Nov 10, 2020

Nursing Preparedness: Words from Researchers and Rural Nurses

In August 2019, the University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health Rural and Minority Health Research Center published results from a national web-based survey focused around nurses' personal perception of training preparedness. Out of 435 respondents, 72 identified themselves as rural nurses, 42 working in the ambulatory setting. Of the rural respondents as a whole, approximately 11% held diploma degrees, 11% held associate degrees (ADN), 27% held bachelor's degrees (BSN), and 40% held master's degrees (MSNs). The study's raw data indicated that about 85% of rural nurses felt their training prepared them for their job, compared with around 94% of suburban and urban nurses.

As a nursing doctoral candidate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Nursing and member of the Rural Nurse Organization, Jennifer Kowalkowski is not just aware of rural nursing preparedness and results as noted by the South Carolina researchers, she is working to remedy that disparity with her research efforts. She realized this was a unique focus when she tried to find academic collaborators on her own campus — and in other areas of the U.S. — with similar research interests.

"I'm interested in creating best practices for educating undergraduate nursing students in the nuances of rural health," Kowalkowski said, "To elaborate, I'm working on educational content that promotes an understanding of what influences rural health disparities, why those influences impact rural health outcome measures, and how training registered nurses to meet the demands of caring for rural populations can help decrease those disparities. There aren't many other nursing researchers currently in this space."

Kowalkowski said her passion for the work starts with the story of her own rural roots as a member of a fourth-generation Wisconsin dairy farm family.

"I grew up wanting to be a veterinarian," she said, sharing a pivotal anecdote that happened when she was 16. "One day, a heifer went through me, not around me, and I thought, do I want to really spend my days endangering my life with taking care of animals so much bigger than me? I'm short and I'm not going to get any taller."

Leaving veterinary dreams behind, she eventually chose another caring profession: nursing. As a registered nurse (RN), she provided direct patient care in critical care units and also provided palliative care. Although she worked in urban locations, her care assignments always included rural patients. She understood the multiple factors associated with their healthcare access issues and she understood their work environments. She said as she listened to providers who'd never been in rural areas provide advice, education, and follow-up instructions — many of the elements associated with health disparities — she realized there was a major opportunity to make a difference for nursing professionals to more closely align those words with the realities of rural living.

From across the country, other registered nurses in leadership and educational positions shared their stories. Read more in Rural Registered Nurses: Stories of Caring for Their Communities.

Now in a doctoral program in order to make that difference with her research and student teaching, Kowalkowski said she is grateful for the overwhelming support of her academic advisor and other nursing school faculty members. Because of that support, she was able to engage in a 2018 quality improvement project that involved 63 nursing leadership members from a Wisconsin rural health network co-op, 15 academic faculty, and 28 nursing students. Data were collected from online surveys as well as face-to-face interviews. Elements of the research were:

- Use of the stakeholder engagement process, an evidence-based method for identifying and addressing shared priorities

- Labeling educational needs as a theory-practice gap

- Understanding faculty and co-op nursing leaders' personal rural experiences in order to influence and strengthen curriculum development

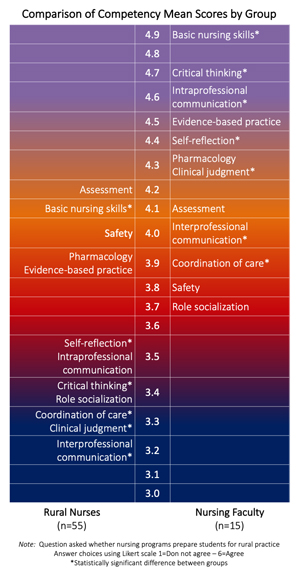

Her work, summarized in a poster presentation for the 30th International Nursing Research Congress, also included an examination of existing nursing competency standards with respect to rural practice preparedness (Figure 1). Competency standards were based on the AACN (American Association of Colleges of Nursing) Essentials, a broad literature review, and competencies suggested by rural nurse preceptors themselves. With the exception of safety and physical assessment, nursing faculty rated preparation of nursing students for rural practice higher than the rural co-op members for all competencies. A statistically significant difference was found between the ratings of nursing faculty and rural practicing nurses for seven of the 12 professional competencies. Three of those seven were critical thinking, clinical judgment, and intraprofessional communication.

