Nov 30, 2016

Freestanding Emergency Departments: An Alternative Model for Rural Communities

by Jenn Lukens

It was 2015 when St. Mary's Hospital of Streator, Illinois, announced its plans to close. The closure would soon leave the community's 13,700 residents with a 16-mile drive to receive emergency care. St. Mary's is just one of the 78 rural hospitals that have shut down across the U.S. since 2010.

OSF HealthCare of Peoria took an interest in the town's plight — soon the idea to introduce a different model started to take shape. An appeal was made to the Illinois General Assembly for an exception to the state law prohibiting the establishment of freestanding emergency department (FSED) in rural areas. Because of the town's dire circumstances, their request was granted. In August of 2016, the OSF Center for Health – Streator became the state's first rural FSED.

What is a Freestanding Emergency Department?

First conceptualized in the 1970s as a solution for rural communities, freestanding emergency departments have recently been getting another look from providers and policymakers. The FSED is just one of several models that are being considered as sustainable options for rural communities that can no longer support inpatient facilities. As of December 2015, 32 states have a collective total of 400 FSEDs, with just a handful of them located in rural areas.

It's like taking a saw and cutting the emergency department out of the hospital and moving it while still retaining all of the emergency care expertise and services.

According to the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), an FSED is a “facility that is structurally separate and distinct from a hospital and provides emergency care.” The ACEP recommends that FSEDs remain open 24/7 and include an emergency department, imaging, and on-site lab. David Ernst, MD, is an ACEP fellow with over 16 years of emergency medical experience in Ohio. An advocate for the FSED model, Ernst explained its structure this way: “It's like taking a saw and cutting the emergency department out of the hospital and moving it while still retaining all of the emergency care expertise and services.”

An FSED differs from a hospital in that it does not have operating or inpatient rooms, meaning patients who need that level of care are transported to a hospital. Ken Beutke is President of OSF Saint Elizabeth Medical Center, the inpatient hospital that receives patients from OSF Center for Health – Streator on a regular basis. While some Streator residents don't like the idea of being transferred for inpatient stays, he points out a big advantage of their FSED is the access Streator residents now have to the 1,000 primary care, specialist physicians, and advanced practice providers within the OSF HealthCare system.

As residents experience this new model, it is our hope that they will not only appreciate its sustainability, but also that it puts patients first.

“We are transforming healthcare and proactively addressing determinants of a healthy community through our work in Streator…As residents experience this new model, it is our hope that they will not only appreciate its sustainability, but also that it puts patients first,” said Beutke.

Two Distinct Versions

When discussing FSEDs and their financial viability for rural areas, it is important to make the distinction between two different versions of the model: independent freestanding emergency centers (IFECs) and hospital-based off-campus emergency departments (OCEDs). The majority of FSEDs are OCEDs while about 37% are IFECs and are independently run by a group or partnership not affiliated with a hospital system.

An FSED that operates under an affiliate hospital is subject to the same CMS rules and regulations that also make them eligible to receive reimbursements for the facility fees, physician fees, and office visits. Because IFECs operate independently from hospital licensure, they are not eligible to receive Medicare reimbursements for the facility fees, making the model more difficult to sustain in rural areas with large Medicare and Medicaid populations.

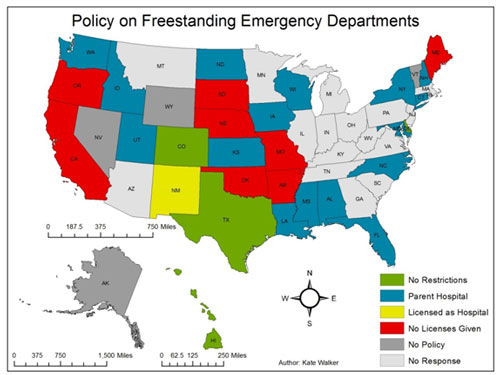

While Medicare reimbursements are regulated at the federal level, FSED licensure and requirements are regulated at the state level. As shown in the map below, only Texas, Colorado, Rhode Island, and Delaware (green states) have specific legislation allowing licensure for the construction of IFECs. Other states only allow OCEDs (blue states) while the rest do not yet have any legislation in place (grey states).

Ernst outlines some advantages of the IEFC model, “When you convert to an FSED, if it is independently owned, the level of sophistication related to doing that creates a far more efficient, far more economically-streamlined service product.” He points out that they are currently free from many federal requirements that are expected of OCED facilities to comply with Medicare mandates. This model tends to thrive in urban and suburban areas where residents have higher incomes and private pay insurances.

Based on his own experience, Beutke of OSF HealthCare makes the case for OCEDs. “When we manage our costs, being a part of the healthcare system that is able to leverage purchasing power is helpful. The way we are structured as a staff allows us to do more sharing of human resources between affiliated emergency centers,” he said. “[Becoming financially viable] will be a challenge, but a challenge that we can work with and continue monitoring as a healthcare system to make this viable for our community.”

