Apr 13, 2022

The Codes of Care: How Words and Numbers Have Transformative Power for Rural Healthcare

Two activities define the days of most rural healthcare providers. The first activity? Providing care. The second activity? Documenting the care that they provided.

Obviously, both providing and

documenting care require time. With only 24 hours in a

day, providers might find themselves short-changed on the

time for documenting their care. Experts said that,

unfortunately, this can lead to a big disconnect: To the

outside world, care that is not documented is care not

given. Taking this disconnect one step further, experts

said that this means that providers might be missing

their greatest opportunity to tell their story about just

how efficient they are at delivering quality care.

Obviously, both providing and

documenting care require time. With only 24 hours in a

day, providers might find themselves short-changed on the

time for documenting their care. Experts said that,

unfortunately, this can lead to a big disconnect: To the

outside world, care that is not documented is care not

given. Taking this disconnect one step further, experts

said that this means that providers might be missing

their greatest opportunity to tell their story about just

how efficient they are at delivering quality care.

What does that mean for rural America specifically? According to some experts, it means the successful healthcare delivery stories for this population remain either stereotyped — or simply overlooked and untold.

Medical Coding: Translating the Words of Clinical Documentation into Numbers

In order to understand how the story of rural health can be told and told well, experts said it's important to first understand the basics of medical coding. As the American Hospital Association's executive director of Coding and Classification, Nelly Leon-Chisen has had multiple opportunities to explain the medical coding process that translates providers' clinical documentation words into the numbers that tell the more complete story of health and healthcare delivery.

“Medical coding allows a way for physicians, hospitals, and any other providers to describe their patient care as a standardized number,” she said. “When medical conditions and treatment procedures become numbers, the numbers can then tell stories — almost like reading a book. After being aggregated and analyzed, these numerical codes reveal what's happening with the health and well-being of people living in a certain district at a certain time across our country. Because the numbers are internationally standardized, healthcare in our country can also be compared to countries across the globe.”

More on Medical Codes

Scientists have always liked organized systems, so it's no surprise that systematic classification of a list of human disease began as early as the 1700s. Professionals across Europe engaged in repetitive reviews and regular expansion of this list. According to a federal agency's historical report, the American Public Health Association representatives first participated in these activities in the late 1890s. Several name changes occurred over the centuries and the list eventually became an internationally utilized, standardized numerical classification system, referred to as the International Classification of Diseases, now in its eleventh revision only just completed in January 2022 — known as ICD-11 for short.

Currently, the U.S. uses ICD-10, having moved to that revision October 1, 2015, after more than 35 years of using ICD-9. While ICD-9 was mostly numeric codes, diagnosis coding under ICD-10 changed to alphanumeric codes and added almost 5 times as many disease codes. (Officially, the U.S. uses ICD-10-CM: CM for clinical modification, but ICD-10 for common usage.)

Obviously, the transition to ICD-10 required a major integrated effort among providers and all medical payers, software vendors, clearinghouses, and third-party billing services. Experts and researchers said the change allowed the U.S. to better compare its population health on a global basis. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), this change also supported:

- Advancement of public health research, public health surveillance, and emergency response through detection of disease outbreaks and adverse drug events

- Improvement of coordination of patient care across providers over time

- Enhancement of fraud detection efforts

- Better understanding innovative payment models that drive quality of care

Medical Coding's Impact on Quality of Care

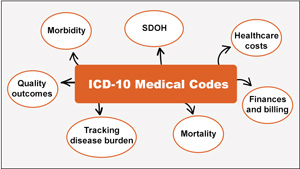

Leon-Chisen further explained that although coding is inextricably linked with healthcare billing and finances, it's important to never lose sight of the fact that it allows medical diagnoses and procedure codes to eventually become data and information that provide insight into community and population health as well as representing quality of care.

Robyn Carlson, a quality reporting specialist at Stratis Health, has spent over two decades “mining” medical records for information linked to activities ranging from workflow process evaluation to quality measure evaluation. Carlson works with the Stratis technical assistance team for MBQIP, the federally funded Medicare Beneficiary Quality Improvement Program for Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) that want to participate in quality reporting, though this reporting is currently not a CMS-mandated activity for this hospital designation. She shared what she referred to as a somewhat exaggerated example of how coding can impact quality measurement.

“Let's say a patient has chest pain, lab results, and an EKG finding that is commonly found in patients with heart attacks, referred to as ST-elevation myocardial infarction,” Carlson said. “Within the available provider documentation, the EKG finding and the blood work ends up as a case coded as a heart attack. However, let's say this lab result and EKG finding were for a patient with chest pain that was actually from trauma to the chest. When the case is reviewed for compliance with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) quality measures, quality measures were not met because the patient's problem was trauma and not an actual heart attack. The care was actually appropriate for a patient with chest trauma, but because the case was coded as an acute myocardial infarction, care did not align with the AMI measures.”

