Sep 20, 2017

Confronting Adverse Childhood Experiences to Improve Rural Kids' Lifelong Health

by Jenn Lukens

When Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist Adrienne Coopey first arrived at Mission Health in Asheville, North Carolina, six years ago, the amount of trauma she was seeing in patients coming in from across the region was "mind-blowing."

"It was more than I had anticipated; it was intense. I don't think I realized how much child abuse there was in western North Carolina." Around that time, Coopey attended a presentation about adverse childhood experiences, otherwise known as "ACEs." She wasn't the only mental healthcare professional in the group who hadn't heard about the damage ACEs can cause to not only the emotional or mental health of a child but also their physical health later in life.

Coopey recalls the reaction in the room: "People were stunned. I was stunned. I said, 'We've got to do something!'" But the response she got from her colleagues wasn't nearly as enthusiastic, "because talking about child abuse is really hard," Coopey admitted.

What are Adverse Childhood Experiences?

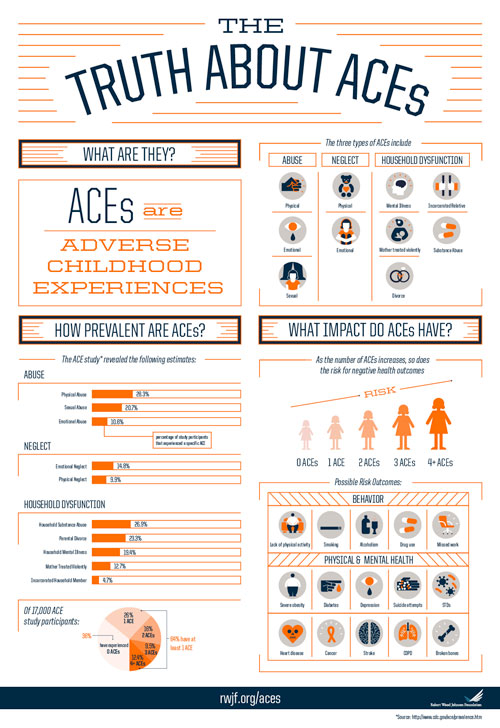

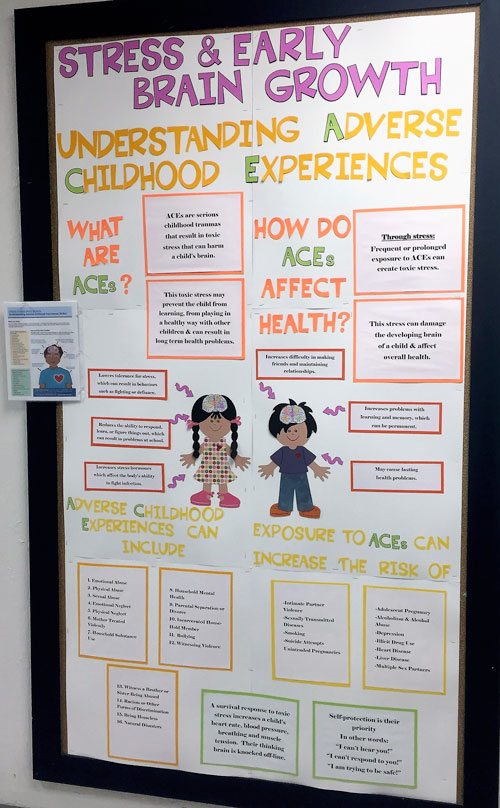

Adverse childhood experiences are significant disturbances in a child's life that affect their security and ability to function in healthy ways. ACEs include all forms of child abuse (emotional, physical, or sexual), neglect (physical or emotional), or household dysfunction (divorce, violence, incarceration, substance abuse, or mental illness).

The original 1998 CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study was the first to examine the link between ACEs and physical and mental health outcomes. Findings showed that the more ACEs a child experienced, the greater the risk of chronic health conditions, anxiety disorders, low life potential, and even early death.

Subsequent studies have backed the original ACE research and have found that, because the central nervous system closely interacts with the body's immune, hormone, and clotting systems, adverse experiences in a child's life, especially repeated ones, can change how the organ systems function later on. This process is known as "biological embedding" and could take years or even decades before symptoms start to show.

