Dec 18, 2019

It's Possible: Voluntary Accreditation for Rural Public Health Departments

Related Articles

Understanding

Rural Health Departments: Do They Have Unique

Accreditation Needs?

Taney

County Health Department: Accreditation and Holding to a

Higher Standard

Public health. Two six-letter words

that describe two enormous actions: protecting and

improving the health and well-being of the nation's

citizens. For public health professionals,

attention to the work itself is not the

intention of their work since they understand

the work's paradox: when their work is done well, it is

work that draws little attention. To maintain that work

at the highest standard, public health professionals need

an opportunity that can provide their organizations with

a process to assess the excellence of their work.

Voluntary accreditation is one way the nation's health

departments ― including rural local health departments

(RLHDs) ― can measure themselves against a universal

standard of excellence.

Public health. Two six-letter words

that describe two enormous actions: protecting and

improving the health and well-being of the nation's

citizens. For public health professionals,

attention to the work itself is not the

intention of their work since they understand

the work's paradox: when their work is done well, it is

work that draws little attention. To maintain that work

at the highest standard, public health professionals need

an opportunity that can provide their organizations with

a process to assess the excellence of their work.

Voluntary accreditation is one way the nation's health

departments ― including rural local health departments

(RLHDs) ― can measure themselves against a universal

standard of excellence.

What defines public health work?

The CDC Foundation describes public health work as dedicated to “promoting healthy lifestyles, researching disease and injury prevention, and detecting, preventing and responding to infectious diseases.”

Liza Corso is a senior advisor for Public Health Practice and Accreditation at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) Center for State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Support (CSTLTS), the center that “plays a vital role in helping health agencies work to enhance their capacity and improve their performance to strengthen the public health system on all levels.” Prior to coming to the CDC, Corso was involved with public health standards development and worked with health departments in strengthening infrastructure, including efforts targeted for small and rural HDs, in conducting and using community health needs assessments. At the CDC, where she has been since 2002, she continues to do work involving rural, tribal, and territorial public health jurisdictions, including leading CDC's support for accreditation.

“CSTLTS seeks to support health departments of all types and structures. In fact, within CSTLTS, we have the Office of Tribal Affairs and Strategic Alliances and the Office of Insular Affairs so our assistance can especially meet the unique needs of tribes and territories,” Corso said, sharing that accreditation is one of the potential needs. “Accreditation can play a key role in strengthening health departments and the services they provide. Just as the public expects their hospitals and their schools to be accredited, we hope one day the public can expect that of their health departments. One of the old adages that CDC sees as aligned with public health accreditation work is that accreditation can help health departments 'do the right things and do things right.'”

Accreditation Differences: Healthcare Institutions versus Public Health Agencies

Accreditation is a routine process in many professions and industries. There are several reasons healthcare institutions in particular seek accreditation. It is often perceived as reflective of an organization's willingness to exceed usual performance expectations; it is linked to certain Medicare and Medicaid clinic service reimbursement; and through a deeming authority, it is sometimes mandatory as part of state licensure. As Corso pointed out, since public health organizations exist in an environment with these accreditated healthcare providers, it might be of no surprise that accreditation is emerging as a voluntary goal of many health departments, regardless of size and population served.

Because the accreditation needs of clinical facilities and public health departments (PHDs) are not the same, understanding the similarities and differences of their accreditation processes is important. Both have a set of national standards. Just as with clinical accreditation, quality improvement (QI) work is vital to achieving PHD accreditation. However, clinical and public health QI activities do differ. The latter, according to the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), uses QI focused on overall population health and as a way to “achieve efficiencies and improve quality of services to improve overall community health” versus clinical QI activities, which often focus on an institution's policies and procedures.

Dr. Kaye Bender is President and CEO of the Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB). The organization was incorporated in 2007 and the first PHDs were accredited in 2013. A national leader assisting in the work that culminated in the current PHD accreditation standards, Bender had a career start as a registered nurse in Mississippi doing maternal and child clinical work in labor, delivery, and neonatal intensive care. She said these experiences gave her a perspective that allowed a better understanding of how public health department accreditation standards would need to differ from those of clinical institutions.

