May 02, 2018

Rural Post-Acute Care: Improving Transitions to Enhance Patient Recovery

by Jenn Lukens

This is the first in a two-part series on rural post-acute care. Read part two – Rural Post-Acute Care: Healthcare Leaders Offer Practical Solutions to Workforce Challenges

At the time of a hospital discharge, a patient may not be ready to return home without further care and medical assistance. Finding local post-acute care (PAC) can make fully recovering from a serious illness or injury faster and easier for both patient and family, while lessening the likelihood of a hospital readmission.

The transition between a hospital and PAC can carry a lot of weight regarding a patient's recovery. When key information about his or her condition, changes in health, and medication are overlooked or forgotten, the patient's safety and recovery progress may be compromised. When done thoroughly, transitions are well coordinated and intentional, setting both the patient and provider up for the best possible outcome.

Who Provides Post-Acute Care in Rural Areas?

In rural communities, PAC services are most often provided by skilled nursing facilities, home health services, or hospitals' swing bed programs. The points below outline some of the key differences between each of them:

Swing Bed Programs

- Located in small, rural hospitals, allowing physicians easy access to continue treating their patient.

- Allow the hospital to use its beds to provide either acute or skilled nursing care.

- “Swing” refers to the hospital's ability to provide two levels of care for patients while keeping them in the same bed.

Skilled Nursing Facilities

- A facility or separate unit within a facility, such as a nursing home or hospital, that accepts transfers from a hospital.

- Provide an intermediate level of short-term skilled nursing and rehabilitation services.

- The most utilized and common type of PAC service in rural America.

Home Health Services

- Healthcare services for homebound patients ordered by a doctor.

- An enrolled patient is under the medical care of a doctor who regularly reviews their medical plan.

- Provides intermittent skilled nursing care as well as physical, occupational, and speech therapy, among other services.

- Can be provided by a public entity (state or local government), or by a nonprofit or for-profit organization (healthcare system or independent agency).

IMPACTing the INTERACTion: Improving Communication Between Discharge Hospital and Skilled Nursing Facilities

Carole Bartoo, AGPCNP-BC, works as a transition advocate at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) Center for Quality Aging in Nashville. Bartoo was part of an effort to improve transitions of acute Medicare patients to 23 partnering skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). Located throughout Tennessee and Kentucky, 12 of them are in rural communities. She also works part time at a local SNF and understands what it's like on the transfer's receiving end. “It can vary quite a bit. There are certainly times you feel lucky if you get any information about what happened to the patient while they were in the hospital, much less how they may differ from their baseline,” said Bartoo. With few federal mandates regarding processes and requirements, PAC services are often left to figure things out as they go along.

To help standardize the discharge process, Dr. John Schnelle, Hamilton Chair of Geriatrics and Director of the Center for Quality Aging at VUMC, led a study to improve documentation of their patient's acute care course.

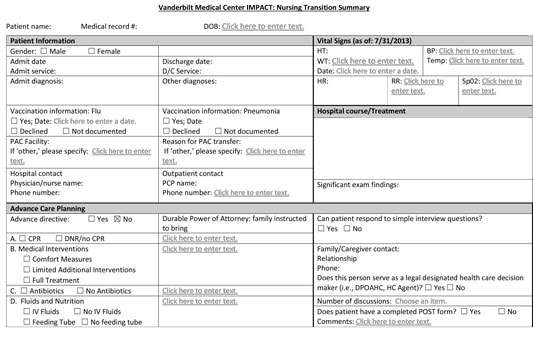

Information including complications, new symptoms and syndromes, and medication changes were compiled by the Improved Post-Acute Care Transitions (IMPACT) team, of which Bartoo was a part. She and other transition advocates worked closely with VUMC pharmacists to document medication changes and with clinicians to record the patients' progress. They then compiled information into a Nursing Transition Summary (NuTS) which was shared at the time of discharge with the SNFs' admitting nurses.

Each partnering SNF was trained in the use of the Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) tool. Designed to help SNF staff recognize early changes in a newly-received patient, INTERACT also outlines suggested care pathways. IMPACT and INTERACT were tools adapted from Pathway Health and used in an effort to also help reduce unnecessary hospital readmissions.

PAC Transition Tool #1: Documentation of Patient Progress

Below is a sample (page 1 of 5) of part of the VUMC NuTS form used by transition advocates to improve documentation of a patient's progress. This form was adapted from various INTERACT tools that be downloaded for free from Pathway Health.