ACEs in Rural America

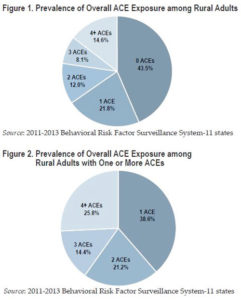

A 2015 HRSA report (no longer available online) found that rural children are more likely than urban children to experience certain kinds of adversity. This and other research prompted the Maine Rural Health Research Center to go a step further to find out how ACEs have affected rural and urban adults. Dr. Jean Talbot was lead researcher for the Center's Adverse Childhood Experiences in Rural and Urban Contexts study that was released in 2016.

Using the most recent available data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Assessment (BRFSS), Talbot and her team found that, while the prevalence of ACEs was comparable in rural and urban adults, over half of rural adults surveyed reported having ACE exposure. Among those with any ACE history, about one quarter experienced four or more ACEs.

The significance? "ACEs cluster together. People who report having an ACE are more likely to have more than one," explained Talbot. "It's easy to think of ways that this could happen. For example, if a parent experiences incarceration or mental illness, this in itself is an ACE for the children in the family, but it can also impair the adult's ability to care for kids. So it may open up the fault line exposing children to other types of adversity."

Talbot notes that their study's results have implications on the health status of rural America: "We know that ACEs are linked to high-risk health behaviors like smoking and alcohol abuse. These, in turn, contribute to health outcomes like heart disease, lung cancer, and diabetes – some of the major causes of the widening rural-urban mortality gap. So, if we want to close this gap, we may need to address rural ACEs as part of that effort."

The ACE Learning Collaborative

Around the time ACEs were introduced to Coopey, the ACE Learning Collaborative for Buncombe County was formed. Born out of a state-funded innovative approaches grant, it serves as a launching pad for the North Carolina county's many efforts to address ACEs.

Coopey is now a co-coordinator of the Collaborative. She views it as a support group of sorts for professionals who are working continually to address ACEs. "It's hard to do child psychiatry and trauma work all the time, so knowing that there is a bigger picture and that we are really having a greater effect on the community makes my day-to-day much more rewarding," she said.

The group is now made up of multiple primary care and mental healthcare agencies, community groups, and individuals who have helped Buncombe County become a trauma-informed community of practice. Institutions like the county jail and local law enforcement partner with the Family Justice Center – an intervention service for intimate partner violence, of which Buncombe County ranks one of the top counties in the state. Mountain Area Health Education Center (MAHEC) puts on a biennial ACE summit that attracts people from all over the nation. Buncombe County School District efforts, led by Director of Student Services David Thompson, are working at the ground level with students trying to stop the negative repercussions before they set in.

Compassionate Schools of Buncombe County

When he joined the ACE Learning Collaborative, Thompson knew trauma-informed care was what schools in his district really needed in order to address ACEs. With Buncombe County's wide socioeconomic spread, Thompson witnessed adverse childhood experiences on every level.

Buncombe County is part of the Appalachian region, covering a large geographical and cultural range. Within the school district, there are 71 languages spoken and 600 homeless students. Fifty-four percent of students are eligible for free or reduced lunches. Prior to 2014, there were not enough school counselors to go around, especially for the rural schools in his district.

"When you have a small school with a high need, you've got to be able to have a comprehensive supportive program. You can't say to a student, 'You can't see the counselor until they are back next Wednesday' when next Wednesday, they might need something else," said Thompson.

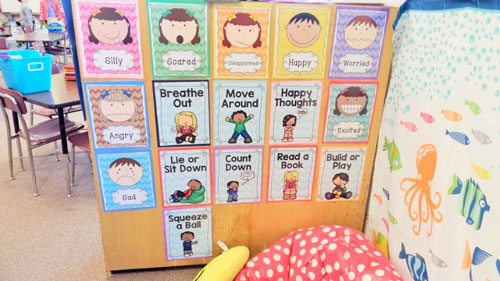

Thompson and his colleagues received the Elementary and Secondary School Counseling grant to hire more school counselors, fund trauma-informed strategies, and improve care coordination in Buncombe County schools. Out of the funds, they launched Compassionate Schools: The Heart of Learning and Teaching, a program that engages ten key principles to help students learn self-regulation, resiliency, executive functioning, and social/emotional competencies.

Prior to the start of the program, trauma was usually addressed only after it triggered an emergency room visit. Now, school's staff are trained to recognize signs of trauma in students and respond appropriately through their coordinated care system.

