Oct 17, 2018

The Ruralness of Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence: Prevalence, Provider Knowledge Gaps, and Healthcare Costs

Back to Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence: Some Do's and Don'ts for Health Providers

Over the past decade, several academic papers have assigned prevalence rates to rural domestic violence (DV). A 2009 study, using 2005 data from 16 states, indicated that DV and intimate partner violence (IPV) were significant public health problems in rural areas, though rural and non-rural prevalence rates were similar. Another frequently cited 2011 paper that used 2008 survey data from over 1,400 female Iowans seeking abortions showed that “rural women experience higher rates of IPV and greater frequency and severity of physical abuse.” This 2011 study indicated that rates for urban, large rural towns, small rural towns, and isolated rural areas were 15.5%, 13.5%, 22.5% and 17.9% respectively. But the study included other rural issues: more than 60% of these rural women reported four or more events of physical violence compared to 40% of urban women. Another 2015 study also found increased rural risks for IPV: Reviewing 63 studies, the study found prevalence rates were similar across rural, urban, and suburban locales, but also found that certain rural groups (multiracial and separated/divorced women) were noted to be at increased risk for IPV compared to those in urban areas.

Rural Primary Care Providers' DV/IPV Knowledge Gaps

Authors of a December 2017 study looking at rurality and female homicides found that rates increased with access to healthcare professionals: “Results suggest the availability of health care professionals, in rural counties, is associated with an increase in the expected mean intimate femicide rate, not a decrease as we predicted.” The cause of this unexpected result was unclear and the authors postulated several explanations, one related to knowledge gaps: “lack of knowledge may affect identification of risk factors for IPH [intimate partner homicide] by health care professionals, which in turn limits their ability to provide education and support, and effective referrals.”

Experts said providers' knowledge around the complexities of screening and direct patient care for patients experiencing personal violence is critically important. Academic studies show where knowledge gaps exist. Noting that provider knowledge gaps are not just a rural problem, a 2015 extensive worldwide literature review found that “overall, health-care workers remain challenged in screening and appropriately responding to IPV.” Specific to rural providers, a 2013 report surveying 100 rural providers in northeastern New York found respondents lacked information in three areas: IPV prevalence, high injury rates for women leaving abusers, and knowledge around choices made by women experiencing violence. The study also noted a knowledge gap for actionable interventions when violence was disclosed. A 2014 publication based on interviews of 19 practitioners in rural Pennsylvania, “I just keep my antennae out” – How Rural Primary Care Physicians Respond to Intimate Partner Violence, found most providers weren't screening because of training gaps, referral service scarcity, and concern that “inquiry would harm the patient-doctor relationship.”

Focusing on older rural women and IPV, a 2015 analysis of 85 rural Virginia professionals, including 10 medical providers, again noted recurring themes: lack of overall awareness, interventions driven by emergent issues, legally mandated communication, perceptions influenced by community culture, and exclusion from existing professional protocols. An EMT expressed an example of the latter: “Unlike the protocols in place for medical conditions, there is no standardization as to how we proceed. We don't know what to do.”

Experts said it's also important to note patients' perceptions of their providers' recommendations. Though not a study specific to rural patients, this 2012 analysis, “They told me to leave”: How health care providers address intimate partner violence, included interviews with 142 participants and found: “71% felt that their provider wanted them to leave the relationship, with 37.5% reporting being specifically directed to leave.” For participants disclosing IPV to a healthcare provider, the study noted 65% to 85% “felt comfortable and believed their provider to be open or knowledgeable regarding IPV.”

Big Public Health Problem, Big Healthcare Costs

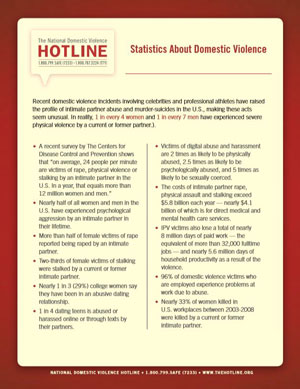

With nearly 12 million women and men experiencing domestic or intimate partner violence (DV or IPV) each year, experts say the economics of the problem can't be overlooked. Specifically addressing rural acute care utilization — known to be a more costly care setting — a September 2017 study looked at 2007 to 2011 data extracted from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Researchers examined nearly 7,400 IPV-related hospitalizations. Over one-third of these admissions were in Appalachia and the highest hospitalization rates were in rural Appalachian counties. But further analysis of non-Appalachian U.S data showed that around 12% of over 4,700 admissions were in rural areas.

The study demonstrated another expensive aspect of IPV-related hospital care: for both urban and rural facilities, the three most common inpatient procedures included the high-cost interventions of alcohol and drug detoxification (a process that can be life-threatening), respiratory intubation and mechanical ventilation (being on a breathing machine requires intensive care), and blood transfusions, the latter which alone can sometimes reach nearly 10% of hospitalization costs.

The research team recognized numerous limitations for their study. They theorized that emergency and inpatient overuse might be related to service shortages in underserved rural Appalachia and have impacted results. But they also highlighted another possible result due to resource scarcity: “Because IPV frequency and severity increases over time, individuals without adequate means to address IPV might remain in situations of escalating abuse that eventually require emergent inpatient care.”

Another look at DV/IPV costs, though not specific to rurality, comes from an Institute for Women's Policy Research August 2017 report (no longer available online). Analyzing a past study that used a decade (1992-2002) of randomly selected female members enrolled in a Pacific Northwest insurance plan, healthcare costs for those experiencing abuse were over 40% higher than the costs for non-abused women. Data in that study also highlighted the issue of the long-term impact of IPV on healthcare costs: for women who reported abuse, even five or more years prior to the study, costs were nearly 20% higher than the control group.

The Institute's researchers also provided a modern cost analysis of a 2004 study looking at 1995 data finding that healthcare and lost productivity totaled $5.8 billion. Broken down: $4.2 billion for physical violence, $320 million for partner rape, and $342 million for partner stalking. Translated into 2017 costs: $9.3 billion.