Oct 18, 2023

Programs and Training Strive to Improve Care for Rural LGBTQ+ Patients

by Allee Mead

Carrie Henning-Smith, PhD, MPH, MSW, is the Deputy Director of the University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center (RHRC). She and her colleagues have been studying the behavioral and physical health outcomes of LGBTQ+ people living in rural areas.

“In the work that we did, we found, not surprisingly, that some of the poorest health outcomes and greatest barriers to healthcare access existed at the intersection between living in a rural area and being part of the LGBTQ+ community,” Henning-Smith said.

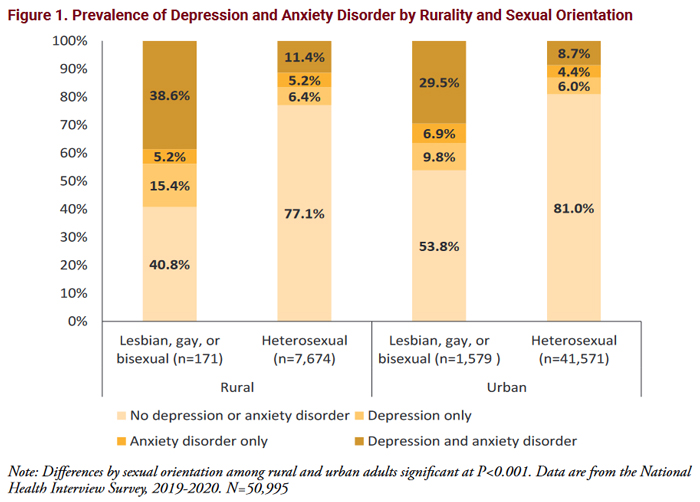

A June 2022 policy brief on chronic conditions found that rural lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults were more likely to report having three or more chronic conditions, including high rates of asthma, anxiety, and depression. A June 2022 policy brief on mental health found that rural lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults had higher rates of depression and anxiety compared to their urban and their heterosexual counterparts.

In a September 2022 policy brief, the University of Minnesota RHRC interviewed 14 national LGBTQ+ organizations. These informants shared that the two most common challenges for rural LGBTQ+ people were a lack of resources and understanding among healthcare staff. There were also concerns around stigma and fear of — or past experiences with — discrimination. Discrimination can happen in communities of any size, but rural residents who experience discrimination tend to have fewer alternatives for care.

Mariana Tuttle, MPH, is a research fellow at the University of Minnesota RHRC. She explained that there is a “mental burden” that comes with LGBTQ+ people not knowing if the healthcare staff might be unwelcoming or simply uneducated about LGBTQ+ care. “Not everyone may be hostile, but they may just not have any idea of 'How do I interact with this person? Or what do they need? Or what does that identity actually mean?'” Tuttle said.

Another concern is privacy, as Beth O'Connor, Executive Director of the Virginia Rural Health Association, explained: “In rural communities, HIPAA only does so much when your doctor is also your neighbor or your aunt or your Sunday school teacher or — let's face it — your neighbor who is also your aunt who is also your Sunday school teacher. And what does that mean to be out in a rural community and receiving healthcare?”

Tuttle added that another “piece of exacerbating mental health challenges for LGBTQ+ folks in rural communities” is a sense of loneliness. While isolation may be a concern for rural residents in general, LGBTQ+ people may not know of any other individuals in town who share their identity. “Even if they've got a pretty accepting community, it can be pretty isolating and lonely to not know any other gay or bisexual or transgender people nearby,” Tuttle said.

“I think a lot of urban folks would say, 'Well, just move to the city if you're alone there,' but that rurality piece is a huge part of your identity too,” Tuttle said. “And a lot of people don't want to move. They want to live in their homes. They just want to do that with resources or access to care and with other friends.”

To receive good healthcare and have good health outcomes, it's important to have a provider who knows and understands you and your lived experience.

Henning-Smith said, “To receive good healthcare and have good health outcomes, it's important to have a provider who knows and understands you and your lived experience.” But rural areas have fewer providers in general, much less providers trained in LGBTQ+ care, so “that might mean that people are going without the really essential and life-saving care that they need,” she added.

Awareness and Training Programs

O'Connor is part of the Pride of Rural Virginia program, which started when the Virginia Rural Health Association hosted a board retreat in 2018 and posed the questions: “Who are we not serving? Whose voice is not at the table?” O'Connor said. “One of the answers we came up with was the LGBTQ population in our rural communities and the need for them to be able to access healthcare in an equitable manner.” According to a 2021 Pride of Rural Virginia presentation, about 426,000 Virginians are LGBTQ+, and 22% of them — 93,720 — live in rural communities.