“The whole goal of accreditation is to give health departments a standardized process whereby they can compare themselves against national standards and be able to figure out how they can do things better,” Bender said. “Everything is based on quality improvement. Though hospitals had been talking about improving the quality of care for a long time, at the time we launched this work, it was a new concept for public health. To apply the principles from healthcare to public health necessitated a new body of work that happened in parallel with the creation of PHAB.”

Bender shared that the consensus-based accreditation standards came from the collaborative work of nearly 4,000 public health practitioners from think tanks, expert panels, committees, and surveys. She said the final standards were also the result of “much consultation with those in the field and not only reflect current practice, but include a 'stretch' towards future practice.”

As a member of the committee that produced the 2002 landmark public health report, The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century, Bender said the accreditation work that followed was never intended to be regulatory in nature.

“We remind ourselves all the time that we never intend to be regulatory,” she said. “Of course, there's a place for regulations, but this is not it. We created a rigorous process that was in line with other accreditation programs and has similar-looking steps. But we talk about being in conformity with our standards rather than being in compliance.”

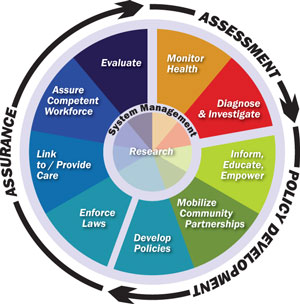

Core to the Accreditation Process: Aligning Domains with Essential Services

Accreditation requires that public health departments look closely at their daily work, described as having three core functions: assessment, policy development, and assurance. These functions are further categorized into specific activities, referred to as the 10 essential services, a list that has guided public health work since 1994. The accreditation process aligns these services, but uses a different naming system, or taxonomy. PHAB's structural framework aligns with a specific service, but refers to that service area as a domain. For each domain, there is a set of grouped standards and for each standard are measures that require documentation (Table 1). For example, domain 5 is centered in public health policy and plan development. One standard for that domain, noted as 5.4, is the all hazards emergency plan. A measure required for that domain standard will include the process for that emergency plan and the required documentation might include meeting minutes of collaborative planning session with other government agencies, like law enforcement.

| Table 1. Comparison of Public Health Essential Services and Accreditation Domains | ||

| Core Function | 10 Essential Public Health Services | 12 Accreditation Domains |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Monitor health | Conduct and disseminate community health assessments |

| Diagnose and investigate | Investigate community health and environmental issues | |

| Policy Development | Inform, educate, and empower | Inform and educate |

| Mobilize community partnerships | Community engagement to obtain community perspective | |

| Develop policies | Develop public health policies and plans | |

| Assurance | Enforce laws | Enforce public health laws |

| Link to care and provide care | Promote strategies to improve access to healthcare services | |

| Workforce competency | Maintenance of competent workforce | |

| Evaluate | Continuous improvement for processes, programs, interventions | |

| Research | Use/Contribute to the public health evidence base | |

| Maintain administrative and management capacity | ||

| Maintain public health governing entity engagement | ||

In order to understand how the accreditation process might work for RLHDs, experts and researchers said it's important to also understand the differences in the nature of services provided by rural and urban health departments, as described through the essential services (Table 2). Michael Meit, co-director of the NORC Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis, has long studied rural public health issues, including accreditation, and has specifically investigated the work of the RLHDs. Meit explained that one key area of difference between urban and rural health departments is the relative focus on clinical versus population health services. Because accreditation is focused on population health services as opposed to clinical services, many RLHDs may not provide a full array of services necessary to seek voluntary accreditation.

“When you go back into the history of public health, a lot of it was clinical work, like tuberculosis control, immunizations, and similar type of care,” Meit said. “While specific clinical services shifted over time, many health departments continue to provide vaccination services as well as other primary care-type services, like breast and cervical cancer screening, or STI [sexually transmitted infection] testing and screening. At the same time, as the factors that influence our health status have shifted, so has the work of public health. Specifically, urban and larger health departments have moved away from clinical services towards a population health focus. This shift works in many urban health departments because there are plenty of other organizations that fulfill those clinical roles. But in rural areas, where the provider shortages are greater, the health departments will do some of the population health work, but at the same time, have often needed to maintain many of those clinical services.”