In addition to pointing out how this example highlighted medical coding workflow as a process that depends on communication between the provider of record and the coding professional, Carlson also explained how this type of quality measure coding problem is uncovered.

Coding really matters, especially for telling the story of quality. People are really looking at the relationship of medical coding and quality so much more now.

“Usually, coding problems come to the attention of the professional assigned to the quality department in a small rural hospital by way of the organization's CEO who might say, 'I'm concerned because our heart attack quality ranking has gone down. Can you tell me why?'” Carlson shared. “These quality rankings really make a difference even to a rural hospital, especially since rural hospitals have a smaller number of cases to start with. Coding really matters, especially for telling the story of quality. People are really looking at the relationship of medical coding and quality so much more now.”

Coding of Care: How Provider Documentation Is Translated into a Story Told with Numbers

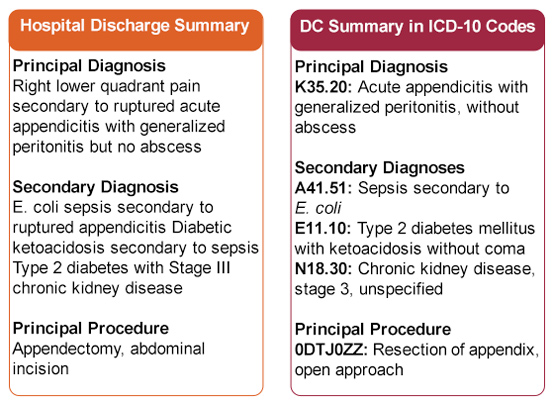

Coding of a provider's documentation is done according to strict medical coding rules. Though a medical chart review includes much of the entire record, for the majority of codes, the only information translatable into a number is information that is recorded by a clinical provider. If a provider has documented a high pulse rate, a fever, and a high white blood cell count and ordered IV antibiotics, a medical coder cannot assume that sepsis, a bacterial infection that has entered into the bloodstream and is coursing through the body, is the medical condition being treated unless the provider has clearly documented “sepsis.” Even if another member of the clinical care team — for example, a nurse — has clearly documented this diagnosis, the condition can't be coded.

How is this chart information addressed by a coding professional? It would be easy if the coder could simply pick up the phone or send an informal email and ask, “Remember patient X? Were you treating possible Pseudomonas sepsis?” Coding experts said those aren't allowable channels of clarification. There are strict rules for the official clarification process called a query. Even the language of an official clarification query has guidelines stating that the query content must be nonleading. For example, this message might be used: “What condition is being treated with the IV antibiotics?”

Experts pointed out that although this purist approach is absolutely necessary — because coding professionals are not clinicians and are not mind-readers — the extra effort of an official query process for both the coder and the clinician presents a challenge to comprehensive coding needed to tell the story of rural healthcare.

Researchers Speak Out: Coding and Its Influences on Public Health Research

In a 2020 paper comparing coding practices' impact on mortality in CAHs and non-CAHs, researchers noted that coding seemed to be a higher priority in non-CAHs and that non-CAHs capture more diagnoses, likely reflecting more complete coding, which in turn is due to more detailed provider documentation. Experts said this is likely because non-CAHs usually have large teams dedicated to both the documentation and coding processes, since Medicare payments and public report card measures for non-CAHs are based on the codes that are used.

Cyrus Kosar, PhD, is the lead author of the paper and an assistant professor and researcher at Brown University School of Public Health. After completing the study's analysis, he said he found himself stepping back and coming to the conclusion that although this research indicates that there might likely be an under-coding issue in rural CAHs, he believed that an important takeaway from the study was summarized in this statement in the paper: “The underlying issue is that claims diagnoses are primarily recorded for billing purposes, not for measuring health status or illness severity.”

“As researchers, we always need to be cognizant that the unobserved health status is a really important data element not always captured by coding,” he said. “Eventually that limitation makes its way into data sets and really can contaminate a lot of our research,” he said.

Alana Knudson, PhD, a rural public health researcher and director of the NORC Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis, has long been the research voice guiding a variety of audiences through the many rural nuances of coding and health data sets. Also acknowledging that coded data sometimes is more reflective of its link to financial impacts, she said coded data is still a valuable mainstay for public health researchers. She expressed her optimism that the new ICD-10 codes can support more robust rural-to-rural comparisons than ICD-9 codes.

