Oct 28, 2020

PharmD Concentration Helps Pharmacy Students Prepare for a Career in Rural America

by Allee Mead

Taylor Hauser is a fourth-year pharmacy student at the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy and a member of the inaugural Rural Pharmacy Practice cohort. She grew up in Argonne, Wisconsin, which does not have a hospital. When she was a child, her family's pediatrician was in a different county, so going to the doctor involved Hauser's parents taking off a day of work.

However, the neighboring community, Crandon, did have a pharmacist, and her family would go to him with medical questions. For example, if someone had a rash, the pharmacist could take a look and let the family know if they could treat it at home or needed to see a doctor. This pharmacist inspired Hauser to pursue pharmacy herself.

“I've always wanted to come back to Argonne and increase access to healthcare resources because I know that they can be sparse in some of the rural areas of Wisconsin,” Hauser said. When she heard about a new concentration for PharmD students interested in becoming rural pharmacists, Hauser said she immediately knew she wanted to apply.

Jenevieve Van Order is also a fourth-year pharmacy student at UW–Madison. Growing up in rural Arbor Vitae, Wisconsin, she knew she was interested in healthcare but didn't know what exactly she wanted to do, until she took a career aptitude test and the top result was “pharmacist.”

Like Hauser, Van Order intends to return to her rural community after graduation in 2021 and knew that the Rural Pharmacy Practice program was for her. “Growing up in a rural area,” she said, “I saw the gaps in healthcare in rural areas. I wanted to do something that would give me more tools and more resources to help fill those gaps when I get home.”

The Rural Pharmacy Practice program, which first began in the fall 2019 semester, is a two-year concentration that occurs during the last two years of PharmD students' education. Rural practitioners share their experiences with students, and students learn about the importance of community partnerships in delivering coordinated, high-quality care. Then students go into rural communities and work with stakeholders to implement a project to improve community health. Students also receive mentorship from a rural practitioner.

“Our students are not taught to come in with answers,” Ed Portillo, PharmD, said. “They're taught to come into a rural community with questions and to be co-creators for change.”

Portillo is an assistant professor at the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy, in the Pharmacy Practice Division. He practiced at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in urban Madison, which serves a high percentage of rural patients who had to travel to receive care. This experience helped him understand the barriers to care that rural patients face as well as the unique opportunities that smaller communities provide. Portillo led the development of the Rural Pharmacy Practice program.

Portillo is involved with developing the rural health curriculum at UW–Madison. One of his goals, he said, is to “give our students a clear pathway from their curriculum here at the School of Pharmacy to rural practice.” He added that it's important to get students not only interested in rural practice but also prepare them “to be positive collaborators and community members in rural practice settings.”

Creating a Concentration from Scratch

Portillo started developing this program by talking to rural practitioners and patients in the state and asking what skills pharmacy school graduates needed in order to best serve rural communities.

Working with Portillo is Kevin Look, PharmD, PhD, an assistant professor at the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy, in the Social and Administrative Sciences Division. His research focus is on health policy and the impact of state policy changes on patients' access to care and the cost and quality of that care, and he has studied rural pharmacies.

Look was part of the team of faculty involved with the development of the Rural Pharmacy Practice concentration. He said the team received top-down support, including from the dean of the School of Pharmacy, and organized focus groups with students.

The process of creating this program, he added, took years “to understand and educate ourselves on what has to happen to really produce the change agents for driving rural healthcare.”

Portillo found it to be both a challenge and an asset to create a program like this from scratch. Since there weren't other programs they could model, they had to rely on their partnerships and on focus groups of practitioners, many of whom are still involved with the program. “If we had just mimicked what another school did, we would have missed out on all these opportunities to really learn from the people doing this great work,” he said.