Service Differences Between Rural and Urban Local Health Departments

As Meit mentioned, rurality influences the work of local public health departments. A 2016 National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) report outlined services most likely provided by rural and urban health departments.

| Table 2. 2016 NACCHO National Profile of Local Health Departments | |||||

| Rural | Urban | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Programs and services more likely to be provided by rural LHDs |

% Rural LHDs |

% Urban LHDs |

Programs and services more likely to be provided by urban LHDs |

% Urban LDHs |

% Rural LHDs |

| Childhood immunizations | 95 | 77 | Food establishment regulation | 91 | 61 |

| Maternal and child health surveillance | 75 | 59 | Recreational water regulation | 82 | 45 |

| Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program | 72 | 53 | Schools/daycare regulation | 81 | 59 |

| Blood lead screening | 72 | 49 | Septic system regulation | 75 | 55 |

| Body mass index screening | 65 | 43 | Children's camps regulation | 70 | 40 |

| Maternal and child health home visits | 64 | 51 | Body art retailer regulation | 66 | 44 |

| High blood pressure screening | 62 | 51 | Lead inspection | 63 | 40 |

| Family planning | 56 | 42 | Housing inspection | 45 | 15 |

| School-based clinics | 50 | 24 | Indoor air quality control | 44 | 23 |

| School health | 49 | 36 | Noise pollution control | 31 | 6 |

| Early and periodic screening, diagnosis, and treatment (EPSDT) | 42 | 27 | Air pollution control | 30 | 10 |

| Home health care | 32 | 11 | |||

| Note: Suburban health departments are not represented. | |||||

Considering Accreditation? Tips, How-to's and Other Considerations

Despite challenges, many rural health departments have achieved accreditation. As of November 2019, the Public Health Accreditation Board website listed over 75 accredited health departments that are in locations that meet a rural designation.

Kim McCoy, a senior program manager at Minnesota-based Stratis Health, has been involved in public health department activities for many years with a focus that includes capacity building, community health assessment work, and quality improvement activities. Having assisted health departments large and small, she serves as a volunteer accreditation site visitor. McCoy said she believes that accreditation activities and standards may actually be more doable in rural areas compared to large urban departments.

“If health departments are concerned that they might be too rural or too small or are worried about lack of resources to accomplish accreditation, they should consider that accreditation might be easier for them because they know their community and their community partners so well,” she said. “Rural communities have a track record of working together. Having that smaller group of partners sometimes makes collaboration easier, resulting in a higher number of successful collaborative efforts that meet the measures of accreditation.”

McCoy also said that although familiarity with partners can be a benefit, care has to be given to document those strong relationships. Documentation requirements for the standards and measures should be closely reviewed, especially for any item noted as a “must,” an important accreditation element.

Another tip McCoy mentioned was the importance of reading through the entire list of requirements followed by a reflection on the accreditation requirements.

“Read through the requirements, but then step back and look at them as a whole,” she said. “Many health departments are doing work that matches accreditation measures. Sometimes there's not just one specific action that meets a standard, so don't overthink the standard. Think about what you're already doing that might meet that standard or measure.”

In addition to her suggestion of a read-through followed by reflection, McCoy suggested to connect with other RLHDs that have been accredited. Dr. Angela Carman, an assistant professor at the University of Kentucky College of Public Health, echoed both of McCoy's suggestions. Carman and her colleagues formally offer the latter in a recent publication that collated information gathered from 12 small and rural health departments that were accredited or accreditation-ready. The article shared the various departments' approaches to the accreditation process. In common, of course, was resource scarcity. Shared experiences were grounded in a central statement: Knowing what you know now about accreditation, describe what you would do differently with your accreditation-readiness process.

“One of the main learnings was that just because the accreditation domains were numbered, there was no need to address them in numerical order,” Carman said. “Domain 2 is not of greater priority than domain 11. It's important to read through all of the measures and while doing that reading, identify connections between the domains and measures according to the 10 essential public health services.”

Carman also emphasized that prep work should focus on the intent of the measures. She said that the intent of accreditation is to show that the department had planned, collaborated, and is efficient in its use of resources. She pointed out that focusing on intent often further reveals a department activity that is labeled by another name, but is exactly the activity required by the standard ― a “labeling and packaging” sort of discovery.

“Most importantly, always remember that accreditation is based in quality improvement,” she said. “Show what is being done and how it's going to be done better. It becomes your daily work of doing business.”

Words From Critical Access Hospital CEO Turned Rural Public Health Researcher

Like PHAB's president Bender, as CEO of one of Kentucky's Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs), Carman was associated with the clinical care of patients during her pre-doctoral years. She said she now has some clarity around several missed opportunities she had as a CEO to partner with an RLHD.