“Every hospital in the country has a real challenge to find a way to improve the quality of transitions. Our job was to try to, in a rich way, give nursing facilities the information they needed to keep lingering health concerns from becoming a problem,” explained Bartoo.

Dr. Alana Knudson, Project Area Director and Co-Director of the Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis at NORC, commends these kinds of intentional efforts: “A lot of acute care takes place in a tertiary facility, so good communication between a tertiary facility and rural providers is key.”

In an analysis of the VUMC program, Knudson's team found that, while there was no large statistical difference in 30-day hospital readmissions, Vanderbilt's emergency department visits did decrease (-70 per 1,000 beneficiary episodes per quarter).

Transitional Care Team Works Together to Smooth Transitions

The swing bed program offers another PAC choice for patients. Enacted in 1980 for small, rural hospitals, it not only helped those struggling with decreasing inpatient admissions but also relieved nursing homes experiencing ever-growing wait lists. Nearly all (96%) Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) provide PAC services, with swing bed being the most common.

The swing bed program at Nebraska's Lexington Regional Health Center (LRHC) has become an integral part of their PAC services, allowing patients access to care and services close to home while recovering from an acute illness or injury. Patients can stay under the careful watch of their physician, not noticing much of a difference from the care they received as an acute patient. “In terms of actual care provision, nothing really changes, and that's the beauty of a swing bed,” said Leslie Marsh, RN, BS, MSN, MBA and CEO of LRHC.

One of Marsh's first initiatives after joining LRHC in 2010 was developing a transitional care team. Inspired by other evidence-based models and developed as a group effort, the team is made up of healthcare professionals from 10 different disciplines. They all work together with the patient throughout their transitional and PAC process. Patients transitioning to swing bed status undergo a stratified risk assessment using a tool developed in-house, and a recovery plan is established. Morning “hospital huddles” allow for quick briefings with the transitional care team and hospitalists, as well as provide an opportunity to make updates to the discharge plan.

Outpatient services like mental healthcare, cardiac rehab, nutrition counseling, diabetic education, and wellness coaching are offered as post-discharge services to help prevent hospital readmissions.

LRHC uses this team-based transition approach for all patients being discharged from any one of their services. Medical patients are generally discharged within 14 days, and post-orthopedic surgical patients are released within two. Some PAC patients have beaten the odds, which was the case for one man who broke both of his arms and legs in a devastating motor vehicle accident. Expected to be in the hospital for two months, he was discharged just three weeks later after some time in the swing bed program.

The transitional care model is also having effects on LRHC's readmission rates: in the past few years, they have decreased by 82%. According to Marsh, the time put in to ensuring successful transitions is paying off. Improved care coordination and quality of care for PAC patients is resulting in less time spent in a PAC setting, ultimately reducing healthcare spending.

LRHC's transitional care process has received high patient satisfaction ratings and recognition from the Nebraska Hospital Association, the American Hospital Association, the Studer Group, and other rural health experts across the nation. LRHC was also selected to be a participant in a study run by the University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center which was designed to examine the need for, and potential challenges related to, a common set of swing bed quality metrics.

We all know that people's healthcare needs can change, meaning their plans may change. Understanding this dynamic, LRHC's team is constantly reevaluating with the patient, their goals, and the need to readdress plans as needed. The defining characteristic is that, truly, it's about the patient.

With every patient care plan, the transitional care team understands the need to remain flexible. “We all know that people's healthcare needs can change, meaning their plans may change. Understanding this dynamic, LRHC's team is constantly reevaluating with the patient, their goals, and the need to readdress plans as needed,” said Marsh. “The defining characteristic is that, truly, it's about the patient. We all want to work together to make sure that the patient gets the best care.”

This video produced by the Nebraska Hospital Association goes into more detail about LRHC's transitional care process:

Be Our Guest: Home Health Service Cares for Patients in the Comfort of Their Own Homes

Home health, as the name suggests, is healthcare delivered to homebound patients who are well enough to be out of the healthcare setting, but not well enough to take care of themselves. Since rural residents have a higher prevalence of risk factors for hospitalization, transitioning patients to a home health service for PAC can help monitor these risk factors in a more comfortable setting.