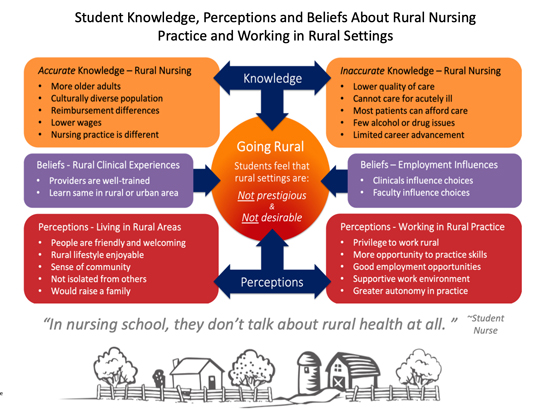

Her research also included looking at the student nurses' perceptions of rural areas in general.

"It was especially important to formally evaluate nursing students' perceptions of their training and their perceptions of rural culture," Kowalkowski pointed out. "Since I grew up as a fourth-generation Wisconsin dairy farmer and am now in the position of interacting with nursing students, being able to quantify and qualify this information becomes important for efforts focused on increasing a prepared rural nursing workforce."

For example, student nurses shared that after learning and working in rural locations, they found that a rural environment allowed a broader use of their skills, increased practice autonomy, yet support when needed, and that good employment opportunities existed in rural areas (Figure 2).

Kowalkowski said that with project completion, participants recognized its scaleability — especially important in view of regional variation across rural America. She said she was also pleased that results are being used for additional work.

"I'm finding that the results are being used to bring increased awareness of agricultural-related health and well-being in Wisconsin," she said. "They are also being used to help design policy and fund advocacy approaches to support rural nursing clinical experiences and develop nursing faculty with rural expertise. You can't have more rural nurses without having nursing faculty to educate them. It's important to not lose sight of that."

Other Wisconsin Nurses Weigh In On Preparedness

While Kowalkowski's project included nursing academics, administrators, and students, several Wisconsin direct care RNs offered their perspectives on preparedness — and staying up-to-date — while practicing as a rural registered nurse.

Lori Laluzerne grew up in a rural community located in the "thumb" of Wisconsin. She shared that her path to nursing was the result of a personal medical experience.

"I was an 8th grader and suddenly found myself to be the surprised recipient of a penicillin injection," she said. "I'm not sure what it was about that experience, but from that point forward, I knew I was going to be a nurse."

After getting her bachelor's degree in an urban Wisconsin setting, she returned home and got a job at the hospital in the community where both her and her husband's families lived. She worked on the medical-surgical unit for several years and then was encouraged to cover the emergency room — where she's now been for the last three decades. She said one of her biggest surprises about rural nursing is acuity of illness: Caring for high-acuity cases that come into a rural emergency room is an example of the need for preparedness.

It's important to understand this: Rural doesn't equate with simple.

"When I first started 30-some years ago, I thought rural care wasn't going to be as challenging compared to the complex problems that urban locations with their teaching hospitals and bigger facilities care for," she said. "But I've learned that every day here is different. Unique. Full of surprises that provide so many experiences and challenges. It's important to understand this: Rural doesn't equate with simple. The same critical things that present in urban settings come into our hospital's doors left and right."

Laluzerne shared what she believes are several of the important skills and professional attitudes also associated with rural nurse preparedness.

"Our hospital is a Critical Access Hospital and we have to be very good at physical assessment skills and our critical thinking because we are the voice of what's happening with our patients," she said. "Right along with minor cuts and bumps and bruises, we care for strokes, STEMIs [heart attacks], trauma, and sepsis patients. That means a rural nurse must have a solid foundation of knowledge and must remain engaged in continual learning, getting and updating certifications, and taking advanced classes. Medical care is ever-changing and new evidence-based practices must be used. There is no putting your head in the sand here."

Laluzerne has been recognized for her mentoring skills — another element of rural preparedness — when new nurses come on board.

"We provide a tremendous service to the nursing profession and to our community when we are mentors and resources for other nurses," she said. "Yet as a mentor, I believe it's also important to be grateful and appreciate everyone who contributes to your own personal knowledge. I've worked with RNs, paramedics, physicians, and assistants who've taught me so much over the years. I continue to learn from the new grads walking through our door.

"I believe that the most important thing about mentorship is actually providing that example of how working alongside one another provides the best outcomes for our community members who trust us with their medical needs. It is a privilege to be an RN. Bedside nursing in the ER is where my heart and passion lie. I love working with my ER team members. Having an administration who supports these values allows our ER department to deliver excellent care."

