Aug 23, 2023

RPHWTN Grantees Help Rural Healthcare Facilities Keep Local Talent

by Allee Mead

When Kylie was in high

school, she experienced homelessness. One parent

struggled with substance use and the other was in prison.

Her high school counselor helped connect her to the lead

emergency medical technician (EMT) instructor at a local

college in Missouri. Kylie began taking EMT classes while

finishing high school, receiving both her diploma and her

EMT license.

When Kylie was in high

school, she experienced homelessness. One parent

struggled with substance use and the other was in prison.

Her high school counselor helped connect her to the lead

emergency medical technician (EMT) instructor at a local

college in Missouri. Kylie began taking EMT classes while

finishing high school, receiving both her diploma and her

EMT license.

While Kylie was taking EMT classes, she wasn't able to access healthcare, so the lead EMT instructor connected her with community health workers (CHWs) who helped her sign up for Medicaid. Amber Coleman, Director of Strategy and Innovation with Washington County Ambulance District, helped Kylie get a job as a part-time housekeeper at the ambulance district so she could make some money. Another connection helped Kylie secure a vehicle so she could work and attend classes.

All these connections helped Kylie stay in school, support herself, and find a career path.

Expanding Workforce in Rural Areas

Coleman is part of the Workforce Opportunities for Rural Communities (WORC) project, which helps students like Kylie pursue an education and career that they may not be able to afford or complete otherwise. WORC funds were awarded to Great Mines Health Center, a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), by a Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP) Rural Public Health Workforce Training Network (RPHWTN) grant.

The goal of the RPHWTN program is to expand public health capacity in rural and tribal areas through job development, training, and placement. There are four workforce training tracks: community health support, health information technology (IT) and/or telehealth technical support, community paramedicine, and case management and/or respiratory therapy.

Three grantees — the WORC project in Missouri, a respiratory therapy program in Texas, and a health IT program in Virginia — help students pursue or advance their healthcare careers and support them financially and emotionally. These grantees share stories of changing individuals' lives as well as keeping local talent in their healthcare facilities and communities.

The WORC project serves Iron, Madison, Perry, Reynolds, St. Francois, and Washington counties in the Delta region of Missouri. Doris Boeckman, co-owner of Community Asset Builders, a consultant for WORC, explained that during the pandemic some rural healthcare employees in the region left the profession or took jobs in urban facilities with better pay and benefits.

What we started to realize is if we wanted to build a solid workforce, we were going to have to grow it locally…

“What we started to realize is if we wanted to build a solid workforce, we were going to have to grow it locally, because there are people that live there that want to stay there,” Boeckman said. “And it's easier to do that if you enroll young people and skill them up.”

The WORC program is for students who may not otherwise pursue a two-year or four-year college degree. WORC participants receive financial assistance and connection to any needed resources to complete their training and education. There is a career ladder for participants to become EMTs, CHWs, community paramedics, and nurses. The WORC program also helps students pursue paramedic and CHW certification at the same time.

“We have helped quite a few students receive a certification, licensure — actually find their career path,” Shelby Cox, WORC Project Director, said.

The Lubbock County respiratory therapist program in Texas helps students enroll in a respiratory therapy program at South Plains College. The program partners with nine healthcare facilities, where students will complete clinical training rotations and hopefully work or advance their career someday. These facilities currently have one full-time or a couple part-time respiratory therapists (RTs).

Many people in this part of west Texas have allergies and asthma, and the COVID pandemic contributed to the demand for more RTs. “Healthcare facilities here transfer out the majority of their respiratory patients because they don't have the care or the staff,” Jessica Philpot, Program Director of Rural Health Outreach at University Medical Center (UMC) Health System, said.

In rural southwest Virginia, Mountain Empire Community College (MECC) and the Mountain Empire Rural Health Network (MERHN) used their RPHWTN grant to build workforce capacity in health IT data analytics. Students learn how to build and manage databases and how to use that information to inform a healthcare facility's decision-making. The online program is asynchronous, so students can watch the 10- to 15-minute recorded lectures and complete assignments when they have time.

Nora Blankenbecler, MERHN Health Information Management Director, said many of her health IT students work while taking classes, and some of them are single mothers. “A lot of them say, 'I started in a program and then life got in the way,' which is usually a child,” she said. “But they work in a physician's office or in a hospital or a long-term care facility or somewhere. They may be making $32,000, $38,000 a year, but they have a home, they have childcare, they have all those things and they don't have another partner contributing.” This program can help them advance their career and increase their salary.

Addressing Financial and Other Barriers to Education

In Missouri, WORC pays for costs like transportation, uniforms, tuition fees, textbooks, and equipment like stethoscopes, and WORC staff help with intangible needs as well. For example, the younger students, especially those still in high school, might not have life skills like grocery shopping.

First-generation college students call or text Cox with questions like “What am I supposed to wear to school? Can I wear a hat? What building am I supposed to go to? How do I get my books?”

In Texas, Philpot said program coordinators helped some students set up email accounts. Other challenges for the students include lack of internet access, computers, and desks or study spaces. Lack of internet or unreliable internet connection “ended up being a pretty big barrier for almost everyone,” she said, so program coordinators plan to add a question to application forms about internet access.

I didn't really think I was going to be so much of a counselor or an advisor, but I really had to change my role and be there to help them and walk them through how online programs work.

“I didn't really think I was going to be so much of a counselor or an advisor, but I really had to change my role and be there to help them and walk them through how online programs work,” Philpot said. “I got my master's degree online, so that helped me understand a little bit what they're going through.”

There are currently 27 students enrolled in the RT program, which starts this August. Funds from the RPHWTN grant cover tuition, textbooks, scrubs, and other supplies. Participating healthcare facilities have also drawn up two-year contracts with some students to help cover costs that the RPHWTN grant doesn't cover, like gas, hotel stays, and food while students are completing clinical training rotations.

When South Plains College wanted to open a secondary location in Lubbock, program coordinators helped the college turn an old Air Force base into classrooms, residence halls, and eating facilities. Program coordinators also helped the college create an online curriculum and brought clinical training rotations to students' hometowns so they wouldn't have to drive to Lubbock every day.

When candidates apply, they complete a short essay explaining what a scholarship opportunity would mean to them. Jacob Hilton, Patient Experience Advisor at UMC Health System, remembers warning Philpot about reading candidates' stories “because every one of these stories is going to break your heart…Everyone that applies to this scholarship needs it.”

Success Stories and Community Investment

Hilton feeds all the data collected from student applications — everything from student demographics to how students learned about this program — into a spreadsheet. What he found in studying the data is that the students who were the most successful in the program were not the students with the highest GPA or other academic markers. The most successful students were the ones referred to the program by the local hospital.

“If the hospital that chose them basically said, 'Hey, I know a person and they really need help and I'm sending them over to you,' their success rate is significantly higher,” Hilton said.

The hospital might refer someone who currently works in food and nutrition or in housekeeping or someone in the larger community who could benefit from this educational and employment opportunity. Then, if the student has issues like not having a computer or a place to study, the student can reach back out to the hospital who referred them to help problem-solve.

If the community is invested in that person, that person will be more successful.

“If the community is invested in that person, that person will be more successful,” Hilton said. “You can have a grant all day long, you can have free money all day long, you can advertise the free money all day long, but if the community doesn't invest in that person, they're not going to be successful.”

In Missouri, a nursing student almost had to leave the program because a grant opportunity fell through and she could no longer afford to continue. WORC helped the student find a scholarship that covered her education costs. She recently completed the LPN program and will start the RN program this fall. This nursing student, a mom, is currently working in a catheterization laboratory. “She's already fulfilling a role in healthcare that's very much needed,” Cox said.

Another WORC success story is Leah, a student who began taking EMT classes while she was still in high school. “She already went from a high school student, graduated with her diploma, finished EMT, got her EMT license, and now she's applied for the paramedic program,” Cox said.

Coleman added, “She is very, very close to being able to run a crew by herself.”

WORC started with 13 community partners and now has 18. Partners include healthcare facilities, Mineral Area College, and workforce development boards, among others. Instead of just attending meetings and “checking boxes,” Felisha Richards, Lead Consultant for Community Asset Builders, said, “our partners really focus on those social determinants of health and meeting those needs for the students.”