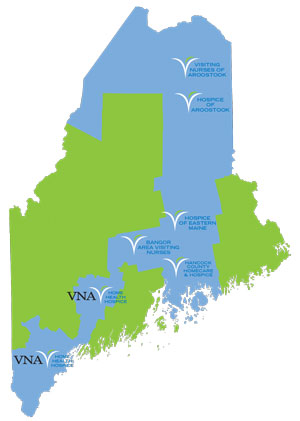

A member organization of Eastern Maine Healthcare Systems (EMHS), VNA Home Health Hospice serves urban populations in southern Maine and rural population in the northern region. VNA clinicians make 160,000 in-home visits each year with 1,400 patients under their care on an average daily basis. VNA participated in a recent study conducted by the Rural Health Reform Policy Research Center, led by Dr. Alana Knudson, which found that “strong relationships between rural home health agencies and local hospitals are fundamental to improving patient outcomes.”

Being a member of a large health system, VNA gets a close-up view of each community they serve, as well as quick access to medical professionals concerning their patients' needs. In turn, EMHS gains an insider's perspective of the conditions influencing a patient's recovery and the success of a transition.

“I think it's a unique role that we have, being guests in people's homes. We see a lot that other healthcare providers don't necessarily see,” said Elizabeth Rolfe, RN, NE-BC, and Vice President of Nursing and Patient Care Services at VNA. “We have sometimes been the first people to discover that the patient who keeps showing up in the ER and getting admitted is the person living in a home with a dirt floor, or they're a hoarder and they can't get into their bathroom anymore.”

A patient's transition to VNA's home health program begins with a referral from a provider or an inpatient facility within or outside of EMHS. Prior to the transition, the provider fills out a request for services the home health nurses provide once a patient is transitioned, including medication review and distribution, monitoring vital signs, and wound care. An evaluation of the patient helps determine which additional home health services will best meet their medical needs.

As part of an integrated health system, VNA works in close collaboration with EMHS's Accountable Care Organization (ACO) population healthcare managers, in-patient care managers, and specialty providers to ensure safe transitions. The two groups have monthly meetings to review gaps and improvement opportunities in the transition process. VNA also participates in evaluations and care management meetings for high-risk patients in order to best meet their needs during the transition.

Rolfe advises hospital providers to ease the transition process by reassuring patients that they will be placed into the hands of excellent staff who will care for the same concerns, care needs, and goals that have been addressed in the hospital setting.

“Going home after an episode of illness can indeed be a frightening experience. The entire care management team can make that process less stressful through clear transitional communication, with each member of the team laying the foundation for the next care team that will follow them,” said Rolfe.

Reducing Medications to Lighten the Load for PAC Services and Patients

When you are transitioning someone to another environment on Friday afternoon, the last thing you are thinking about is if they have enough medication to get through the weekend.

Once the patient is discharged to a PAC facility or to their home, many problems that surface can be tied to medication management. Knudson's own experience transitioning her parents and grandparents back to their rural communities from acute care have made this reality personal: “When you are transitioning someone to another environment on Friday afternoon, the last thing you are thinking about is if they have enough medication to get through the weekend.” Less frequently-prescribed medications may not be on-hand at the local rural pharmacy and may take several days to be delivered.

VNA's hospital avoidance program requires home health clinicians to communicate with the discharging facility about the patient's medication, as well as other challenges the patient has faced while in the hospital. Protocols VNA has established with discharging facilities allow patients to undergo certain medical interventions through home health, including medication changes, without having to go back to a hospital.

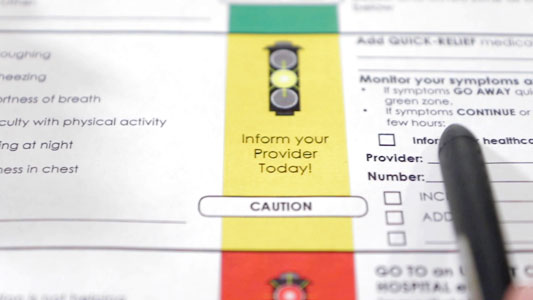

When a patient is getting closer to being discharged from Lexington Regional Health Center, education and action plans are streamlined so that every hospitalized patient gets the same information from all directions. A care coordinator works with the primary care nurse so that the importance and purpose of each medication is repeatedly reviewed with the patient and caregivers. Action plans are reviewed and the patient receives a “stop light report” which compares the severity of developing symptoms to traffic light signals for daily self-regulation. Two days after discharge, the transitional care team director visits the patient at their home to make sure they are on-track with the mediation regimen.