Presentations and Community Projects

In discussing the program's curriculum, Look said that the first half of each two-hour class focuses on content, such as the definition and purpose of community needs assessments. In the second half of the class, rural practitioners, often UW–Madison alumni, come into the classroom and talk about their experiences practicing in rural communities and answer students' questions. This fall, rural practitioners will talk with students through teleconferencing, which will save them travel time and costs.

Students complete a semester-long community needs assessment and a year-long project in which students develop an initiative in a rural community. The course sequence also emphasizes project management, so the students learn how to bring their idea to fruition and can apply that knowledge to their projects.

“[Students] want to be part of the solution for further improving healthcare, but we need to give them the tools, resources, connections, and mentoring to do that.

Students, Portillo said, want to be involved: “They want to be part of the solution for further improving healthcare, but we need to give them the tools, resources, connections, and mentoring to do that.”

The Rural Pharmacy Practice program partners with five Wisconsin communities: Baraboo, Monroe, Montello, Portage, and Prairie du Sac. At the end of their community needs assessment, students share what they learned about their communities and discuss similarities and differences.

When students are assigned to a rural community, they first complete a “windshield assessment” by driving through the town. “We have them do some research on the town,” Look said, “learn a little bit more about its history and learn about characteristics of the county that it's located in.” In addition, students interview pharmacists and county health department staff as well as patients.

Students Van Order and Hauser completed their semester-long project in Monroe: a community needs assessment where they talked to pharmacy staff and patients. Hauser said this type of assessment was the most important thing she's learned from the program so far. “You don't want to go into a rural community and say that they need a mental health program or they need this, they need that,” Hauser said, “when, depending on the community's needs, they might not actually need or want those services in the area.”

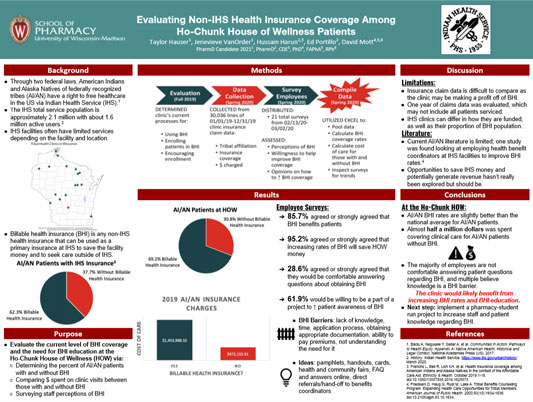

For their year-long project, Van Order and Hauser worked with Ho-Chunk House of Wellness, an Indian Health Service (IHS) clinic in Baraboo. While students typically work with the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital and the Wisconsin Office of Rural Health for their projects, Van Order and Hauser talked to Portillo about establishing a formal partnership with IHS.

After talking with their project mentor, Ho-Chunk House of Wellness director of pharmacy Hussain Harun, PharmD, the students decided to look at health insurance coverage. While American Indian and Alaska Native people from federally recognized tribes are eligible to receive IHS services, they may also qualify for private insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid — especially important if they receive care from a non-IHS facility. Van Order said it creates “a reimbursement avenue for Ho-Chunk House of Wellness when patients visit and have a billable health insurance.”

Van Order and Hauser's project involved collecting coverage data and evaluating what the clinic's process was if a patient came in without a billable health insurance. The clinic created a spreadsheet of all medical claims from 2019. Van Order and Hauser found that 30.8% of patients did not have a billable health insurance, which they said is lower than the national average for American Indian and Alaska Native populations but higher than the national average for any other racial demographic.

Van Order and Hauser also determined how much money the clinic spent on care that could have been billed to insurance. Congress allocates money to IHS sites; any money not spent on covering patients' care can be used for other resources like hiring new employees or starting a community resource.

Van Order and Hauser also surveyed Ho-Chunk House of Wellness staff to learn their thoughts about starting an initiative to increase billable health insurance. This information helped Van Order and Hauser gauge staff willingness as well as any staff education needed to implement this initiative.