“Rural America is not a homogenous environment,” Knudson said. “There are issues that affect rural communities differently. I believe that the specificity and granularity offered by the change to ICD-10 coding can help us move away from rural-urban comparisons and begin to help us better understand the differences between small rural and large rural communities and their healthcare experiences and needs. It can also be used for epidemiological research to help us better understand the severity of illnesses and comorbidities that differ by regions: for example, the rural Pacific Northwest versus the rural Southeast or the rural Great Plains. I'm confident that we'll have better information to guide decisions on how to best target interventions, adjust processes, and make organizational and culture changes that improve health outcomes. These data also help public health researchers track progress toward advancing health equity in rural America.”

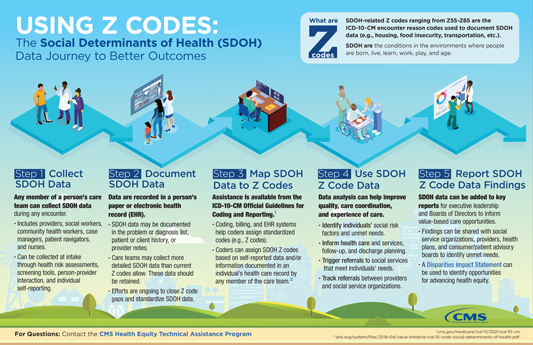

ICD-10 Z Codes: Capturing Social Determinants of Health

Knudson also suggested that the new Z codes that came with ICD-10 implementation will also bring new insight into the rural impact of the social determinants of health (SDOH), a very important aspect of health and well-being. AHA's Leon-Chisen provided additional information about these unique codes.

Leon-Chisen explained that Z codes are codes that officially depict “factors influencing health status and contact with health services.” She said that within that large code set is a specific subset of codes that describe the SDOHs, the “conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life,” as defined by the WHO.

“Clinicians intuitively have known that there are many social issues that impact health outcomes, but it's been difficult to show how this is happening,” she said. “The idea is that the Z codes that are associated with social determinants of health can allow the use of administrative data that are often part of an official medical record and found in a healthcare organization's admission screening tools.”

She said examples of these Z code categories — some listed on the AHA's SDOH Z code fact sheet — include problems related to education and literacy, economic circumstances, upbringing, and psychosocial circumstances. In particular, she's found the Z codes for housing issues illustrative of Z code benefits.

“Homelessness is a good example of the granular value of Z codes,” Leon-Chisen said. “What does homelessness mean? Are you talking about someone living under a bridge or are you talking about someone who's going from couch to couch, known as couch surfing? Or are they living in a shelter? Technically, there's a roof over their head, but the Z codes for those situations are different from someone who's actually living on the streets. That's very valuable information.”

She emphasized that Z codes are also an example of coding elements that are unrelated to reimbursement.

“Currently, there is no direct financial incentive to collect Z code-related information,” she said. “This also means there is low reporting of the codes. Yet, reflecting that there is more and more interest in these codes is the fact that there are an increasing number of proposals for adding even more codes to be able to provide increased granularity. Z codes have the potential to be really helpful in understanding the health and well-being of communities.”

Redux on Coding of Care: Z Codes Differ

Leon-Chisen pointed out that the coding rules around Z codes — in contrast to other medical coding rules — allow coders to capture SDOH information if the documentation is done by anyone allowed to document in an official medical record. This includes documentation of nonphysician providers such as social workers, community health workers, case managers, nurses, or other providers.

Coding Issues Specific to Rural Healthcare Settings

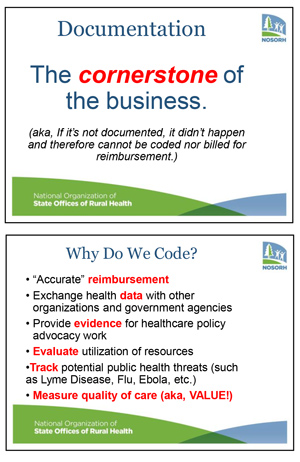

Experts have pointed out that most rural and urban clinical providers are either unaware — or just lose sight of the fact — that their medical record notes go through the coding process that actually puts data into hands of not just payers or their employers, but many other keepers of healthcare-related data sets. Some providers additionally have a low awareness that these data sets tabulate provider-specific data that reflect an individual provider's resource utilization, quality of care, and health outcome patterns. These same databases also uncover fraud, waste, and abuse.

Patty Harper, a rural coding and health technology expert, talked about the awareness around documentation and the coding work that many rural providers do themselves.

“Clinicians will say that they feel like their good work — and their hard work — is done during the delivery of care in that actual patient visit, not during the documentation of the visit,” Harper said. “It's been estimated that about 80% of rural providers in ambulatory settings are assigning their own medical codes because it's the only option they have to close an episode of care and submit a claim. Because many of these providers have never been familiarized with the impact of medical coding based on their documentation, they are unaware of the larger concepts around the fact that coded data from their work actually goes someplace else other than the payer. This includes even some providers who belong to ACOs [Accountable Care Organizations] who hold the understanding that the payment structure results from doing high-quality patient care, rather than the documentation of that care.”