Because trauma is sometimes outside of a parent's or educator's ability to intervene, giving a child tools to change their thought or behavioral patterns when encountering trauma is a way to build resiliency, which Coopey defines as the ability to "bring yourself back to a baseline that helps you interact with the world around you." Thompson's work to implement resiliency principles is evident throughout the school and its students.

Each school has the option of integrating additional models like the Community Resiliency Model or Mindful Schools that teach quick methods to engage both mind and body. Classrooms set up "calm spots" that students can visit to "reset their brains." Teachers or students lead exercises like "rocket breathing" to regulate functioning. Students at Fairview Elementary demonstrate in this video:

The science behind each activity's effect on the brain is

taught to students in every grade. "We now have

kindergarteners that can tell you about their

amygdala," reported Thompson, who takes pride

in how even the smallest of students are using the

Compassionate Schools tools.

Coopey has witnessed the effect Compassionate Schools has on area youth and applauds Thompson's team. "The Compassionate Schools program couldn't be neater," she said. "It's something that will really affect a large population of people because it not only affects their children but also their families."

This video created by FrameWorks Institute, a nonprofit that specializes in social science analysis, explains how building resiliency can help people cope with ACEs.

Fostering Futures in Menominee Nation

Nearly one thousand miles away from Buncombe County is Menominee Nation, an American Indian tribe in Wisconsin with similar economic hardships. "If you choose to work or live in this community, you have to know its history," said Diane Hietpas. A non-Native, she moved to the reservation as a dental hygienist and has familiarized herself with some of the tribe's significant historical events that are still impacting today's generations.

Starting in the 1860s, Menominee children were removed from their homes and forced to attend boarding schools away from their tribe to learn Western culture. The boarding school environment often included abuse and neglect and, for many children, it was devoid of any love and affection.

One of the most recent traumatic events was the loss of federal recognition as a tribe in the 1950s, resulting in the depletion of jobs, closure of the tribal hospital, and a host of other problems. Both events were contributors to the intergenerational trauma that is still prevalent in Menominee Nation.

"Our people struggled during this period. Some of us were able to make it through with family support, and others had a hard time adjusting," said Jerry Waukau, administrator of the Menominee Tribal Clinic. After being reinstated as a tribe in 1973, the clinic and tribal leaders began looking at how to address some of the ramifications. "What we were finding is that a lot of people…were masking the pain: they were self-medicating, and they didn't like to talk about it," said Waukau. Substance abuse relapse and criminal recidivism rates were high and Menominee County outranked other Wisconsin counties in the number of child abuse and neglect cases.

We had been talking about historical trauma for ten years and the impact of poverty in our community. When we heard the message about trauma and the science of ACEs, it just made sense.

In 2011, the tribe was chosen to be a pilot site for Fostering Futures, a state-wide program that addresses ACEs and toxic stress using trauma-informed care, building resiliency, and reinstating hope in children. The Menominee Tribe asked Diane Hietpas, who was trained and experienced in conducting Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) for alcohol and other drug abuse, to help manage the new program from the Menominee Tribal Clinic. Hietpas worked as a provider for years in the clinic and had developed relationships with many of the families and patients. The SBIRT screenings grew to include depression and domestic violence; trauma screening seemed like a logical next step. "We had been talking about historical trauma for ten years and the impact of poverty in our community," said Hietpas. "When we heard the message about trauma and the science of ACEs, it just made sense."

The clinic started with educating parents: encouraging kindness, love, and positive tactics that add to a child's resiliency. Their next focus was the Menominee Indian School District, making resiliency a part of the everyday education system in hopes of stopping the cycle of intergenerational trauma. Then, they moved to the community, holding trainings to build trauma-informed care awareness at all levels in the tribe.

Much like Buncombe County's ACE Learning Collaborative, champions for Fostering Futures represent an array of organizations that work alongside the Menominee Tribal Clinic. Agencies that were once hesitant to get involved with helping youth have become some of the most engaged. "It's finally happened and we are expanding our partnerships within the community. We are now on a journey to improve the health of our community that will include cross-sector collaboration with a patient-centered care approach," said Waukau.

Treating ACEs: "The Doctor Will Question You Now"

While mental health practitioners are essential in the effort to treat ACEs, it's the primary care providers who often are the first responders to ACEs in rural communities. CDC's Essentials for Childhood Framework states that providers conducting well-child visits can capitalize on the opportunity to do something about them by talking with parents about the importance of healthy family relationships and practices.

