Apr 19, 2017

Rural Health Literacy: Understanding Skills and Demands is Key to Improvement

Related Articles

This is the first of the 2017 two-part series dedicated

to the rural aspects of health literacy. Read part two –

Rural

Health Literacy: Who's Delivering Health

Information?

In 2022, another two-part series addresses this topic:

A New

Era of Health Literacy? Expanded Definitions, Digital

Influences, and Rural Inequities and Educating

Future Healthcare Providers: Health Literacy

Opportunities for Webside Manners

Health literacy horror stories. Every rural physician has one. The diabetic patient who was told to decrease sugar intake by stopping their six daily sodas? Replaced them with six “healthy” juice drinks, high in fructose. Or, that patient who smiled and nodded when instructed to take one heart pill daily with a meal? The emergency room staff treating the patient's dizziness discovers that one pill was taken daily, but with each meal.

Health literacy, “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions,” was first assessed in 2003 as a specific component of the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) survey. It is the first—and to date, the only—comprehensive national measurement of health literacy and still serves as the baseline measurement.

The dismal results of the 2003 assessment got attention. According to rural health literacy researcher and family medicine physician Dr. Paul Smith, those results still get attention. Smith, also a professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, has included those results in nearly 200 lectures over the past decade.

When I give audiences the statistics that a third to half of Americans have trouble just reading, and then I tell them that only one in ten of all Americans have any proficiency with understanding health information, they sit in stunned silence.

“When I give audiences the statistics that a third to half of Americans have trouble just reading,” Smith said, “and then I tell them that only one in ten of all Americans have any proficiency with understanding health information, they sit in stunned silence.”

Smith also notes for the 10% of adults considered proficient by health literacy standards, stressful situations can decrease their health information processing skills.

“Even for the folks who do have proficiency, all you have to do is to give them a cancer diagnosis, make them sleep deprived, experiencing severe pain, any of those things that happen all the time in a hospital or an emergency room,” he said. “Anybody, anybody with those things happening is going to have trouble processing, remembering, or making decisions related to healthcare information.”

One Survey, Many Insights

Specific rural health literacy information has been pulled from the original 2003 NAAL data. In 2009, the study, Health Literacy Skills in Rural and Urban Populations, was published in the American Journal of Health Behavior. As one of the first studies specifically looking at health literacy in rural populations, the researchers found that rural populations had lower health literacy. But these results came with an important disclaimer: “after adjusting for known confounding variables, however, we found there was no longer a significant difference in health literacy between these two [rural and urban] populations. Thus, the lower health literacy scores in rural areas can essentially be explained by differences in age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, and income.”

Eight years later, Smith still has a similar take. When it comes to the troublesome national health literacy statistics, rural and urban are not equal.

Everything is harder for rural folks. Harder to find, to use, to understand.

“Everything is harder for rural folks,” Smith said about health information. “Harder to find, to use, to understand. It's all harder for rural areas, especially with the lower educational achievement levels.”

Along with the prevalence issue, the economics of low health literacy can't be ignored. Health literacy experts and researchers point to a frequently cited 2007 financial analysis to show costs. In the report Low Health Literacy: Implications for National Health Policy, again based on the 2003 NAAL data combined with 2003 expenditure data, analysts demonstrated that low health literacy cost the nation's health care system somewhere between $106 and $238 billion dollars.

Health literacy also impacts morbidity and mortality rates. According to the 2010 National Action Plan to Improve Health literacy, “studies have linked limited health literacy to misunderstanding instructions about prescription medication, medication errors, poor comprehension of nutrition labels, and mortality.”

The fourteen-year-old NAAL data has been well-processed. It has stimulated research, rural and urban alike. But, rural health literacy researcher and expert Dr. Kristie Hadden, executive director for the University of Arkansas for Medical Science's (UAMS) Center for Health Literacy, said that though the original assessment measured only the “skills side” of health literacy, it's shed light on the importance of a second side of health literacy, the “demands side.”

“The national literacy and health literacy survey, the NAAL, hasn't updated health literacy data on population levels since its administration in the early 2000s.” Hadden said. “While current measures are focused on individuals' skills at finding, understanding, and using health information, there is actually more to health literacy. It's not just about patients' skills, it's also about system demands.”

Understanding Both Sides of Health Literacy: Skills and Demands

Health literacy leaders like Hadden said that it's important to understand both the skills and demands sides of health literacy.

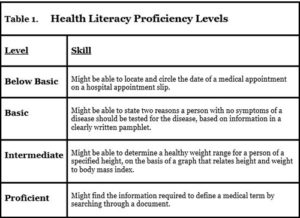

On the skills side, health literacy is measured as a proficiency, explained by a patient's skill in completing a task (Table 1). For example, being able to circle an appointment date on a hospital slip might be considered a “below basic” skill. In contrast, a patient who is “proficient” might be able to search a document and find a medical term definition.

The other side of health literacy, the demands side, is the “knowledge, skill, and cognitive effort that are part of a health-related task,” a definition from one of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) health literacy training modules.

Examples of the demands side of health literacy are activities like filling out complex forms with legal jargon, trying to understand information with complex numbers, or instructions crammed full of words with no pictures. Medications, too, demand an understanding of different dosages, time schedules, and methods to administer. Lastly, the demands side of health literacy also includes navigating through complex health systems in order to see multiple specialists, making appointments, having a procedure, also along with understanding insurance and payment information.