“When I was the CEO of a CAH, I knew we had a health department, but we never worked on something together,” she said. “Now that I've left that role and have come to this side of the fence doing public health work focused on accreditation, I realize how valuable that relationship could have been. Your health department is an expert in prevention. Because they are experts in prevention, they are trying to assist those patients who are continually coming back to the hospital and can be extremely valuable in being sure that your resources as a healthcare entity are used properly.”

Carman identified a second missed opportunity: community needs assessment, an integral part of the PHD work and the accreditation process — and under the Affordable Care Act, an assessment that nonprofit hospitals must also perform in order to maintain their nonprofit status.

“Your local health department is a convener of community stakeholders and is one of the main elements in a community's public health system,” she said. “They're used to bringing people together. They know how important it is to hear the voice of the hospital and the school and all the other nonprofit agencies that are working in the community with different target audiences. They can help hospitals get that full picture of what's going on in the community. Get to know them. Learn where their expertise is. Connect whenever you possibly can. It will better your community.”

Avoiding Stigma: Balancing Community Public Health Needs with Accreditation Requirements

Dr. Kate Beatty, Interim Director of Research, Center for Rural Health Research at East Tennessee State University College of Public Health, has also studied RLHDs. Building on NORC co-director Meit's comments regarding the clinical services provided by these organizations, she said when a RLHD offers more clinical services and less of the other essential services, an accreditation barrier can result. But she believes that pulling out of those clinical services might leave a community vulnerable.

“Our research indicates that the amount of clinical services offered by a health department does influence the choice of pursuing accreditation,” Beatty said. “In my opinion, for those small and rural public health departments, I think there'd be some ethical implications if they're the only provider doing clinical care and found they had to eliminate that work in order to seek accreditation. Stepping back and considering that the clinical care done by the rural health department is actually meeting the needs of their community — what public health work is meant to do — you have to think about this in the face of accreditation.”

In a recent study, Beatty, Meit, and other researchers investigated issues that influence whether a RLHD will seek accreditation. They found that barriers can include such factors as a governing board that declines to approve the effort. Other pushbacks include fees, lack of staffing, as well as a concern that the accreditation standards include domains that are not addressed by their specific work. Beatty suggested that for any research that goes forward in this space, it's important not to stigmatize those RLHDs that haven't visualized how accreditation might fit for them.

“There are a lot of health departments ― especially in rural communities ― that don't have the capacity to go through accreditation,” she said. “Through my field experiences, I've seen that there are great health departments doing great work, but they're just unable to attempt accreditation. However, they are very connected to their communities and to their community partners. They know what they can do, they've identified what they need to do. It's important to not stigmatize those departments as a low-functioning health department just because they are unable to take on accreditation at this time.”

Actively Attending to Accreditation Equity

The issues Beatty raises have the attention of many organizations. In order that accreditation be attainable for all public health departments ― despite size or number of provided essential services ― PHAB and NACCHO are leading the effort to further understand the accreditation needs of smaller health departments.

The Unseen, Unmeasured, and Intangible Side of Accreditation

Since the first accreditation awards were conferred in 2013, there have been anecdotal RLHD reports of many of the unseen, unmeasured, and intangible benefits attached to either accreditation achievement or even just having considered accreditation. With reference to that latter group, experts and researchers said there are many positive stories from RLHDs that by accessing PHAB's accreditation standards, measures, and processes, departments have bettered their work in many ways.

For those who have achieved accreditation, those departments can now go to their governing bodies and show proof of a job well done. In addition, they report a sense of increased stature when meeting with community partners who have also been accredited by their respective professional bodies. Experts said that very frequent are the stories of not just an individual department worker's professional growth, but an associated personal growth from having met accreditation challenges. PHAB's Bender confirms these informal reports.

“Even here at PHAB we continually have to have our own external evaluation on accreditation benefits,” Bender said. “That external validity is important. The most frequent feedback we receive from health departments concerns the impact provided by the external validation that results from accreditation. It allows them to say with pride to their communities, their state legislatures, their governing boards, 'Our work meets national accreditation standards.'”

Resources

Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO)

Center for State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Support (CSTLTS)

National Association of County & City Health Officials (NACCHO)

Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB)