Dec 18, 2019

Understanding Rural Health Departments: Do They Have Unique Accreditation Needs?

Related Articles

It's

Possible: Voluntary Accreditation for Rural Public Health

Departments

Taney

County Health Department: Accreditation and Holding to a

Higher Standard

Public health accreditation is becoming increasingly widespread, with over 75 rural local health departments (RLHDs) reaching accreditation as of November 2019. Researchers and experts said it's important to understand that factors ranging from governing oversight to size impact a RLHD's decision to attempt accreditation.

Governance is the support of a department's governing body. The Public Health Accreditation Board's (PHAB) initial accreditation preparation checklist formally includes the question: “Does the appointing authority for the health department director (the person with the authority to hire the director of the health department) support the health department's seeking PHAB accreditation?”

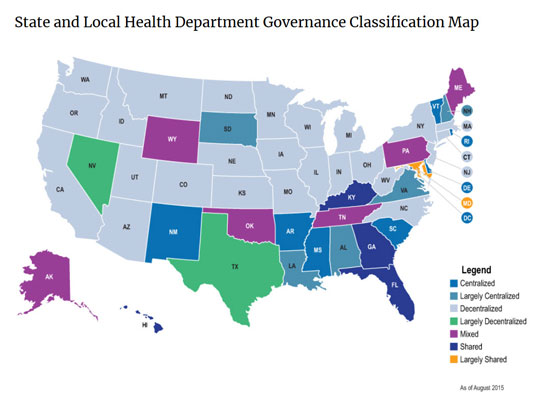

So who governs, or oversees, RLHDs? The answer? It varies. A 2012 report from the NORC Walsh Center and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) reviews the variety of operational dynamics between state and local health departments. Currently described as centralized, decentralized, shared, or mixed, these terms refer to the patterns that represent the relationships between state and local public health agencies. For example, especially in the western United States, many departments are decentralized, meaning that a local board of health (LBOH) or a county-level authority has oversight, in contrast to more populous states where a larger state health department provides direction to the smaller departments. Other areas of the country have a mix of centralized, largely centralized, or mixed oversight. Because of the strategic importance of oversight in the daily activities of a health department, Dr. Kaye Bender, President and CEO of PHAB, pointed out that several of PHAB's national accreditation program domains specifically include governance. For example, domain 11 includes attention on how a PHD is run, its budgets, audit processes, information technology use, and human resource work. Domain 12 further addresses PHD activities around the interaction of a department with its governing entity, whether that is the governor, the mayor, county commissioners or board of supervisors, or a local board of health. Acknowledging that local governing boards play a part in a RLHD's decision to take on the accreditation process, Bender also reviewed some of the decisions behind several state-led initiatives for accreditation.

“North Carolina and Michigan had state-driven mandatory accreditation before the existence of PHAB,” Bender said. “Missouri has their own voluntary accreditation program. After we launched accreditation, Florida requested a process that could include every department in the state since they function as one department with state policies and procedures that the local departments can tweak. Theirs is essentially a system with benefits for smaller departments since they are all officially working closely with the larger departments. We were able to accommodate that request, though the state department of health had to be accredited first.”

Bender also pointed out that Ohio ― as part of their statewide movement referred to as the Ohio Health Modernization Movement ― went with a mandatory accreditation approach using PHAB's process as part of that approach. Among the pathways recommended by the state is that smaller departments considering accreditation could choose joining other jurisdictions to form a single operating unit. Some experts pointed out that this is a type of “cross-jurisdictional sharing” often seen in many other areas of the country. Locations employing this approach are shown in an interactive map created by the Center for Sharing Public Health Services.

Cross-jurisdictional sharing, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is “a growing strategy used by state, tribal, local, and territorial agencies and organizations to address opportunities and challenges such as tight budgets, increased burden of disease, and regional planning needs.” Experts also said they believe that this approach might be especially helpful for a RLHD's accreditation efforts.

In addition to the accreditation activities in these five states, Minnesota's Department of Health has announced that by 2020, “100% of community health boards will be prepared to apply for accreditation.” Kentucky, too, is a state with a large number of RLHDs working on accreditation in a collaborative fashion, many with the assistance of the University of Kentucky College of Public Health.

But without a state-level movement or support from a public health school, accreditation can be daunting for RLHDs. Bender said that PHAB and other organizations want to make sure they are attending to the accreditation needs of the smaller health departments, which includes RLHDs.

“We don't use rurality as a measure of small,” Bender said. “We look at size. We know that there are a number of small health departments that will continue to shy away from accreditation. We are committed to making sure we fully understand the needs, struggles, and strengths of those departments so we can hopefully provide further assistance in their desire to be accredited.”

Bender shared that this commitment is now actualized by the formation of a Joint Task Force on Small Department Accreditation. In addition to PHAB board representation, members serving on the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) board will work to accomplish several goals, three of which are:

- Creating a working definition of a small health department for accreditation purposes

- Improving the knowledge around small health departments' profiles: for example, population served, services provided, staff numbers, budgets

- Better understanding of small health departments' facilitators and barriers around accreditation activities

Bender also said that in addition to the task force, a commissioned research paper will examine the accreditation successes of the most rural of the small departments.

“We anticipate this work will be completed by Spring 2020,” Bender said. “We certainly look forward to learning how we can improve the current accreditation program in order to reach a little deeper into the smaller, more rural departments.”

In addition to PHAB and NACCHO, another organization is examining the needs of small rural health departments: the de Beaumont Foundation. Dr. Katie Sellers, public health researcher and de Beaumont's Vice President of Impact, shared the Foundation's philosophy and how that intersects with the work of public health departments.

“We believe that advocating for policies that promote health is an effective and efficient way to make sustainable change in the health of Americans, including those in rural America,” Sellers said. “Public health's emphasis on health equity means we need to focus on populations that are most in need and find out what those populations require and want for themselves. Rural communities need to be included.”

Sellers explained that the Foundation, in partnership with ASTHO, conducts a public health workforce survey called PH WINS, the Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey. For the two previous administrations of the survey, Sellers explained that they've used the threshold of health departments with at least 25 employees or serving a population of at least 25,000. However, in the 2020 administration of the survey, PH WINS will work with several of the Regional Public Health Training Centers that are funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to test the inclusion of smaller local health departments in some states.

“This survey will include every health department in some selected states,” Sellers said. “That will allow us to compare results from the very small health departments. We'll be able to see if their workplace environment is different. It will also help those regional public health training centers that are involved in this pilot to do a better job of serving those smaller health departments.”