Sarah Young, Flex Program Coordinator for the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, says that the benefits and disadvantages of each FSED model are still being explored. “I don't necessarily think there's a clear answer yet,” she said. “From a clinical practice and care delivery perspective, it can be easier for these facilities to operate if they are connected to a bigger system – for example sharing staff, expertise, or purchasing supplies. But, in theory, certainly the benefits of independent rural freestanding EDs is that they can be more responsive to their community and directly tailor services to meet their needs.”

Evaluating Financial Viability

According to Priya Bathija, Senior Associate Director for Policy Development for the American Hospital Association, financial viability of FSEDs depends on the community. “Our task force has discovered that different communities have really different situations.” She mentioned if FSEDs can find additional financial support like grants, taxes, or the creation of other services, they could have more opportunity to succeed.

George Pink, one of the authors of the brief, “Estimated Costs of Rural Freestanding Emergency Departments” and creator of the Freestanding Emergency Department Financial Assessment Strategic Tool (FED FAST), points out that the rural locations for FSEDs add challenges such as staffing, higher fixed costs per patient, and longer transfer times. Current reimbursement methods don't adequately compensate for these characteristics.

For Verde Valley Medical Center (VVMC): Sedona Campus, it was the community that helped them achieve financial viability seven years after being established by the Northern Arizona Healthcare (NAH) system. The tourist town of 10,000 raised $4 million for the construction of the building in 1995. The campus now offers a multitude of outpatient services, including primary care, cardiology, orthopedics, a laboratory draw site, imaging services, and a cancer center.

In VVMC's case, much of their overhead costs are covered by these additional services. The FSED also has a helicopter landing area designated for the safe transport of patients with critical needs to the nearest NAH hospital within 14 minutes. It's these types of services plus the collaborative efforts with the NAH system that makes the FSED model succeed for their rural community.

It works very well to serve the community and the purpose for which it was created.

“It works very well to serve the community and the purpose for which it was created,” said Randy Loveless, Director of Emergency Services at VVMC and the Sedona Campus.

Additional strategies for FSEDs to be financially viable include staffing with nurse practitioners and physician assistants instead of physicians, functioning as a satellite center, and utilizing telemedicine. Another is to offer additional community services within the structure. Although its' still new, the OSF team has created their facility as home to a one-stop shop model, offering not only healthcare, but also social and economic services to the Streator population. Their “healthy village” provides convenience for the residents and an added source of income for OSF Center for Health – Streator.

“We really believe that taking it to the next level and improving access to some of these agencies that help the social determinants of patients' needs will enhance the patient experience and outcomes,” explained Beutke.

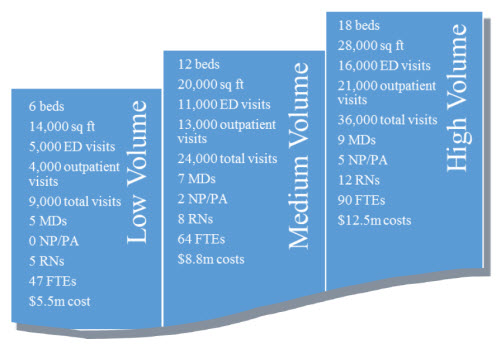

Another key to setting up a successful FSED is designing its services to match the patient needs and numbers. Below is a chart, developed by Pink and his team at the North Carolina Rural Health Research Program, which breaks down the costs of running an FSED based on patient volume. “The numbers are a guide, but it really depends on the population,” clarified Pink in a follow-up conversation about their findings. Even after completing the evaluation, they concluded that, “financial viability of this service delivery model is largely unknown.”

An Exception to the Rule

The FSED is one of several models that have been proposed to help rural communities affected by or at-risk of hospital closure. In a June 2016 report, the Medicare Payment Advisory Committee (MedPAC) proposed changing regulations and providing funding that would allow failing CAHs to convert to FSEDs. The report suggests providing fixed stipends or grants to cover standby costs and a potential requirement for the local community to provide matching funds.

Sedona has shown that the FSED can work in a rural community with the right mix of patient volume, outpatient services, and support from the community. In Streator, while the FSED is still very new, their chance to try the model required the flexibility and support of policymakers.

“You don't often see legislative activities custom-tailored to an individual community's response,” said Ryan Spain, Vice President of Governmental Affairs for OSF HealthCare. “But in this case, the General Assembly was willing to work on behalf of this one community, knowing that what happened in Streator may very well happen again and again in communities throughout Illinois and throughout the United States.”

We hope to be a footprint for the future of healthcare access for other rural communities…to keep the communities safe and provide them with quality access.

Both Spain and Beutke see the events surrounding the OSF Center for Health – Streator situation as unique. “We hope to be a footprint for the future of healthcare access for other rural communities…to keep the communities safe and provide them with quality access,” emphasized Beutke. “We think that will be a future impact – to be that pilot and future model.”