Pride of Rural Virginia provides training and resources to healthcare staff on ways to provide LGBTQ+ care and make their healthcare facilities more welcoming and affirming. This program also hosted “Community Conversations” in rural communities to bring together providers, LGBTQ+ folks, and allies to discuss healthcare access.

J Gallienne manages a gender-affirming healthcare program at multiple clinics in Virginia. For Pride of Rural Virginia, Gallienne and their co-facilitators Melissa-Irene Jackson and Afton Bradley create, implement, and facilitate LGBTQ+ affirmative training for healthcare and mental health providers. “We have extensive history in training and offering technical assistance to service providers on LGBTQ healthcare with a focus on trans healthcare and equity,” they said.

Pride of Rural Virginia training covers topics like LGBTQ+ definitions and terminology, trauma-informed care, historical treatment of LGBTQ+ patients, and current challenges facing LGBTQ+ people. The training also shows providers how to collect patient information regarding gender identity and sexual orientation and how to make a healthcare facility and patient registration process more welcoming. Ongoing technical assistance is also available for participants. Bradley, a family nurse practitioner, discusses medical care and considerations for LGBTQ+ patients.

Camille Evans, LCSW, Director of Behavioral Health at Valor Health, a Critical Access Hospital in rural Emmett, Idaho, is part of Pride in Idaho Care Neighborhoods (PiICN). PiICN began after she discussed with Rachel Blanton, Chief Operating Officer of nonprofit Cornerstone Whole Healthcare Organization (C-WHO), and others different ways to improve their LGBTQ+ patients' care.

PiICN connects C-WHO, Valor Health, a statewide medical residency program, and other regional entities. It provides training, resources, and virtual consultations to rural providers in Idaho working with LGBTQ+ patients.

Evans said, “A focus of mine has been expanding care and creating a safe environment for the LGBTQ population. That's something I've been working on quite a bit over the last three to four years.” As a parent, Evans has made her home a safe space for LGBTQ+ kids, both her own and friends. She wanted healthcare to be a similar space.

When Evans first started talking to local physicians about LGBTQ+ inclusive care, some of them told her that this type of care didn't apply to them because they didn't have any LGBTQ+ patients. “My argument was, 'You are not creating a safe space and you're not asking the right questions,'” she said. Once providers started doing this, they found that they did have LGBTQ+ patients, Evans said.

So we said, okay, we need to run this through the filter of the experience of rural healthcare.

Blanton and her C-WHO team looked for checklists, toolkits, or roadmaps to improve their care but found they were written for urban healthcare facilities. “They're not for Critical Access Hospitals. They're not for rural primary care provider offices,” Blanton said. “So we said, okay, we need to run this through the filter of the experience of rural healthcare.”

At the local level, Blanton's team talked to patients and providers who identified as LGBTQ+ or were allies. Then they worked with existing state networks for integrated behavioral health and rural primary care to find providers with a teaching background and expertise in providing hormone therapy and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), medication to prevent HIV infection.

After finding experts, the PiICN team developed a consultation model so that primary care providers at Valor Health could receive guidance in providing hormone therapy and PrEP to their patients without referring them outside their rural community. The PiICN team also connected with urban programs for more regional support.

“At the local, state, and regional level, we had different strategies [of building partnerships], but it all comes down to building those relationships of trust,” Blanton said.

Ways to Improve Care for LGBTQ+ Patients

Henning-Smith in Minnesota said an important first step to improving care for LGBTQ+ patients is to “assume that you have LGBTQ+ patients in your healthcare facility.” She said, “I have heard people say, 'Oh, no, we don't have anyone like that here in this community.' That's just simply not true.”

Start with the folks who are experiencing the disparities and ask them what support they need.

O'Connor in Virginia recommended starting with local pride organizations: “People tend to think, 'Oh, this is a healthcare issue. I'm going to start with healthcare providers.' Start with the folks who are experiencing the disparities and ask them what support they need.”

Henning-Smith also advised learning what community-based resources are available, including libraries, schools, and senior centers. She then recommended “doing everything you can to educate yourself,” whether that's attending webinars and trainings or reading books.

Henning-Smith said it's important for all staff members, not just providers, to receive training: “Everyone in that setting needs to be on board to ensure that it's a welcoming and inclusive place because it only takes one person to misgender someone…or say something harmful or hurtful for that place to not feel safe and not feel welcoming and inclusive.”