ACE screenings also help determine a patient's ACE score, which can identify an increased risk of behavioral and physical health problems. Coopey is part of an ACE Learning Collaborative workgroup that educates primary care and mental health providers on the benefits of using the ACE questionnaire in their practices. The group has been pleasantly surprised by the number of medical providers who have agreed to give ACE screenings, but still receive some pushback. "It's hard because I think physicians are doers and they want a solution, but with ACEs, there's not necessarily one answer," explained Coopey. Although the ACE questionnaire gives a score based on the answers, there aren't set guidelines on how to treat patients based on their score.

Coopey advises providers to start with compassion, because a patient's noncompliance could be the result of a multitude of reasons the patient can't even put into words. "Understand that a person often isn't trying to be defiant or doesn't care about taking their medicine," said Coopey. "People's adverse experiences affect how they interact with medical care – their ability or desire to take their medications and do what they need to do to care for themselves."

Coopey also suggests that providers can learn from MAHEC's obstetrics program that uses motivational interviewing during prenatal visits to discuss how parental ACE scores could affect childrearing. "To be able to present it to someone in a non-judgmental way can be difficult, so this is a good way to do it."

You can't just give a stranger this ACE test and expect that everything's going to be fine. There has to be a good, trusting relationship there. People need to be ready to talk about it because it's very personal.

The Menominee Tribal Clinic will soon start ACE screenings and resiliency questionnaires for WIC families and obstetrics patients. Hietpas is training staff on how to preface ACE questionnaires with an explanation. She added, "You can't just give a stranger this ACE test and expect that everything's going to be fine. There has to be a good, trusting relationship there. People need to be ready to talk about it because it's very personal."

This is where rural providers have an advantage — because of their close-knit environments, many rural clinicians have already built those trusting relationships, making it easier to ask personal questions and receive an honest response.

Hope for Menominee and Buncombe County Youth

Hietpas and Waukau recognize that, with the amount of trauma and transgenerational trauma, progress to reach their goal of "no child in Menominee County ever having an ACE again" most likely won't be in their lifetime. But there is hope. "If we don't create hope for those kids, it becomes a hopeless situation, and then what? They're another statistic and they'll continue the same cycle their parents were in," said Waukau.

In the past, Menominee Nation has rallied behind efforts to reduce alcohol abuse and other harmful behaviors. With this new focus on ACEs and trauma-informed care, they are hoping for the same spirit. "Come back and talk to us in five, ten years, but for right now, we'll take those little wins – one family at a time. That's how we are going to build this change process," stated Waukau.

The question 'What is wrong with this child?' is being replaced with 'What has happened to this child?'

Buncombe County School District has learned many lessons through the implementation of Compassionate Schools. There are pockets of evidence proving their efforts are paying off. "Principals are saying, 'This makes a difference, more than anything we have ever done,'" relays Thompson. He has also seen a shift in the way teachers look at their students. The question "What is wrong with this child?" is being replaced with "What has happened to this child?"

As with any new initiative, there is still work to be done, but Thompson is encouraged by the potential this model has to launch healthy students into the world. "We want our students to be both college, career, and community-ready," he stated. "You are not going to ever be able to avoid problems in life, but how you are able to bounce back and respond is the key."

When working with children affected by ACEs, Coopey tries to identify with their needs, remembering that their experiences carry on into adulthood and, ultimately, form our future societies. Coopey reminds educators, medical providers, psychiatrists, and advocates of mental health of their significant role in a child's life: "There are plenty of people who have a high number of ACEs and are doing alright," she said. "Often, they had that one safe, stable, nurturing adult who was able to give them skills to cope in their situation and to support them."

Additional Resources

- Adverse Childhood Experiences: Informing Best Practices – Academy on Violence & Abuse

- Building Resilient Children by Creating Compassionate Schools – Video of presentation by David Thompson to the North Carolina Teachers' Convention, 2015

- Trauma-Informed Care Learning Communities – Best practices from the National Council for Behavioral Health

- Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) – Journal articles, BRFSS ACE data, and other ACE resources from the Centers for Diseases & Control and Prevention

- Menominee Nation: 2015 RWJF Culture of Health Prize – Article and video that tells the Menominee Nation story and how they are addressing ACEs

- Map of Adverse Childhood Experiences – Percent of children who had two or more ACEs from the National Survey of Children's Health

For further understanding of ACE's effect, watch this presentation How Childhood Trauma Affects Health Across a Lifetime given by Dr. Nadine Burke Harris on the TEDMED stage in 2014: