Mar 21, 2018

What's MAT Got to Do with It? Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Rural America

Related Articles:

Understanding

the Science of Pain and Opioids

The

"M" of MAT: Medications for Opioid

Use Disorder

Rich or poor, young or old, urban or rural, highly educated or less so, from birth to last breath, a universal experience is pain. Patients and families hope – and expect – that modern medicine will relieve that experience. Opioids are often the healthcare provider's first choice for treatment.

Opioids' impact on pain varies depending on the cause of the pain. Ongoing use — coupled with genetic predisposition and vulnerable psychosocial settings — can cause what scientists now recognize as a chronic disorder of the brain: opioid use disorder, or OUD. Medication-assisted treatment, or MAT, is an effective evidence-based treatment for opioid use disorder.

Rural experts point out that even though death rates related to opioids don't exceed those related to alcohol use disorder or suicide, the great concern is due to the rate of increase in these deaths. An October 2017 CDC MMWR report provides a granular look at urban and rural opioid data. From 1999 to 2015, the study reveals a "rising death rate of drug overdoses in rural areas," finding a prevalence rate that increased 325%, contrasting with an urban increase rate of 198%. The report also highlights one likely cause of this increase is "persistent limited access to substance abuse treatment services in rural areas." The report's experts suggest two public health interventions for improving rural statistics: prevention activities, for example using opioid prescribing education for chronic pain; and creating better access to evidence-based substance abuse treatment, including medication-assisted treatment (MAT).

Rural public health providers hope increased access to MAT will have a similar positive impact on rural opioid issues that is already seen with rural prevention efforts. Larry LaCross, LMSW, CAADC, CCS, who works for Catholic Human Services, Inc. in Alpena, Michigan, confirms that the integrated approach of his organization, several local Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and local MAT providers is demonstrating success with OUD treatment.

"We treat clients with significant life struggles, and so much suffering," LaCross said. "But with MAT treatment, in 6 months, 9 months, a year's time, some of them have completely changed their lives. It's an absolutely remarkable turnaround to be a part of."

What Is Medication-Assisted Treatment?

Medication-assisted treatment, or MAT, is an evidence-based treatment for substance use disorders, including OUD. The Surgeon General's 2016 report, Facing Addiction In America, says MAT "is a highly effective treatment option for individuals with alcohol and opioid use disorders. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the efficacy of MAT at reducing illicit drug use and overdose deaths, improving retention in treatment, and reducing HIV transmission."

Methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone are the three medications used for OUD. Experts say this treatment involves partial or full blockade of problem opioid effects in the brain. Medication selection is based on the "whole-patient" approach. According to the American Society of Addiction Medicine, no matter which medication is selected, the goal is the same: getting the patient to feel normal, have little to no side effects or withdrawal symptoms, and have controlled cravings.

But MAT is not just medications. Acknowledging that MAT is often misunderstood as a medication-alone treatment for OUD, MAT prescribers point out that the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) specifically notes MAT is to be used "in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies, to provide a whole-patient approach to the treatment of substance use disorders."

MAT Alone? Exceptions

Though MAT is endorsed as part of a program using medication in addition to counseling and behavioral health interventions, situations might arise where patients will want medication, but offer resistance to the other services. MAT provider and American Society of Addiction Medicine's (ASAM) board of directors member Dr. Miriam Komaromy suggests that with extra caution, prescribers can still help that individual.

"When someone is ready to try medication-assisted treatment, but not ready to try counseling, I am willing to work with them," she said. "But, I follow them very closely. I do a lot of check-ins, focus on relapse prevention, management of inter-current issues. I don't say to them 'if you're not going to counseling, I'm not going to work with you.'"

Komaromy points out that because MAT sets someone up for becoming clear-headed, the patient will often realize they lack coping skills to deal with what often was a "part of their life masked by the substance use."

"Initially, someone may not be ready to start with counseling, but often they come to the conclusion that 'hey, I don't know how to handle my anxiety, my anger,' or they recognize they want an alternative to that powerful urge to pick up a needle to handle their stress," she said.

Komaromy points out several evidence-based studies demonstrate that with or without counseling, MAT helps patients stop or significantly decrease their drug use. She says these studies show that patients who do not engage in counseling can still experience major benefit from medication treatment, although she notes that in these studies the "no counseling" arm of the study included very close, attentive follow-up by the prescriber, which may actually have included some of the most important elements of counseling.

"In practice, what I see is the importance of having those resources available," she adds.

MAT Benefits

Like LaCross, Komaromy says she sees MAT benefits firsthand. But she says understanding benefits starts with acknowledging the contrast with "the abysmal statistics without MAT."

"Opioid use disorder kills young people," Komaromy said. "Detox alone doesn't change outcomes with its relapse rate of 80 percent, so we need to access every type of treatment modality we can to make a difference, especially since medications are shown to be profoundly effective."

Komaromy also shares there are additional benefits of MAT for patients with OUD.

"It decreases opioid craving, stops withdrawal symptoms, greatly decreases amounts of drug used, dramatically decreasing HIV and hepatitis C infections," she said. "And all that in addition to decreasing overdose death risks and mortality rates."

Who Can Prescribe MAT Medications For Rural Patients?

Rural access to MAT first starts with providers who want to help patients with OUD and are willing to complete steps involved with obtaining specific medication prescribing privileges. Methadone is prescribed through a "methadone clinic," a specialized clinic that has received special federal approval to become a regulated Opioid Treatment Program, or OTP. (Note: In contrast to being used for OUD, methadone is often used to treat problems like cancer pain. In this setting, prescribers must have a state license along with a Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) controlled substance license.)

To become a buprenorphine physician prescriber, an eight-hour training course must be completed before applying for a specialized DEA waiver, a process that usually takes 45 days. Special permission can be obtained for more immediate prescribing needs as long as the provider is licensed, has a DEA registration and has completed the training.

Due to the 2016 Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA), nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) can also become prescribers. This CARA provision was specifically designed to address MAT needs in rural and underserved areas. These providers follow the physician steps to obtain waivers, but require 24 hours of training rather than eight. In January, the DEA formalized waiver privileges for these providers. Experts say it's important to note that despite the expanded NP and PA prescribing privileges, some states do limit these providers to prescribing buprenorphine under the close supervision of a physician.

Naltrexone, a third MAT medication, can be prescribed by any licensed health provider.

MAT Is Happening In Michigan FQHCs

Many rural organizations across the country are providing MAT. With new collaborative opportunities inherent to MAT, previously siloed groups are making treatment access more seamless. With these collaborations, LaCross says their Michigan organizations are changing lives of clients and their families by the whole-patient approach that is MAT.

Previously providing the counseling portion of MAT for a few specifically referred patients, LaCross explains that his CHS team was approached by the local FQHC, Alcona Health Center, to create an integrated care program which also included the MAT providers from the community's Freedom Recovery Center.

"Alcona wanted to have an organized response to the local opioid problem," LaCross says. "Freedom Recovery had well-functioning MAT infrastructure processes. We were already doing the specialized substance abuse counseling, so the program design focused on delivering all these services collaboratively where patients were already getting their medical care: within the four walls of the FQHC."

Putting their entire program into a pie chart, LaCross indicates the medication-specific MAT activities are about 30% of the integrated approach. He shares that an unanticipated success for their program was participant enrollment issues.

"These clients have so much social vulnerability and not much stability," he said. "But the integrated care helps bridge those issues. In the end, a population who typically 'no shows' for appointments shows up. Their treatment is successful, they're back to work and with their families again."

MAT Meets Wrap-Around Services In Colorado

In rural and frontier Colorado, Southeast Health Group (SHG), a private, nonprofit corporation providing primary care and behavioral health services, is also providing integrated OUD care in six counties. SHG's Chief of Physical Health Operations Jacqueline Brown, MSN, FNP, says the group has offered injectable naltrexone for substance use disorders, but more recently identified a specific community need to expand OUD treatment. Brown shares they've worked hard to integrate with primary care and, with outside funding sources, have been able to offer other "wrap-around" services like chiropractic interventions, massage therapy, and physical therapy. Brown explains these interventions are needed for pain management since many of their patients have OUD tied to chronic pain conditions.

Using the pie chart example, Brown said that medication-specific MAT activities are about 20% of their comprehensive OUD treatment. She emphasizes their interdisciplinary teamwork is essential to creating the right plan for their OUD patients.

"Our philosophy is that MAT medications are very important, but are not a stand-alone treatment," Brown said. "You have to address their pain, and especially address the adverse life experiences that have gotten them here. Giving them [buprenorphine/naloxone] is only part of their treatment."

SHG's clients are referred by community practitioners, families, and even law enforcement agencies. But Brown says that the best testament to their program's benefits are clients who are peer-referred, hopeful that they, too, will have treatment success they've seen for others.

MAT Meets Telepsychiatry and Telebehavioral Health In North Carolina

The American Psychiatric Association's Committee on Telepsychiatry chairperson, Dr. Jay Shore, said since providing MAT medication services involve prescribing controlled substances, telepsychiatry has one significant challenge for MAT-prescribing psychiatrists: the law.

"The Ryan-Haight Act requires an in-person visit before prescribing medications like most of those used for MAT," Shore said. "Right now, what's being offered by psychiatrists through telehealth connections is education."

But MAT's counseling services can be delivered with virtual connections. Mission Health, in Asheville, North Carolina, is a hospital system that serves 18 counties (17 largely rural), five hospitals (four are Critical Access Hospitals (CAH)), and has several rural primary care clinics. In a June 2017 National Rural Health Resource Center webinar (no longer available online), the organization detailed how its telebehavioral health's "blended model" meets distance practice needs like those in CAH emergency rooms and on medical floors. Their model was adapted to now provide the clinical counseling portion of MAT treatment.

Darren Boice, LCSW and Mission Health's Director of Ambulatory Behavioral Health, points out that their large health system with rural providers has to be poised to accommodate new needs like those for MAT. If other organizations look to offer similar services, he says the whole-patient approach around such treatments in primary care should be emphasized.

"When MAT is needed in primary care, it might be important that your communities understand that treatment is in the context of comprehensive primary care, not a stand-alone service," Boice said.

MAT medications are prescribed by a small number of Mission Health's rural primary care providers committed to bridging the existing treatment gap where local opioid treatment programs don't cover their Medicaid patients. The virtual starting point for MAT integration began with North Carolina Medicaid's pre-treatment comprehensive mental health evaluation requirement, a workflow basic to Mission Health's mental health providers, but less so for their primary care providers. With a focus on care integration, both teams now work together seamlessly.

Mary Worthy, LMFT and Director of Behavioral Health Access, said she was also able to leverage schedules of their licensed mental health providers to provide counseling services via virtual connections, as well as some dedicated on-site hours.

"We realized there were going to be difficult pieces in making this happen," Worthy said. "But, there was a high level of support and cooperation. 'Yes, this is hard,' and 'yes we haven't done this before, but let's make this happen.' It's working."

Addressing MAT Controversies

Experts involved with MAT treatment are familiar with its controversies. First, concerns are raised about short- and long-term benefits. Next, naloxone, the medication which reverses an overdose by reversing the opioid effect that stops breathing, is sometimes seen as a medication that only promotes risky drug-using behaviors, allowing users' to be rescued from perceived experiments with higher and potentially more lethal doses. Another argument surrounds buprenorphine, often simply viewed as the exchange of one substance of abuse for another.

To address these concerns, MAT experts point out that in addition to multiple previous studies demonstrating positive impacts of MAT, current studies are focusing on better understanding of long-term results. Additionally, they point out that naloxone has prevented unnecessary deaths and its use hasn't increased risky behaviors; behaviors that are actually an uncontrollable choice caused by opioid brain disease. Experts also say they share that the medication portion of MAT is not a drug substitution, but a treatment that controls cravings and withdrawal symptoms, in addition to decreasing infectious disease transmission.

Lastly, rural MAT experts offer what most often provides the most convincing evidence that MAT is beneficial is the personal experience: due to the pervasiveness of opioid problems in rural areas, sooner or later a small, tight-knit rural community has an experience with an overdose or opioid-related death of a brother or sister, a nephew or niece, or friend who might be mom to three. These up-close experiences then put MAT on the table as a viable option to impact the opioid problem.