At the end of the year, students create a poster they can share at national presentations, write a paper they can publish in a journal, and present their findings to the class. “It's not enough to just be innovative in your own pocket,” Portillo said. “You have to spread that innovation and share your work with others.”

Benefits to Students and Practitioners

There are 16 students in each cohort of the Rural Pharmacy Practice program, working with five faculty members. Portillo said that the first cohort of students has reported an increased comfort in working with other healthcare team members.

It was really nice to hear from people who are out working in a rural community, because I'm from a rural community. And it was just nice to see them being represented in our school coursework.

Hauser appreciated seeing her school prioritize rural health and bring in speakers from rural communities. “It was really nice to hear from people who are out working in a rural community, because I'm from a rural community,” she said. “And it was just nice to see them being represented in our school coursework.”

Van Order said the Rural Pharmacy Practice program “does a really good job of introducing you to a lot of different innovative models and how other people are using them.” She also appreciated learning about project management, especially managing time and adapting quickly to changing situations.

The program really helps equip you with the tools and resources that you would need to be an innovative practitioner in a rural community once you get out of school.

Van Order added, “The program really helps equip you with the tools and resources that you would need to be an innovative practitioner in a rural community once you get out of school.” She said the skills she's received through this program will help her and other students improve the health of their communities.

The preceptors benefit from this program as well. Maria Wopat, PharmD, BCACP, CTTS, is a clinical pharmacy specialist at William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison. She is the pharmacist for three different teams within the primary care clinic. She works with urban as well as rural veterans on chronic disease management.

Wopat was approached by Portillo, who asked what she felt was missing from her practice. She said that her practice hadn't been screening for osteoporosis and patients were being undertreated. Rural Pharmacy Practice students then had the opportunity to work with rural veterans in the Team Osteo project.

In Team Osteo, patients over 70 qualify for an initial DXA scan (to measure bone mineral density) to see if they have osteoporosis. Rural Pharmacy Practice students complete screening calls, ask the rural patients to come in for a DXA scan, and complete a chart review to see what risk factors the patients have.

Wopat said anywhere from three to five students help her with this project each year, saving her and her staff time and helping students gain valuable experience. “When this opportunity came along to work with a certain smaller group of students over a year's worth of time, while doing a project that I felt pretty passionate about, I definitely jumped at the opportunity,” she said.

Wopat helps students with their communication skills and preparation for their residencies. She said she especially enjoys seeing how students' “communication skills grow. Their comfort level of talking with patients grows, and they become more efficient.”

She remembers one Rural Pharmacy Practice student who was comfortable talking with faculty but became nervous and unsure when talking to patients. “Even though she had the script laid out for her,” Wopat said, “she would do a lot of digging through the charts to make sure she knew everything about the patient, which, at the end of the day, is not realistic.” Wopat coached her and gave her feedback, and the student's confidence level grew.

…think about projects that you feel like you haven't had a lot of time to devote to and think creatively about how you can get students involved in that.

Her advice to pharmacists interested in becoming mentors or preceptors for a program like this is to “think about projects that you feel like you haven't had a lot of time to devote to and think creatively about how you can get students involved in that.” While practitioners might worry about the extra workload that might come with adding a student, Wopat said that students have years of education and an existing skillset to bring to the table.

Pharmacists and the Rural Perspective

Look said that a large number of students, like Hauser and Van Order, in the pharmacy program are from rural areas and want to return to their hometowns or work in another rural community after graduation. He's even seeing students from urban areas interested in learning more about rural pharmacy work.

Whether or not a pharmacy student ultimately chooses to practice in a rural community, Hauser said that “it's important for providers at urban facilities to realize some of the challenges that might exist for their rural patients, such as transportation to these sites,” instead of writing off patients who miss appointments as “noncompliant.”

Van Order said that, since many patients see a pharmacist more often than they see a physician, “pharmacists are the most accessible members of the healthcare team. So you really have the opportunity to step in and make a difference in patients' lives.”