The Pride in Idaho Care Neighborhoods Roadmap: A Guide For Healthcare Communities provides tips on creating and developing a similar program. Some advice includes:

- Train all staff members — not just doctors — on inclusive care and respectful language so that patients feel safe from the moment they walk into the facility.

- Build relationships with providers outside your facility in case you need a consultation or refer a patient with more complex health needs.

The LGBTQ Primary Care Toolkit offers some rural-specific information as well as ways to use more gender-neutral language on patient forms and during exams.

Tuttle in Minnesota said that having a rainbow flag or pin can quickly put an LGBTQ+ patient at ease. Blanton in Idaho suggested that healthcare staff adjust their medical records so that all patients can list their preferred name and pronouns. Staff can also list their pronouns on their name badges or announce their pronouns when they meet with patients.

Evans in Idaho said, “With Cornerstone, what we are working on is just really helping other clinics to be able to start providing more inclusive care and making small changes like adding sexual orientation and gender identity to their intake forms and making sure that the electronic medical record has a way of identifying [LGBTQ+ patients].”

O'Connor in Virginia also advised that healthcare providers learn what they can before they meet with a patient and avoid blanket statements like, “Oh, well, this is new for me. Let's learn together.” She said, “That is not reassuring for the patient. I would very much encourage people to be proactive and learn what you can before you get a patient in your waiting room that identifies as LGBTQ+. You certainly wouldn't want to have your doctor say, 'Oh, well, I've never treated breast cancer before. Let's learn together.'”

Blanton stressed that the goal is for providers to gain enough knowledge and understanding so that patients will “feel comfortable coming back to you and seeking care, because right now the data shows us that a lot of those patients don't.”

But she added that it's okay for providers to ask what a particular identity means to an individual patient and what kind of care they are looking for. For example, some patients who are asexual — people who do not experience sexual attraction — have never been sexually active, while other asexual patients have.

“Having some humility about what you do and you don't know about a person is really important,” Blanton said.

“We know that rural healthcare providers have so much on their plate,” Henning-Smith in Minnesota said. “It's a lot to ask that they be well-versed in every population and in every issue. But the lack of understanding or lack of training…means that it can be much harder for people who live in rural areas and are LGBTQ+ to find providers or healthcare settings that feel welcoming and comfortable and affirming.”

Positive Feedback

So far, PiICN in Idaho has trained 52 healthcare staff — completing a total of 700 hours of training — and has directly served 104 patients. PiICN has been invited to provide a rural perspective on different national panels and organizations. “We're excited that rural now has a voice in LGBTQ+ care at the national level,” Blanton said.

Blanton also said that healthcare students, especially leadership groups, “are reaching out to us to do more presentations and to do more patient panels and to get on the curriculum for certain education activities.”

Evans remembered an LGBTQ+ patient who had anxiety and difficulty in regulating emotions. Through therapy and LGBTQ+-specific care, this patient is doing much better.

In Virginia, over 50 healthcare staff from three Rural Health Clinics have completed the Pride of Rural Virginia training. This fall, the program will provide in-person and virtual training to over 600 employees at a large healthcare facility.

“We have been very successful and have received positive feedback from providers on our training,” Gallienne said. Pre- and post-training surveys show that providers who complete the training feel better prepared to serve LGBTQ+ patients.

Participants have also shared with us how important this training was for them.

“Participants have also shared with us how important this training was for them and were glad we offered the training,” Gallienne added. “They also felt like we are approachable trainers and engage in the content in an accessible way.”

Lessons Learned

Evans in Idaho explained that there are changes rural healthcare facilities can make right away and other changes that might take time. For example, many LGBTQ+ inclusive care checklists made for urban facilities suggest having LGBTQ+ patients on the facility's board. “When you're in a small community and the LGBTQ+ population just doesn't really feel safe and they're invisible, that's probably not something that's going to happen right away,” she said.

“Strong leadership support is crucial,” Evans added. In cases of community pushback or provider hesitation, she added, “Do what you can. It gets frustrating that there's things that you want to do that the organization's not ready for, but we have to find the areas where we can start slowly turning that ship and know that it's going to be a process.”

But change is possible. “I've seen such a shift in just so much more openness to talk about that part of who some of our patients are and how they identify and what their needs might be,” Evans said. “I've got a couple of physicians that are really engaged.”

Evans added that it's important to “build a support system for yourself, especially in a rural community. What I have found is that it can be pretty isolating, because there tends to not be a whole lot of other people.” Connecting to other organizations helps reduce the isolation and helps providers and patients find needed resources.

“There are a lot of really wonderful and thoughtful providers out there who are doing amazing work in this area,” Henning-Smith said.