MAT's Rural Challenges: Where Are The Providers?

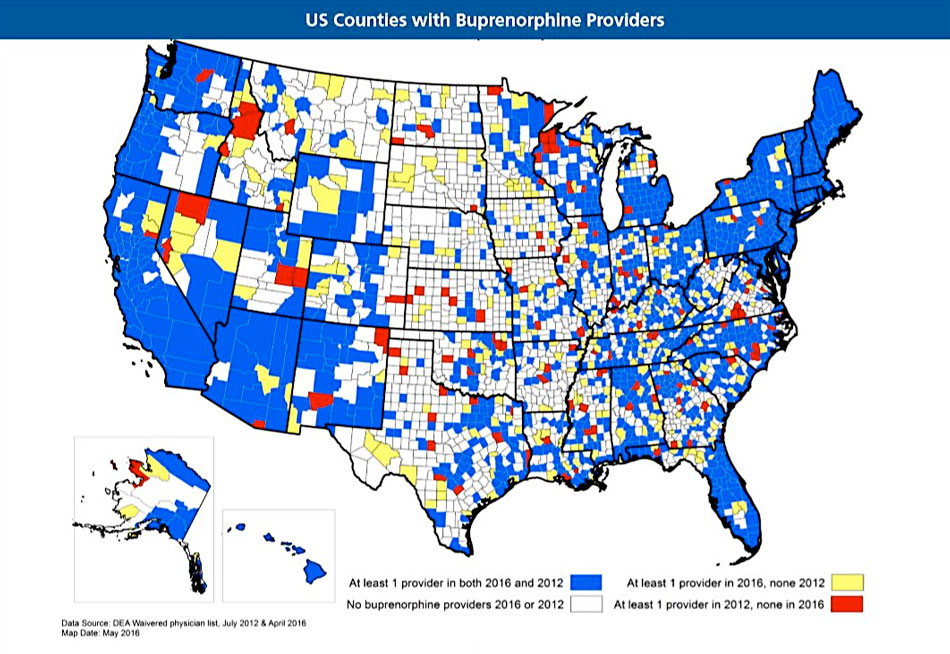

Waivered MAT prescribers don't always translate into active prescribers. SAMHSA's buprenorphine treatment practitioner locator provides waivered prescriber information. Recently, the WWAMI Rural Health Research Center reviewed changes in the numbers of these providers. The center's May 2017 policy brief notes that compared with July 2012, in April 2016 rural counties without waivered providers decreased from 1,377 to 1,188. The brief also highlights that "more than half of rural counties lacked a waivered provider."

In a separate study, the center shares three challenges described by rural prescribers: time constraints, lack of behavioral health and psychosocial support services, and concerns for drug diversion and medication misuse. A fourth challenge was inclusion of additional OUD patients into their patient roster. The researchers also note in contrast to other studies, prescribers in their study were more concerned about drug diversion issues than finances.

According to the 2016 Surgeon General's opioid report, diversion is described as a medical and legal concept involving the transfer of any legally prescribed controlled substance from the person for whom it was prescribed to another person for any illicit use. Recent journal articles, along with professional society guidelines, acknowledge that MAT benefits exceed drug diversion risks. Education regarding drug diversion is part of MAT waiver education. Federal toolkit documents (no longer available online) addressing diversion are also available.

More Rural Opioid Data

More Rural Opioid DataThe Rural Health Research Gateway, funded by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, provides additional rural opioid data in several 2017 and 2018 journal articles and policy briefs.

Other Rural Challenges: Infrastructure, Funding, Sharing Best Practices

Many experts envision the collaboration, infrastructure, and workforce needed for MAT will also serve the behavioral health needs for other rural problems, like alcohol use disorder, depression and suicide prevention. But they also acknowledge that these types of services are not the norm for most of the country and therefore even more problematic for rural areas.