Using these examples, experts and researchers like Hadden recommend that healthcare providers and health systems evaluate what they are asking—no, what they are demanding—of patients, noting it's important to stop the focus on how well an individual can master health information, and instead, shift the focus to making that health information easier to understand–and to receive.

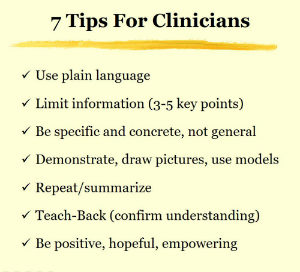

Linking Health Literacy and Health

Clinics and hospitals can do a self-evaluation of the demands they are placing on patients. Strategies include using plain language on all forms, highlighting key facts, making sure information is clear, simple, and jargon-free. Another action plan is making sure the check-in and appointment processes are patient-centered. Even taking a look at building signage to make sure lab and X-ray areas are color-coded, or marked using pictures instead of words can be helpful.

Experts point out it's not easy to measure success associated with lessening the demands side of health literacy. But, most advocate that health outcome measures will best represent the effort. For example, will that diabetic's blood sugar be improved and maintained? Will patients stop smoking and not relapse? Will our colon cancer rates go down because screening was better understood and completed? Sustained positive outcomes like these will become the new surrogate for looking at health literacy improvements, as researchers and experts suggest that improving literacy should ultimately be matched to improving health.

Dr. Marin Allen, deputy associate director for Communications and Public Liaison and director of Public Information in the Office of the Director at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), said she agrees it's time to take a closer look at the demands side of health literacy. In their National Academy of Medicine's Health Literacy Roundtable's discussion paper, Considerations for a New Definition of Health Literacy, Allen, along with her colleagues, suggest that a new definition might even provide increased focus and support for that demands-focused research and approaches.

We spent a decade on one-on-one health literacy of the individual…Now we're looking at how systems can help people understand their overall health better.

“We spent a decade on one-on-one health literacy of the individual. Then it was the communication between the provider and the individual in need of health information. Now we're looking at how systems can help people understand their overall health better.”

Healthcare organizations wanting to improve the demands side of their patient information can find help and suggestions from several organizations:

- AHRQ's Guide to Implementing the Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit

- CDC's Health Literacy information

- NIH's Health Literacy: Saves Lives. Saves Time. Saves Money.

- Health Resources and Services Administration's (HRSA) health literacy information

Demands-Focused Health Literacy Research: Understanding and Engaging the Patient Audience

Health literacy experts also point out that health information needs to be audience specific since it gets filtered by culture, individual experiences, and environment.

Dr. William Elwood, health scientist administrator at NIH's Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, said it's important that health literacy information and research aligns with what groups know so “they can apply that to whatever a new health need would be.”

“Health literacy is individual, it's regional, it's social,” Elwood said. “For example, people in agriculture already know what to do to protect themselves from herbicides, pesticides, insecticides. This is a common practice, they even have short-hand terms for it, it's second nature. They will use the skills they have learned for that to make other informed health decisions.”

For example, people in agriculture already know what to do to protect themselves from herbicides, pesticides, insecticides…They will use the skills they have learned for that to make other informed health decisions.

Elwood's perspective fits with the tested approaches for researching the demands side of health literacy. Experts and researchers said important methods include not only simplifying forms and processes, but engaging the intended patient audience for collaboration and process feedback before the research or any process change starts. UAMS's Hadden shared a recent example of how advanced engagement helped her team design a research project.

“My research team reached out to patients with diabetes in our rural primary care clinics to ask them how they would prefer to receive diabetes education before we launched our project,” Hadden said. “We asked them if they would prefer education via phone call, text, on their patient portal or in person. The feedback was a resounding 'Do NOT text me,' and 'what's a patient portal?' That feedback was very enlightening.”

Dr. Debra Moser, another rural researcher, also said getting participant feedback before starting rural research projects is a strategic step. Moser, Professor and Gill Chair of Cardiovascular Nursing, and Director, RICH Heart Program at the University of Kentucky, said since research tries to solve health problems, understanding a rural community's problem-solving culture is a must for insights around study interventions. Like Hadden, she shared a recent experience.

“When we interviewed a community to see the best way to deliver our research intervention, they decided to take us to a really rural area with a church near a lake,” Moser said. “It was dusk, and we were told to be quiet as we entered the church. They had us look up. There were literally thousands of bats hanging up there. Bat guano was all over the chairs. They couldn't hold services.”

As the group moved outside to watch the bats leave the church into the night, Moser said the community field guides ignored her team's condolences for the loss of their church. Instead, the guides shared their community's problem-solving approach that would save the church — and the bats — an approach Moser and her colleagues then used to structure the demands side of their research intervention.

Moser said an early look at their yet unpublished data showed the impact of pre-engaging the study group. Patient enrollment numbers were met before the study started, participant retention was excellent, and results favored the intervention. She said this experience is representative of other projects she's led: understanding the rural demands side means “understanding the core of what's important to people and how to make things culturally appropriate.”

I always say that when we start on the litany of things that are wrong with rural areas, they are poorer, they are sicker, they are older, have worse everything including health literacy, that the strengths of people in rural areas are often ignored.

“I always say that when we start on the litany of things that are wrong with rural areas, they are poorer, they are sicker, they are older, have worse everything including health literacy, that the strengths of people in rural areas are often ignored,” Moser said. “People in rural areas tend to be more oriented to improving their community, they are not so self-interested. It's more about improving the health of the community, the health of youngsters as well as the older folks. And they really believe in the homegrown change.”