Providing Preparedness: Nursing Internship Experience

In addition to Laluzerne's perspective gained from many years of experience, another Wiconsonite, Christopher Keller, shared his path to nursing and his personal view of preparedness gained through a rural nursing internship.

Not sure of a career direction when he graduated from high school in rural Wisconsin, Keller decided to work in the heating and cooling industry along with volunteering for the local EMS, a life patterned after his father's. However, Keller said he always felt like he wanted to take care of people in a different capacity than EMS. After the first of his two children were born and with his wife's full support, Keller began his path to becoming a registered nurse while continuing to work full-time.

"In 2015, I enrolled in the community college that's about an hour away," he said. "I got my prerequisites done and in my last year of nursing school for my associate degree, I got into the nurse intern program in my hometown hospital where I was born and was hoping to eventually get a job."

Keller said he's grateful for the internship for several reasons. First, he was able to practice his new skills. Second, that practice happened under the watchful eyes of the experienced staff nurses.

"Nursing school gave me a good foundation, but what was most helpful for me was the nurse intern program," he said. "That's where I was able to learn the most. At our small hospital, I was able to use more of my skills than at the larger facilities we'd been at as student nurses. Plus, the nurses here seemed really interested in teaching me. Their experiences gave me a different way of looking at things and I've found that very helpful."

Keller now has that job in his hometown hospital and is formally assigned to the emergency room. He was quick to emphasize that rural hospital staff must be flexible, so some days he's assigned to medical/surgical units or picks up extra shifts. He shared how working on the healthcare provider side of his community has drastically changed his previous layperson perception of his hospital.

"Before I started working here, I'd heard the stories that this hospital provided a bandaid and sent patients off to get real treatment," he said. "Now I work here. Now I see the quality care we provide. Now I see the high level of care we provide. We have an operating room with staff on call 24/7. We stabilize patients with severe cardiac problems, like heart attacks that required TPA administration ["clot-busting" medication]. We get people stabilized when they're severely ill with overwhelming infections. We're a certified level-three trauma center. Our lab has blood products that we're able to administer and save people from bleeding to death. I know that if this hospital were not here, many lives in our small community would be lost. Yes, I'm a nurse at a place that's a lot more than a bandaid."

From Arizona: New Grad's View of Preparedness…and Rewards of Nursing

Though many of his experiences mirrored comments provided by the Wisconsin nurses, Ian Leodoro also shared his path to nursing and provided another perspective on preparedness.

"When I was a little kid, about seven years old, my brother and I were chasing a rabbit when it went down a big hole and we saw the hole collapse on it," Leodoro said. "We dug that rabbit out. It wasn't breathing. For whatever reason, all I could think was that I had to do chest compressions. When I did a few little ones, it spit out a bunch of dirt, woke up, and ran away. I thought to myself 'Wow! How great was that! I saved that rabbit! Maybe I should be a doctor.'"

Growing up in rural Arizona, Leodoro said his path to direct patient care bypassed medical school and instead took him to nursing school — via working in the marine industry, followed by a few years working in the operating room as a surgical technician assisting with operations. He continued working as a tech while getting a bachelor's in health science, completing his nursing prerequisites, and, finally, nursing school. Having gained his associate degree in nursing, he's worked for the past five months as an OR circulating nurse in a rural hospital.

"Though I didn't have a direct path to nursing, I always felt a constant motivation to become a nurse," he said, sharing that as the years passed, medical school was no longer an interest. "My passion is helping people get better, listening to patient concerns, understanding not just their physical concerns but their emotional concerns. As a nurse, I can do those things and really have a positive impact on someone's life."

To date, Leodoro said he's realized that one of the most important skills for rural nursing — and nursing in general — is communication with everyone on the care team and especially with patients. As he reviewed his recent training, he said there are some skills emphasized in school that he didn't truly appreciate until he put them to use.

"In a rural hospital, you don't always have a pharmacist assigned to the OR, so sometimes nurses have to mix medications," he said. "Especially in emergency situations, being able to plug in the numbers and do calculations quickly and accurately was something I was grateful that they really pushed us on in nursing school."

Because of his path through other careers before eventually becoming an RN, Leodoro said he wanted to encourage others that if they've got that dream to become a nurse to not give it up.

"I hope that anyone thinking about nursing stays persistent in going after that degree," he said. "Everybody wants a paycheck and everybody's got a family to feed, but it's a profession that offers so much more than that. We connect with people and make people better. Nothing is more rewarding."