Both the Michigan and Colorado groups express gratitude for federal and state public support and private funding streams allowing them to expand their services to include MAT. The Mission Health team was appreciative of a Duke Endowment grant. Other organizations across the country are able to take advantage of an increased number of recent funding opportunities; for example, states and territories that are using their SAMHSA State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis Grants. According to SAMHSA's press release, these monies – totaling almost a billion dollars – have a MAT-focus since the grants were "for increasing access to treatment, reducing unmet treatment need, and reducing opioid-related overdose deaths." Additional federal, state, local, and private funding sources are announced regularly to address the rural opioid public health emergency.

Speaking to the National Rural Health Association audience at its February Policy Institute, Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Dr. Elinore McCance-Katz, who directs SAMHSA, said that the 21st Century Cures Act included a mandate to create a behavioral health system that can work for everyone, no matter where they lived. McCance-Katz shared that the agency is transforming itself from an agency mostly providing grants to an agency that will also emphasize its technical assistance for providers.

Dr. Charles Smith, psychologist and SAMHSA's Region VIII Administrator, said McCance-Katz's transformation charge impacts his region – and likely all the others. Referring to SAMHSA's regional Addiction Technology Transfer Center Network (ATTCs), Smith says these centers are key to providing the technical assistance needed to promote innovative practices, especially those associated with MAT.

"These regional centers are especially important for rural and frontier communities' patients and families because local addiction and substance abuse experts will help disseminate and drive good clinical practices," Smith said. "When needed, they'll be able to leverage the expertise of experts outside the region."

Smith also shared that because MAT is a treatment approach based on collaboration, an important patient-centered care infrastructure is being developed in these communities bringing together prescribing providers and behavioral health professionals, including peer support specialists.

The Challenge of Parity

Smith emphasizes that OUD should be considered a chronic disease; for example, like diabetes or chronic problems resulting from spinal cord injuries. As a chronic disease, another issue surfaces for OUD and MAT treatment: parity. Parity, addressed within the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) as equal insurance coverage for mental and behavioral treatment as for other health conditions, is sometimes strategically connected to reimbursement issues that influence whether MAT is a sustainable service offered by rural provider groups.

In its November 2017 report, the President's Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis discusses this: "At this point, the largest outstanding issue is treatment limits. Patients seeking addiction treatment, including MAT, are often subjected to dangerous fail-first protocols, a limited provider network, frequent prior authorization requirements, and claim denials without a transparent process. The Commission applauds SAMHSA's work with multidisciplinary teams from states to improve parity enforcement and public education. However, we need robust enforcement of the parity law by the state and federal agencies responsible for implementing the law."

Smith said parity is equally important for patients as it is for providers and healthcare organizations.

"Parity exists to make sure we're treating OUD like any other healthcare condition," he said. "Though it has its limitations as a law, it does provide a standard by which insurance companies, state insurance commissioners, healthcare systems, and ultimately patients can feel that they have a fall-back system in order to say, 'You know what? My addiction is as important as my physical health.'"

Last Words on MAT: Patient Stories

Komaromy emphasizes that MAT outcomes are often the untold segment of the opioid story where needles hanging from arms is often the go-to visual. Komaromy, who is also involved with Project ECHO®'s opioid provider training programs (no longer available online), said missing from MAT discussions are those stories of individuals who are doing well, back with their families, back at work, and stable on medication and treatment.

"I've trained around 500 physicians at this point," she said. "I always add something that is not included in the basic curriculum: A panel of patients who share the incredibly transformative effect that MAT's brought to their lives. There's seldom a dry eye because those patients' stories are really compelling. And I always hear those patient panels are the most impactful part of the training."

General Resources

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Implementing MAT for OUD in Rural Primary Care, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (October 2017).

- American Psychiatric Association

- Michigan Supreme Court, Alpena County Circuit Courtroom: Stories Not Secrets: Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (Video, April 2016)

- The President's Commission On Combating Drug Addiction And The Opioid Crisis (November 2017)

- Rural Health Information Hub: Substance Use and Misuse in Rural Areas and Rural Prevention and Treatment of Substance Abuse Toolkit (Yearly updates)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment Improvement Protocol Tip 63

Provider Training Resources

- American Society of Addiction Medicine

- Project ECHO: Medication for Opioid Use Disorder ECHO

- Providers' Clinical Support System: PCSS-O: For Opioid Therapies and PCSS-MAT: For Medication Assisted Treatment