PAC Transition Tool #2: Education for Self-Regulation

When discharged, LRHC gives a patient this stop light

report to help determine when to seek medical help,

comparing the severity of developing symptoms to

traffic signals:

Schnelle's colleagues at Vanderbilt are trying to smooth this process by reducing the number of medications Medicare beneficiaries take at the time of discharge. Influenced by the IMPACT study, Shed-Meds is an ongoing study of the effects of reducing polypharmacy (taking 5 or more medications). Through the new project, VUMC is showing how beneficial it is to simply talk with the patient about their medications.

“You'd be surprised – if you have a conversation like this with an older person, quite frequently, they don't know why they are taking something. They just do it because they have for a long time and no one told them not to,” said Schnelle. “By having these conversations, we believe we can reduce the amount of medication, and we think it's going to improve transitions when that happens.”

Although medication management and appropriate patient education takes time, Schnelle says that it's hard to argue why someone shouldn't do it: “You will definitely get a reduction of how many medications the patient is taking. Although it might cost a hospital because of the conversation, think of the cost savings to the patient.” The benefits are three-fold: cost savings for patient, improved health in the long-run, and less to manage for the PAC service.

The Driving Factor: A Patient's Right to Choose

Several factors play a role in determining the best PAC service for a patient, including service availability, insurance reimbursement, and patient choice. VNA trains their home health clinicians on how to best respect the patient's choices related to PAC, including who will provide the services and which services they will receive. When a patient refuses a service, whether related to hygiene or medication, a home health clinician can use motivational interviewing techniques to identify barriers that may stand in the way of behavior modification and the patient's desired goals.

Educating the patient on the potential impact refusing a service can have on their health can help, but ultimately, the decision boils down to the patient's choice. “It's a really delicate balance that we try to bring to facilitate change when we can and to respect people and their life choices whenever it doesn't place anyone else in immediate harm, and when they are legally competent to make their choices,” said Rolfe. VNA keeps all the healthcare providers involved fully informed of their patients' decisions.

They really don't want to go to a facility in Nashville that is 80 miles from their home, friends, and people they know. They would rather go to a facility at home where they know people. The driving factor here is people's preference and comfort level more than it is their medical condition.

Vanderbilt's transition advocates remain sensitive to a patient's right to choose, especially those coming from rural areas. “They really don't want to go to a facility in Nashville that is 80 miles from their home, friends, and people they know. They would rather go to a facility at home where they know people. The driving factor here is people's preference and comfort level more than it is their medical condition,” said Schnelle. He and his colleagues recently completed a 6-year study on how health literacy affects hospital discharge and post-discharge outcomes, including patient choice. They found that the more health literate, the more involved the patient is in decision making.

In Lexington, LRHC launched the “You Have a Choice” campaign following a major decline in swing bed admissions starting in 2012. Several factors were contributing to acute care patients from other facilities being unaware of LRHC's swing bed program as a PAC option, so LRHC began to actively educate patients and the community on their rights. External mediums are used to promote the campaign, like social media, TV, radio, print ads, and this video spot:

When patients are sent to a tertiary facility for an operation, their LRHC primary care providers are intentional with reviewing the multiple local PAC choices patients have: home health, the nursing home's skilled nursing facility services, or the local therapy center. “A patient's emotional health and attitude about post-acute care is critically important; removing them from the decision seems, at best, counterproductive,” said Marsh. “If it's not our hospital, that's fine too! It's just mostly a matter of a patient understanding that they have a choice,” said Marsh.

Additional Resources

- Transitional Care Management: Care Management Reimbursement Strategies for Rural Providers, Rural Health Information Hub

- Market Characteristics Associated with Rural Hospitals' Provision of Post-Acute Care, North Carolina Rural Health Research Program, 2018

- Rural and Urban Provider Market Share of Inpatient Post-Acute Care Services Provided to Rural Medicare Beneficiaries, North Carolina Rural Health Research Program, 2018

- Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy – Chapter 7: Post-Acute Care: Increasing the Equity of Medicare's Payments Within Each Setting, MedPAC, 2018

- The Financial Importance of Medicare Post-Acute and Hospice Care to Rural Hospitals, North Carolina Rural Health Research Program, 2017