthcare Systems also partners with the

local schools. Bertagnolli has what he calls an

ambassador program at the local high school made up of

athletes, student council members, and Students Against Destructive

Decisions members. These students meet with job

candidates, give school tours, and explain how they help

welcome new students if the candidates have school-aged

children.

Helping New Employees Stay Engaged

In addition to recruiting job candidates and their families, healthcare facilities need to consider how to get — and keep — the new staff members engaged within the larger community. Perry argues that it's important for healthcare providers to become involved in the community for their own sake: “By having regular activities both in and out of work, recruits (and their families) are much more likely to be retained and become part of the community in the long run.”

Your nurse one day can be leading the choir at church and the lab technician who drew your blood yesterday may be coaching your child's sports team tomorrow night. This engagement is what really retains employees, not just salary, and this engagement is what we have tried to focus on by introducing both the employee and their families into the community.

Perry said that people in rural communities wear multiple hats. “Your nurse one day can be leading the choir at church and the lab technician who drew your blood yesterday may be coaching your child's sports team tomorrow night,” he said. “This engagement is what really retains employees, not just salary, and this engagement is what we have tried to focus on by introducing both the employee and their families into the community.”

Grund from GCHS shared that her facility is working on engaging with new employees after they've been hired: “We have tried to do a little better job of remaining connected with those families once they enter the community.” This task isn't always easy, however. Grund admitted that it can be difficult to know how to best reach out to a new employee who is single or without other family connections, although employees with no family in town especially need this type of support.

Anderson, the former hospital CEO, said that while the hospitals in Kansas were successful in recruiting family medicine physicians to the area, the physicians told him that they didn't feel welcome outside of work. He said, “This is the feedback that we're getting from the physicians we recruited there: 'Everyone's friendly but I don't have any friends' or 'This is a wonderful place to practice medicine if I just had family here' or 'I haven't had a date with my spouse in a month and a half or two months or six months, but there's no one willing to watch our children.'”

This feeling of isolation can put a strain on healthcare professionals' mental health as well as their relationships. Anderson himself babysat a couple's children so the physician and physician assistant could have a date night for the first time in months: “I remember [the husband] saying that was worth more to him than a $50,000 retention bonus.”

Rural folks can be slow to warm up to new community members, Anderson said, but there are ways to help new providers feel welcome sooner, such as having four or five families in the community act as ambassadors. In his experience, immigrant families were the most influential in keeping providers in the community because they can empathize with moving to a new place and because “they actively need the same support.”

…there's got to be a deeper commitment to hospitality…

Anderson said that “there's got to be a deeper commitment to hospitality” in the healthcare facility and larger community. He added that the effort needs to be done “similar to how we would launch a pain management or orthopedic service line” — for example, by determining a budget and creating a list of measurable goals and accountable stakeholders.

Six Questions to Guide Recruitment Efforts

Benjamin Anderson, now Vice President of Rural Health and Hospitals for the Colorado Hospital Association, said that an effective recruitment tool he's used over the years came from Elizabeth Teisberg, PhD, at the Value Institute for Health and Care. It's a six-question tool:

- What outcome are we trying to improve?

- Who are the stakeholders? Who would care that this outcome improves?

- What information or resources can those stakeholders share to improve that outcome?

- Why isn't it already happening? What barriers exist?

- How do we measure the success of this?

- When do we expect to see progress?

Anderson said leaders need to approach these questions with humility. “The answers don't come from the person posing the question,” he said. “The answers come from the people on the receiving ends of them.”

Inviting People In

Bertagnolli from North Dakota suggests that one way to think deliberately about recruitment is to bring in people from outside the community who can identify strengths that people living there may take for granted. In addition, he often asks employees and community members to articulate why they themselves live where they do and what makes them stay.

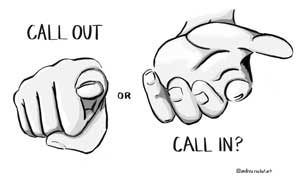

Anderson's advice for encouraging hospital employees, community members, board members, and others to join recruitment efforts is to call them into the work instead of calling them out. He remembers a time when a board member congratulated him on his recruiting efforts then asked how he'd be able to sustain it long-term. (Anderson and his family had become exhausted doing this work largely by themselves due to others' lack of interest.)

Frustrated, Anderson told the board, “If you want to ensure the sustainability of this, have these people over to your home for dinner.” One board member became defensive at his tone. Anderson realized later that a better approach to getting stakeholders involved is saying, “This work takes everybody. We need you to be part of the solution. Will you join us in this really important work, as it can make a big difference for our community?”

Recruitment and Retention Topic Guide

You can learn more about the challenges of and available resources for recruiting and retaining healthcare staff in the RHIhub Recruitment and Retention for Rural Health Facilities topic guide.