These partners helped one nursing student get a laptop to take online classes. This student was outside WORC's six-county region, but the partners referred her to someone in her region who could help.

The partners just do whatever the person needs to be successful, because the outcome is benefiting the communities…

“The partners just do whatever the person needs to be successful, because the outcome is benefiting the communities that they have been raised in and continue to work in,” Richards said. “They are invested in the long term too.”

Cox worked with 76 individuals in the first year of the grant. Of these, 58 registered for courses. One student received assistance with testing fees. Of the 58 individuals, 51 completed their coursework: 26 in the EMT program, 12 in the CHW program, 12 in community paramedicine, and 3 in nursing.

For fall 2023, 11 WORC students have been approved for tuition scholarships and another will receive a scholarship to cover EMT testing fees.

In Virginia, Blankenbecler remembers one student who was employed as a clinical analyst for a hospital in Kentucky. She started the health IT program and will graduate this fall. She's found a new job for a leading healthcare organization, is making more money, “and she will be working from home,” Blankenbecler said, “working on implementation projects and using all of the tools that she's learned in the health IT program.”

Blankenbecler said that “we have to demonstrate to our students how they can be cross-functional, how they can work in multiple areas. Like our success story: She started out in coding and she transferred over to clinical data analytics. And now she's in a project management position, managing a huge implementation of an electronic health record over multiple facilities in multiple states.”

Past Challenges and Changes Going Forward

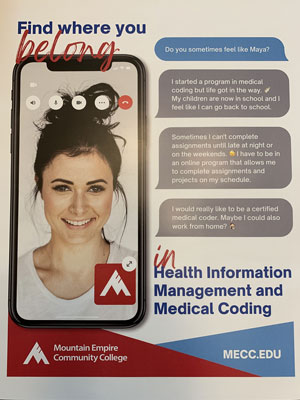

Program coordinators in Virginia completed the first leg of a three-year marketing campaign in which they invented student personas, including one who started a medical coding program but had to quit when she had children; now that her children are in school, she needs a medical coding program with flexibility.

Program coordinators looked through past student surveys to see how they could improve the program or build the marketing campaign. “We sat down with our faculty and we talked about what makes our program work,” Blankenbecler said. “And we wrote everything down on a big board.” One student in a past survey wrote, “I feel like I've found where I belong,” so the marketing campaign includes the statement “Find where you belong.”

Blankenbecler said it's important to build the program and focus the marketing toward students' needs: “They're telling you all along what they need, but you just have to make sure that you're paying attention and you're listening to that.” Having students share their stories may also resonate with a future student.

They're telling you all along what they need, but you just have to make sure that you're paying attention and you're listening to that.

In Texas, Hilton makes sure that all questions on the scholarship applications are written simply and in plain language and that the applicants' personal stories wouldn't be evaluated based on grammar or spelling. “I don't want this to be the thing that prevents them from being able to apply,” he said.

Program coordinators also ask if students have completed any prerequisite courses. “It doesn't count for or against them,” Hilton said. “If you have completed a lot of your prerequisites before you go to the university, we can put you in a different cohort in the program.”

Program coordinators choose scholarship candidates from each county in the program's service area. In the event of a tie between applicants, the hospital where students would be doing their clinical training rotations weighs in on choosing a scholarship recipient.

In Missouri, Cox said that turnover within the WORC partner organizations can be a challenge, when WORC program coordinators have to re-explain what they do and how their work can benefit these partners. It's important to communicate their work because these partners are “the cheerleaders for the grant,” she said. “They know the high school counselors, they know the volunteer fire departments, they know the hospitals and the ambulance services.”

In addition, WORC partners with workforce development boards. “They can assist students with scholarships too,” she said. “They can assist with some of those wraparound services. They can help assess skill levels and help direct students to the program.” Boeckman also recommended finding champions and building relationships early.

One early challenge for the WORC project was that students had to travel to Pettis County for the CHW program, since the local college was not a registered provider of that curriculum. “There are standards for the curriculum, but the curriculum itself had to be developed,” Boeckman explained. “And we developed that in less than six months.”

“It's been quite remarkable, the things that we've accomplished in such a short time with this grant,” Cox said.