Harper also said that providers' coding efforts are sometimes limited to choosing from the most common diagnoses particular to a given practice setting and listed either on a paper superbill or on a limited drop-down menu in an electronic system with a documentation-linked coding application. She added that for many small rural healthcare organizations, one element that impacts coding is the prohibitive costs of more sophisticated electronic health record programs.

Joining Harper in sharing root causes of common rural medical coding needs, Tammy Norville, a coding expert and technical assistance director for the National Organization of State Offices of Rural Health (NOSORH), said that when their member needs assessment are completed, year after year — and without failure — the “documentation, coding, and billing” category is always in the top three requests.

“Clinical documentation and coding issues, along with their impact on financial and quality results, is definitely one of the most — if not the most— worrisome and angst-causing topics that folks working in rural primary care clinics and hospitals face,” Norville said, sharing that in 2021 she did at least 26 presentations on this topic. “Despite the fact that outpatient and inpatient setting needs differ from each other, the concerns and needs are equal.”

Norville said that a common theme emerging from her presentations is that audiences often start with a common misperception that coding doesn't really matter.

“Coding really does matter,” she said. “And it's amazing when that concept begins to resonate with the audiences as they learn how clinical documentation and coding allows them to really be able to tell the story of how they deliver patient care.”

With the number of presentations she's done in the past four years, Norville said she's also discovered that, no matter the rural organizational structure, there is a universal gap in understanding that documentation and coding extends way beyond just the immediate story of an organization's reimbursement and finances, though that is important.

Both Harper and Norville pointed out another universal theme: Because the vast majority of clinical providers are trained in urban settings, urban and rural clinicians are similar in their level of awareness regarding the story they can tell with their clinical documentation.

Clinical providers need to become aware of the relationship between what they're writing and what can be coded.

“Clinical providers need to become aware of the relationship between what they're writing and what can be coded,” Norville said. “And I've found once those providers are given that information…well, once they get it, they get it! Once they get to the point where the clinical language required for coding starts to click, you have success. And if you educate at the PGY1 [post-graduate year 1] level, by the time they're PGY3s, they've mastered much of the documentation needs and are working with PGY1s and PGY2s who are also getting the education. Think about it: You could have successive graduating medical providers that actually understand how coding matters for telling the story of their patient care.”

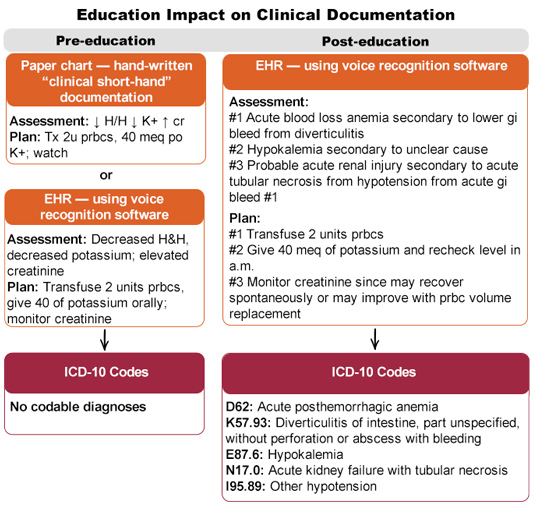

A Miniscule Amount of Time: Teaching Medical Learners Coding Concepts

Nationwide there are many examples of graduate medical education efforts around clinical documentation/medical coding education, some of which are linked only to the finances of the healthcare setting itself. Health information experts pointed out the potential benefits of standardizing this education: As little as 16 hours — or around 0.2% of total education time for a 3-year primary care-focused residency — has the potential to transform the clinical and non-financial stories of healthcare. What is that basic education? Not to teach learners to be coders, but teaching learners — including physician assistants and nurse practitioners — why codable clinical documentation matters.

Increased Coding Awareness Impacts Rural Healthcare Quality and Value

With the power of the non-financial stories that coded data can help tell, Harper explained that she worries about a consequence that might emerge due to clinical provider awareness gaps — especially for rural providers.

We need to be able to use that information to plant our flag and say, 'We are rural safety net providers and we do great patient care.'

“Rural safety net providers have got to be able to demonstrate the breadth of services that they're providing,” she said. “Without reporting them accurately with correct documentation and correct codes, nobody knows if they are truly having the impact on their communities that we know they are having. In order to still remain in a position where we should be able to benefit from cost-based reimbursement or other incentives for rural providers, if we're not telling our story in the way that others understand best — and that is by translating excellent clinical care into accurate alphanumerical data — we're not going to be able to demonstrate the really great job we're doing. We need to be able to use that information to plant our flag and say, 'We are rural safety net providers and we do great patient care.'”